Canned designs: Tokyo's floating city

Today, when we think of an Asian powerhouse, it's China. Not so long ago though, it was Japan. In recent years – as discussed in these pages – it has been seen as the paradigm case of a nation coping with economic stagnation. But from the 1950s to well into the 1970s, the country was light years ahead of its competition: defeated in war, like Germany, yet it too was booming.

And no single architect did as much to shape the style, look and ethos of Japan's urban fabric during that heady period as Kenzō Tange. Like JG Ballard, Tange spent some of his childhood in Shanghai. But where Ballard saw man's inhumanity, the dystopias we accidentally create, the mess and gore and violence we seem sometimes to revel in, Tange saw the capacity for technology and a benevolent kind of progress with which to build fantastical new cities straight from the pages of comic books.

He used tropes from Japan's past to ameliorate the radicalism of his designs – joints that you see in temples, that kind of thing. But he really ripped up the rule book otherwise. His Yoyogi National Gym for the Tokyo 1964 Olympics was a structural triumph: a suspension bridge designed as a gym, a roof supported like a road would be over a river. Working in raw concrete, his madly abstracted buildings like the Yamanashi Press and Broadcasting Centre became emblems of the brutalist movement – complete flights of fancy.

Tange saw a capacity for technology and a benevolent kind of progress with which to build fantastical new cities straight from the pages of comic books

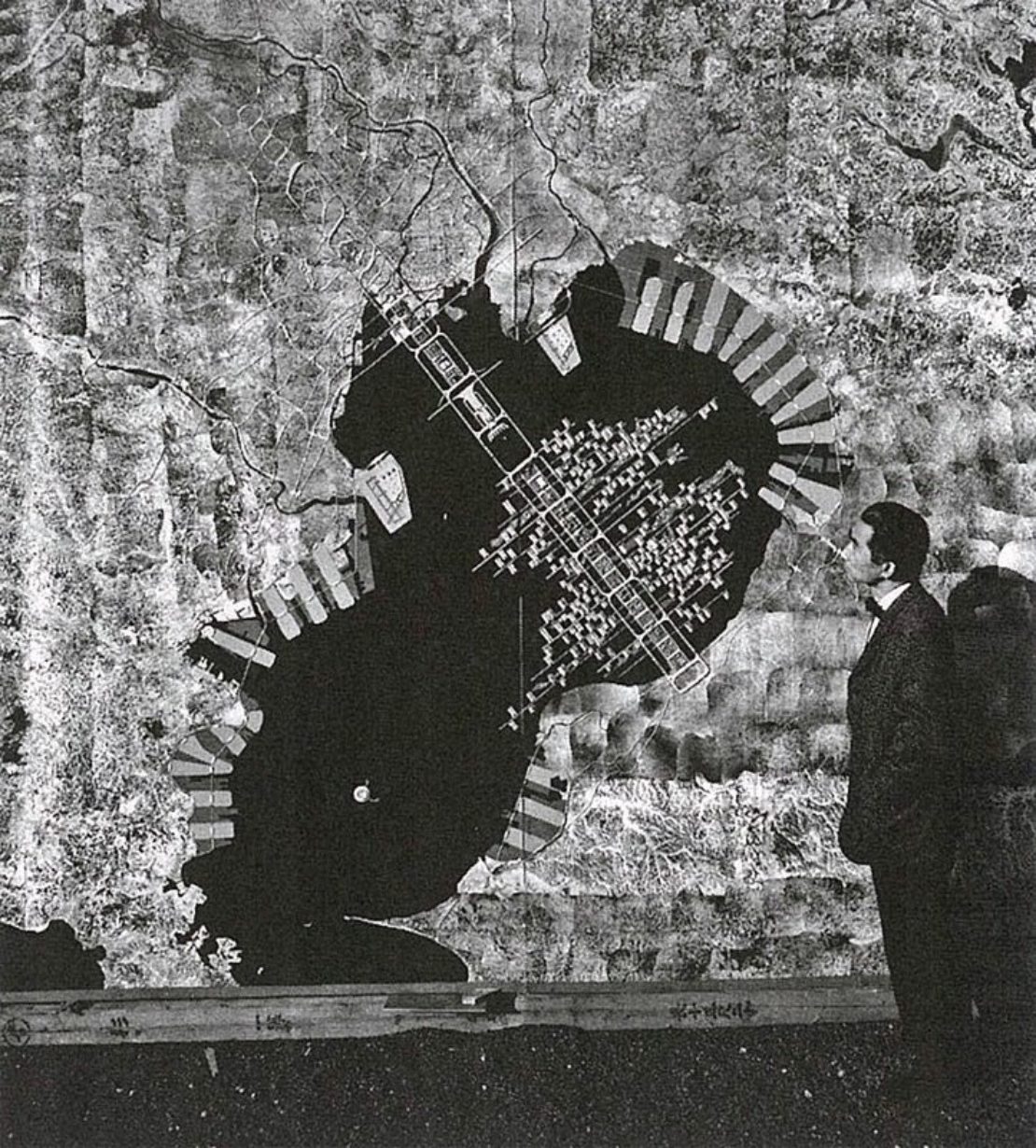

But Tange was rigorous and his ideas came from deep thought and scientific study. With his 1960 Tokyo Bay Plan he envisaged Tokyo expanding into its bay. From prêt-à-porter to pâtisserie, Tokyo is obsessed with Paris, and there's something very French, very Haussmannian about the grand axis Tange wanted to feed across the bay: like a Champs-Élysées surrounded by water. Each side of the axis (comprising freeways and services) would be platforms like oil rigs on which would sit crazy combinations of buildings stacked up and plugged in to each other. The project, er, sank, eventually – but its legacy never went away, especially down the coast in Osaka.

When Osaka was building its new airport 30 years later it created an artificial island and strung a straight causeway out to it. All very Tange. And 10 years after the Tokyo Bay Plan, Japan's final and biggest moment in the spotlight was the Expo at Osaka 1970, the event at which many commentators like Douglas Murphy contend modernism died. This was the last time we dreamed big. And the plan for Osaka 70? It was by Tange, of course. The megastructures and the grand axes were lifted straight from his earlier Tokyo Bay Plan.

Tange worked well into his nineties and produced edifices like the huge Tokyo City Government Building close to his death. But it's for his capsules and his plug-in buildings, his megastructures and his unbuilt ideas that he'll always be known. He catapulted Japan into the future. But he could have taken it even further.