Inner city life

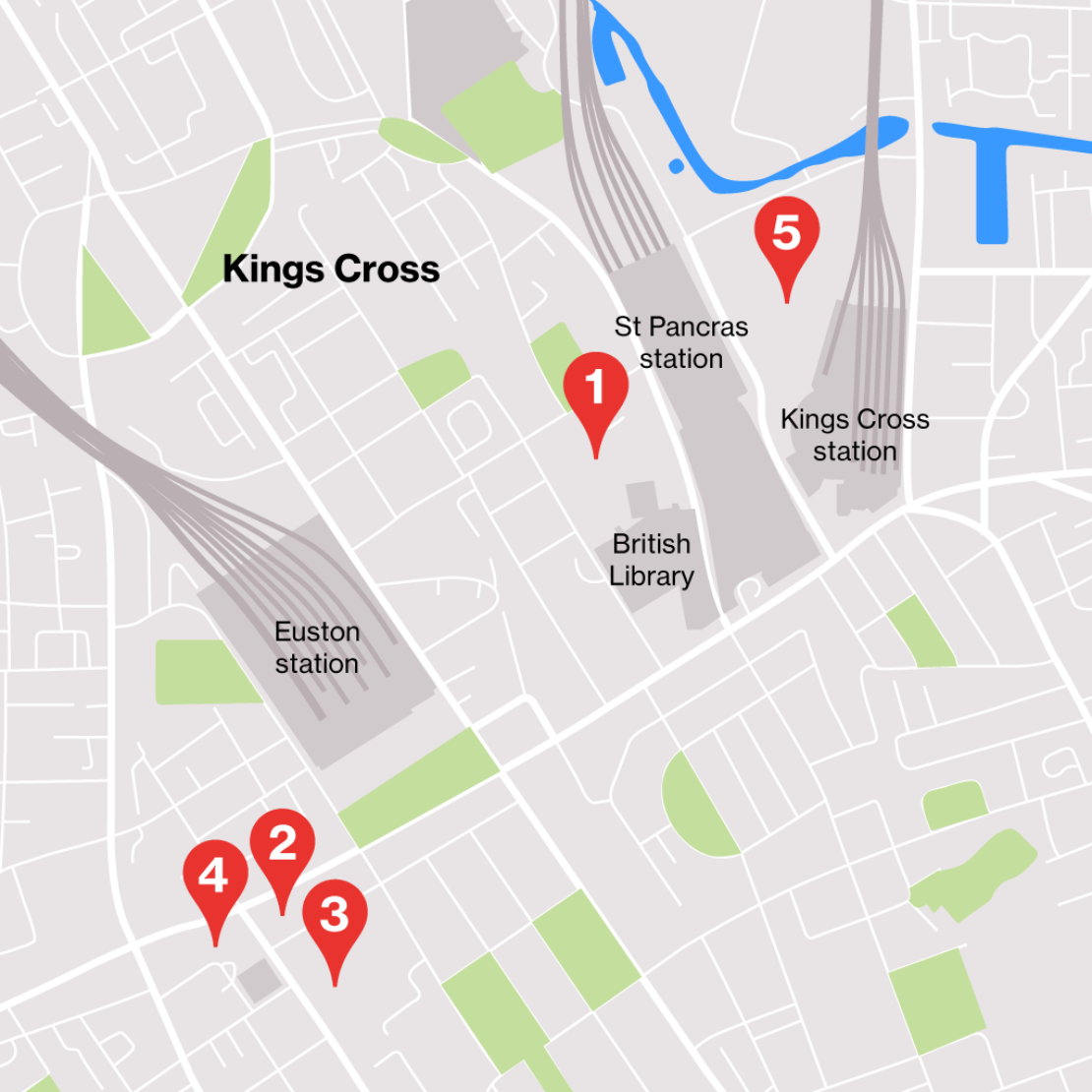

In a portacabin next to a massive building site behind the British Library, screens, illustrations and texts line the walls. They outline a grand vision for what is being built beside them. In the middle of this humble setting sit two glass boxes containing intricate models of what will become the largest centre of biomedical research in Europe. This is the Francis Crick Institute, referred to by all and sundry as The Crick and currently rising up into the St Pancras sky.

