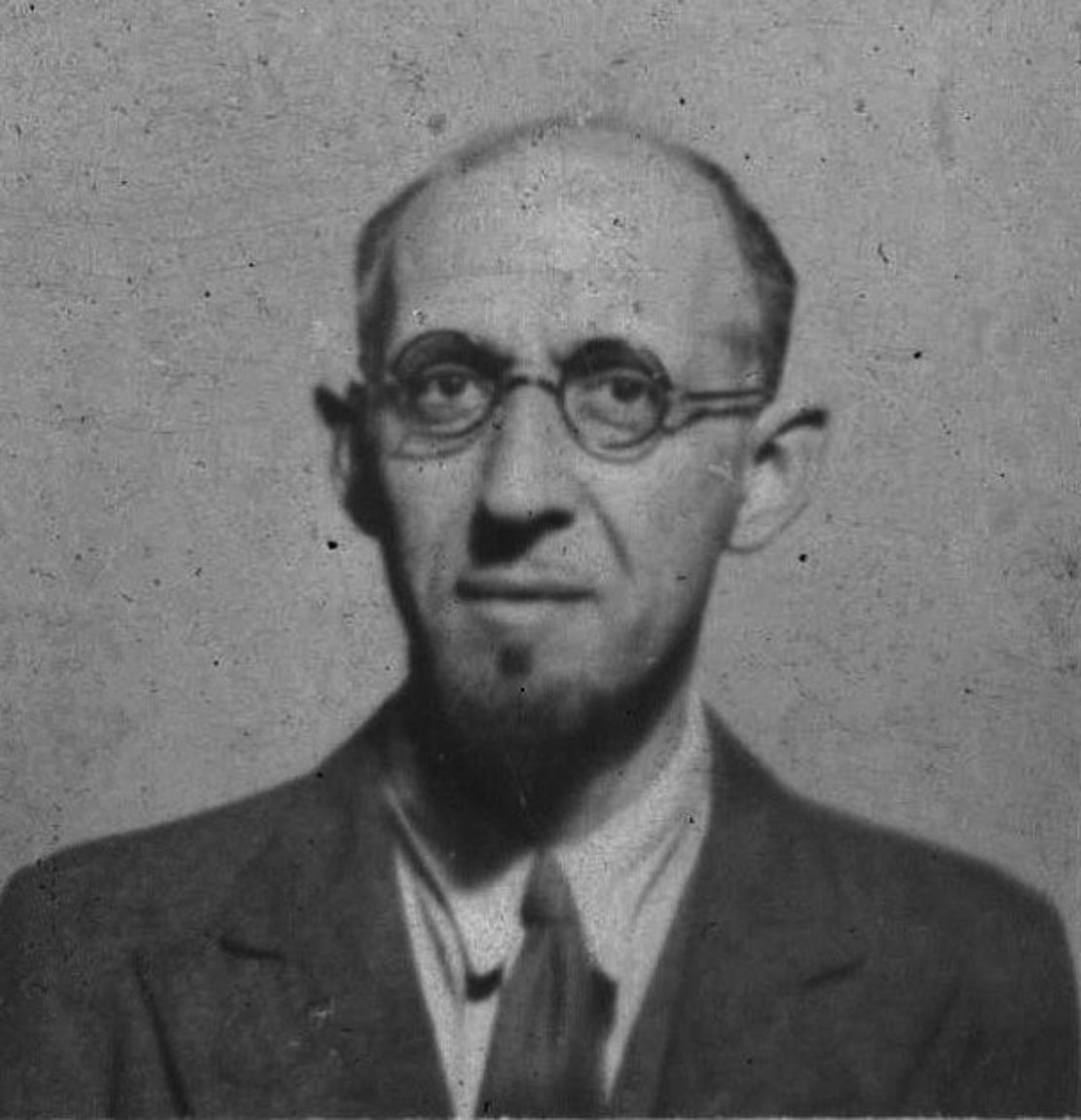

Innovation heroes, #3: Geoffrey Pyke

Who?

Pyke was first a journalist, having landed a job as a foreign correspondent at the age of 20 after sneaking into wartime Germany under a false passport in 1914. But he became better known in his later capacity as an inventor – particularly for his unorthodox weapons of war. In WWII, Pyke was enlisted by the British War Office into Combined Operations HQ, where it was his idea, in late 1942, to construct aircraft carriers out of giant icebergs.

Bergships

Britain needed something to take on the U-boats in the mid-Atlantic, which were beyond the reach of land-based planes. Steel and aluminium were in short supply. Ice could be used on the cheap, reasoned Pyke: level off and hollow out an iceberg and maybe it will yield a decent carrier. Winston Churchill liked the idea, and Britain ran with it for a bit, under the codename 'Project Habakkuk', alluding to its audacity by referencing the Book of Habakkuk, I:5: "Be astonished! Be astounded! For a work is being done in your days that you would not believe if you were told."

Pykrete

Trouble was, they couldn't find any icebergs big enough. Pyke's eventual breakthrough was a new material, a mixture of wood pulp and ice that was strong, slower to melt and could be cut and cast into shapes. He called it 'pykrete'. Experiments on its viability were secretly conducted under London's Smithfield market, in a meat locker behind frozen animal carcasses. A small prototype 'bergship' was then built on a remote lake in Alberta, Canada, over the summer of 1943.

Thawed dreams

After many months of testing, however, it became clear that the structure had a tendency to melt and sag. A bergship was deemed too difficult to build, requiring more resources than originally thought. In fact the amount of steel needed to freeze a ship was more than would be needed to build a new carrier of pure steel.

Ultimately, the increasing range of aircraft rendered such carriers unnecessary anyway. Pyke was axed from his own project. In protest, he messaged Lord Mountbatten, his boss, with a cable that read (in full): "CHIEF OF NAVAL CONSTRUCTION IS AN OLD WOMAN. SIGNED PYKE."

Backstory

Pyke, like Pykrete, has largely been forgotten since. At the end of his life, depressed, he said he would be glad to go unremembered. But a new book by Henry Hemming revives and celebrates Pyke's story, and tells many more tales of his eccentric character and verve for invention. It describes how he changed the landscape of preschool education in the UK by building a radical school of his own, mostly for the sake of his son, and financed his folly by riding futures markets and arbitraging the relative prices of tin and copper. At one point he controlled a quarter of Britain's tin reserves, until it bankrupted him.

Afterward

After the war, Pyke continued to invent, his ideas often rooted in a cool, plain logic. One idea was for human-powered railways, driven by a couple of dozen men pedalling a 'cyclo-tractor', reasoning that there was a shortage of coal but no shortage of the unemployed. Ultimately he grew pessimistic about the world's ability to welcome his ideas, was widely mocked, and took his own life. Hemming's book suggests, based on records released in 2009, that Pyke was a Soviet spy – and MI5 had helped put an end to his career.

Upon his death The Times called him "one of the most original if unrecognised figures of the present century".