First mooted as an idea over a decade ago, the Crick was launched in 2007 under Gordon Brown’s Labour government and is taking shape in the centre of a redeveloped, newly upmarket King's Cross, which now also houses Central Saint Martins and The Guardian, with Google due to build their expansive new UK HQ in the area too. London’s mayor, Boris Johnson, sees the institute as a cornerstone of his MedCity scheme, which intends to “position London and the greater south east of England as a world-leading, interconnected region” for life sciences. The Crick is also within walking distance of two of its funders, the Wellcome Trust and the Medical Research Council.

The institute is backed by some big hitters: Boris Johnson says it will “keep London and the UK at the forefront of the battle to understand health and disease, and further anchor the capital as a world leader in scientific research.” The mayor hopes that, as David Willetts put it when he was minister for universities and science, it will be “the jewel in the crown of UK medical research”. David Cameron predicts that many “startling discoveries” will be associated with the Crick in the years to come. George Osborne is a keen supporter and has donned his hard hat for a tour of the building site.

But with the UK’s overall science budget pegged, the cost of living in London rising sharply while the rest of the country struggles and misgivings over a project that might be viewed as too big to fail, the Crick is also attracting criticism and causing concern. As Kim Nasmyth, Whitley Professor of Biochemistry at Trinity College Oxford, told me: "There's a great deal of anxiety that they're building a huge, Titanic-like structure at a time when the science budget is being tightened.”

Construction on the institute will be completed next year. Research there will “address questions relevant to a wide range of human illnesses including cancer, cardiovascular disease, infectious disease, autoimmunity and disorders of brain and behaviour.” By July 2016, it will be fully operational and by 2018 or 2019 it is expected to be at full capacity, with between 1,500 and 1,600 people working under its artfully vaulted roof. There will be over 1,000 researchers working in about 120 groups spread over four floors and four laboratory wings.

These scientists will be led by the lab’s director, Nobel laureate and president of the Royal Society Sir Paul Nurse, and joined by support staff and an “entrepreneur in residence”, currently Howard Marriage, who has worked in the biotech industry since the early 70s. Sir Paul is a widely acclaimed geneticist and a grand man of the establishment with an impressive track record of running big institutions. He was awarded a Nobel Prize in 2001 for his work on the role of DNA in cell division and in 2003 he was named president of Rockefeller University in New York. In 2010 he became the president of the Royal Society and his appointment at the Crick was announced.

In some senses, it seems as though the lab Sir Paul will direct will, in fact, be a simple relocating of two storied institutions. Initially, most of the researchers at the Crick will come from the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR), which is leaving its gothic HQ in Mill Hill, north London; and the London Research Institute of Cancer Research UK, which is saying goodbye to its site at Lincoln’s Inn. The Crick’s first PhD programme has just been launched. There were 1,300 applications for 46 places.

These big numbers reflect the scale of ambition in place here. In a country not known for its affinity withgrands projets, the Crick is exactly that: a grand project funded by the British government through the Medical Research Council (MRC), with a little help from Cancer Research UK (CRUK) and the Wellcome Trust. The Crick also has a partnership with University College London, King’s College London and Imperial College London, all of which will have staff working at the lab when it is completed.

The building of the lab is set to come in at around £650m. The MRC has provided £300m, CRUK £160m, the Wellcome Trust £120m and the London universities £40m each. The operating budget will be over £100m a year, and while it is thought that £40m of that will come from CRUK, specific details have not yet been revealed.

A Crick spokesperson told me that this heavyweight collection of partners “represents an unprecedented joining of forces to tackle major scientific problems and generate solutions to the emerging health challenges of the 21st century.” Staff from UCL, King’s and Imperial will remain employed by those universities. The rest of the lab will be employed by the Crick: how it will work with unions is “currently under discussion”, a spokesperson said.

The Crick’s overarching aim is to “discover the basic biology underlying human health, improving the treatment, diagnosis and prevention of disease and generating economic opportunities for the UK.” Connected to this are the institute’s five strategic priorities. According to its 80-page strategy document, it intends to, “pursue discovery without boundaries”, “create future science leaders”, “collaborate creatively to advance UK science and innovation”, accelerate translation for health and wealth” and “engage and inspire the public”.

The institute believes that, in Britain, new drugs are currently taking too long to go from the bench to the bedside. Translational medicine is a key focus of the Crick’s, and Sir Paul Nurse has talked about his hope that the pharmaceutical industry, the NHS and research scientists can work more closely together in order to make brave new ideas become brave new realities faster. “We are attempting to re-examine the way scientific research is conducted by working in a more open, collaborative way,” a Crick spokesperson told me. “The generation of scientific ideas and their translation into health and economic benefits is a continuing process of innovation.” The recent hiring of former Pfizer executive David Roblin as chief operating officer and director of translation shows the Crick’s eagerness to engage with the wider world and to work with the pharmaceutical industry.

On my tour of the building site’s adjunct buildings and during my conversations with various employees of the Crick, the idea of “permeability” and the freedom of different researchers to work with each other cropped up again and again. A cornerstone of the innovation the lab hopes to generate lies in the architecture of the site. Scientists will be drawn together in light-filled atriums on the centre of each floor and at facilities available to the whole institute on the ground floor. There will be a canteen to encourage the staff to eat together. Early in the design process, the local council had tried to insist that there be no canteen so that the staff would go out and use the local shops. This was a deal-breaker. The canteen stayed. Researchers needed to be able to eat with each other in order to share innovative ideas.

The hope is that scientists from different areas will inspire each other at the water cooler. “Compared to many other labs we hope the Crick will feel more open and permeable to all types of researchers and also to the public… Increased interactions between Crick biologists and physical and clinical scientists at the university partners will pay dividends to both sides,” the Crick spokesperson told me.

Speaking to me on behalf of the N8 Research Partnership – an organisation of eight of the research intensive universities in the north of England – Paul Stewart, dean and professor of medicine at the University of Leeds, said that he believed this collaboration would go beyond the airy corridors of the Crick and out into the UK’s research landscape as a whole. “The opportunities for enhanced collaboration across institutions and fostering multidisciplinary research across the medical-physical sciences interface are significant and are welcomed by the N8 universities,” he said. “The ability of emerging scientists and clinicians in training to engage with and rotate through the Crick is currently being explored by N8 partners.”

The idea that lots of scientists in a large building will rap with each other and come up with a stream of great new ideas is being met with some scepticism. “The Crick believes, with no evidence either way, that you can create big glass boxes and atriums and that scientists will meet and bounce ideas off each other,” says Kieron Flanagan, a senior lecturer in science and technology policy at Manchester Business School. “There is a lot of evidence that small groups are more productive than larger ones. The Crick is big, inflexible and has longterm funding commitments. The Research Council can’t afford to let it fail.”

Kim Nasmyth agrees with him. “Small is beautiful in these matters… Science has to run on the basis of being able to shut down if it doesn't work. The longterm problem with the Crick is: What do you do if it doesn't work? Sink more money into it?" Nasmyth points to the Cancer Research’s Clare Hall Laboratories at South Mimms in Hertfordshire as an example of his “small is beautiful” theory. It is, he says, “possibly the best molecular biology institute in England besides the MRC laboratory of molecular biology in Cambridge. It’s a small unit and the thing that made it work was the person who ran it. Now it's being shut down and moved to the Crick.”

The advantage of small labs like the one at South Mimms is that if, for whatever reason, they don’t work they can easily be shut down. This is something that seems to have been recognised in corporate research and development. The golden era of massive corporate labs – as exemplified by the Bell or Xerox Parc labs – is long-gone, while Pfizer recently shut down its plant in Sandwich, Kent. The big, out-of-town science parks are being replaced by biotech startups. When I brought up this trend, a Crick spokesperson said: “In terms of the number of research groups it is about the size of a large university department. Research groups within the institute will be relatively small.”

The person in question, John Diffley, who runs Clare Hall Laboratories in South Mimms and who will be moving to the Crick, is philosophical about the situation. “I’m sad and excited in equal measure,” he tells me. He agrees with Nasmyth over the benefits of remaining small, but says that often, mediocre set-ups can fly under the radar and thus continue to drain resources. The high profile of the Crick will, he hopes, push it to rise to the challenge. Rather than being too big to fail, it will be too big not to inspire those in it to make it work.

Diffley also helps to turn the official Crick line on “permeability” into something a little more concrete. At South Mimms, he has eight groups of scientists working on issues that relate to one another; but he doesn’t have anyone designing new technology or doing something new in a field a little further removed from his.

He is excited by the access to new technology that the Crick will give his team: “Science is driven by ideas. And that’s why Clare Hall has been good because we have common ideas about things. But it’s also driven by technology, more and more… There is a benefit to being around people who are using different technologies and it is also difficult, in a small place, to maintain cutting-edge technology. A bigger place allows you to do that.”

That’s because new machines get invented that do new things. Those machines are invariably, in their first incarnations, rather large. Over time, they get smaller but as they are getting smaller, new machines that do new things – or the same things, but better – are getting invented, and those machines are big. As Diffley points out, “Breakthroughs in imaging technology mean that microscopes are getting better.” So having a vast building in King’s Cross to house them might not be such a bad idea.

Still, the danger that this laboratory could turn into a lumbering mistake conjured up more out of vanity than practicality, remains. A government can get behind a lab like the Crick because it looks like an investment in the future, because no one is against these projects, because the hard hat photo opportunities are terrific and because, compared to other infrastructure projects like roads or railways, big science and technology institutions really don’t cost that much and the money for them can come out of the ongoing science budget.

The £650m spent on the Crick’s construction equates to about eight miles of high-speed rail link, which puts the Crick in an odd double bind: it could be an expensive problem to the life science community while also speaking to a certain lack of commitment on the behalf of government. George Osborne says he intends to keep the country's research and development budget at its current level through to the next election. This figure, which amounts to about £4.6bn per year, has been held flat since 2011.

Dreamed up in the days before the credit crunch and before the rise in house prices in London reached crisis-point, questions have been asked about where exactly the Crick’s staff will live and how they will afford to live the life of the dashing young scientist. Post-doctorate positions usually pay between £27,000 and £30,000 a year in a university or research institute, depending on location. Jobs in the sector obtained following a master’s degree normally pay between £17,000 and £21,000 a year.

The Rockefeller University in New York, where Sir Paul Nurse was president from 2003-2011 and on which the Crick is partly modelled, provides subsidised housing for its workers. Biopolis, the international research and development centre in Singapore, is linked to a large development which offers accommodation for employees. There were calls in the early stages of the Crick’s development for part of its budget to be sunk into property for the staff. Those calls went unheeded. Today, the Crick acknowledges that cost of living has been a “concern since day one”, but believes that all the exciting glories London has to offer more than make up for any concern about how far an employee’s commute might end up being.

For the initial staff intake, though, questions about the cost of living are largely irrelevant. These researchers will be moving from institutions already in London. For those yet to be employed there is a concern, often articulated by Sir Paul, that the government’s current anti-foreigner rhetoric will be more of a deterrent. The Crick is hoping to recruit from abroad and doesn’t want that process to be complicated by government policy. It takes a “best scientific athlete” approach, which sees appointments being made “based on a joint consideration of the quality of the candidate and his or her research programme”.

The Crick, then, will be a home for the best and brightest, one that symbolises London’s dominance at home and, perhaps, abroad. According to Kieron Flanagan, Sir Paul Nurse has said this institution could only be in London, not the “provinces”, a suggestion he found “patronising and politically inept”. Sir Paul is a powerful figure and few people are willing to question him publicly but there are plenty of others like Flanagan who see the establishment of a large lab in a city that already hoovers up talent as being detrimental to the rest of the country. In June 2014, George Osborne, speaking in Manchester, said:

“What’s the Crick of the north going to be? Materials science? Nuclear technology? Something else? You tell me. Today I call on the northern universities to rise to the challenge, and come up with radical, transformative longterm ideas for doing even more outstanding science in the north – and we will back you.”

But why should there be a Crick of the north when the Crick is meant to serve the whole of the UK? And how can this Crick of the north come about when such institutions are invariably situated in London, the centre of power and money? As Andy Westwood, CEO of the higher education body GuildHE, told me in relation to the regional skewing in the UK’s science budget, “Whilst the imbalance is not as dramatic as in overall local spending, there is still a widespread view that much science investment and spending is concentrated in the golden triangle,” which is made up of Oxford, Cambridge and the London universities.

The Crick's plans to break down the walls between different scientific disciplines, to engage with its local community, to provide young scientists with a start in life (contracts are six years long, with the option of a further six years, before the employee is encouraged to leave for other institutions), and to work with the NHS are all noble and could all bear fruit. “If it sounds a bit like anarchy, that is because it will be a bit like anarchy,” Sir Paul Nurse has said. But while he may be in love with the idea of free-range scientists roaming around his great palace of light and learning, freely sharing ideas with each other like a group of improvising musicians, the reality is another large institution based in London that could become a problem simply because it is too big to fail.

There was a time when a big scientific project like the Crick would be welcomed without reservation. Now, questions are being asked. As Kim Nasmyth says, "I hope it works; because if it doesn't we're all in trouble."