Fair re-use?

On 1 September, newly appointed culture minister Sajid Javid made his first speech to the British music industry. It marked a truce between the music industry and the government, following a battle in which the UK’s creative industries had fought head-to-head with the world’s tech giants over reforming Britain's copyright laws.

“[The] digital age has created new threats for copyright holders around the world,” Javid told delegates at the British Phonographic Industry's AGM. “[In] just one quarter of last year almost 200m music tracks were consumed illegally… No industry and no Government – can let this level of infringement continue on such a massive, industrial scale… Copyright infringement is theft, pure and simple.

Turn back to four years ago, shortly after Cameron’s election, and the Government’s rhetoric on copyright was very different. “The founders of Google have said they could never have started their company in Britain,” the Prime Minister told an audience of entrepreneurs in November 2010. “The service they provide depends on taking a snapshot of all the content on the internet at any one time and they feel our copyright system is not as friendly to this sort of innovation as it is in the United States.”

The announcement that followed threw a grenade into Britainʼs creative industries, starting with music, which had been the first to be hit by online piracy: there would be a major review of the UKʼs intellectual property and copyright laws. While this was greeted with cheers by the likes of Google and other tech giants, the Government’s bid to relax the laws on paying for the content the music industry’s whole business model depended on was a shocking move. Cameronʼs proposal was clear – he was asking the creative industries to take a financial hit to allow the tech companies to flourish. But as he would soon find out, it would not be met without a fight.

The case for reforming copyright law: Hargreaves

Professor Ian Hargreaves Review of Intellectual Property and Growth was published in 2011. It made 10 major recommendations to free up Britainʼs intellectual property and copyright laws, which he claimed were archaic, restrictive and a barrier to economic growth.

“Could it be true that laws designed more than three centuries ago, with the express purpose of creating economic incentives for innovation by protecting creatorsʼ rights, are today obstructing innovation and economic growth?” he wrote. “The short answer is: yes.”

The recommendations impacted on publishers, designers, film companies, scientific researchers and every bedroom whizzkid who wanted to post a YouTube mash-up. His suggestions included making it easy to license music online with a one-stop shop for digital rights clearance; lifting restrictions on parodying copyrighted material (a case highlighted by the takedown notice served on Newport State of Mind, a British parody of Jay Z and Alicia Keys’ 2009 song Empire State of Mind); and allowing the free use of works where an owner is unknown. In particular, he highlighted the need to change the law that made it illegal for music fans to download a purchased CD on to an MP3 player – a move he claimed would alone bring an extra £2bn of growth to the UK economy.

But the subtext of Hargreavesʼ report went much deeper. Music industry lobbyists, he said, had commanded too much power over copyright law for too long. “There is no doubt that the persuasive powers of celebrities and important UK creative companies have distorted policy outcomes,” he claimed.

(Disclosure: In 2013, Ian Hargreaves co-authored a report called A Manifesto for the Creative Economy, which was released by Nesta, the publisher of The Long + Short.)

The case against reforming copyright law

As influential members of the music industry were quick to point out, if by relaxing copyright laws the Government took away its right to make money, investment in new talent would suffer. And it had strong economic and cultural levers to win politicians over. As major record label EMI argued in its response to Hargreavesʼ proposals, weaker copyright law would have a ‘chilling effect’ on investment in new artists. “[It] will not provide the environment in which the UK can maximise the opportunities to continue innovating and creating the cultural and economic phenomena of the future who would follow the path first trodden by the Beatles or the Rolling Stones,” its response read.

Many also objected to the growth projections forecast by Hargreaves, which lobby group UK Music claimed were “unreliable at best and plain wrong at worst.” Furthermore, Hargreavesʼ premise that copyright is an inhibitor to growth, “unnecessarily and incorrectly puts the growth of the digital technology sector in direct conflict with the creative content sector.” The calculations were also later rejected in a report, published in 2013, by MPs on the Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee.

What about Google?

For many in the music industry, the view that British copyright law was broken and needed fixing was driven by the Conservativesʼ close links with the tech industry. “Some people referred to the speech that Cameron did to launch [Hargreaves] as the ‘Googlesburg address’, as a joking reference to the Gettysburg address,” says Tom Kiehl, director of government and public affairs at UK Music. “There was a sense that a lot of things were driven by the tech sector and high players within that field and obviously you would include Google as part of that.”

Scott Walker, director of government relations at the PRS (Performing Rights Society) for Music, agrees. “There has been a concern in the creative industries that the technology companies are taking advantage in some respect. They have the most to benefit from these changes at the expense of the creative industries.”

Cameron’s senior policy adviser at the time, Steve Hilton, was seen by many as one of the key drivers of the copyright reform agenda. He is also married to Rachel Whetstone, Googleʼs vice president of communications, and has been a close friend of Cameronʼs since they worked together at Carlton Television in the 90s.

Revelations shortly after the announcement of the copyright overhaul that coalition ministers had met with Google representatives at least once a month since gaining office, followed by the publication of photos of the Camerons at the wedding of former Tory adviser Naomi Gummer, who went on to a job as a senior executive at Google, did little to stifle the view that the tech giant had access to decision makers at the highest level.

Old media has money for lobbyists; new media has money for growth

Giving evidence to the Culture, Media and Sport Committee inquiry on the creative economy and copyright reform, the Governmentʼs own intellectual property minister Lord Younger revealed that the company had a higher reach than him. “Google is one of several search engines. I am very aware of their power, put it that way,” he said. “I am also very aware, I think, that they have access, for whatever reason, to higher levels than me in Number 10.”

“[Hargreaves’] report had long become known as the Google report,” Labour MP Paul Farrelly, one of the committee members, says. “When we questioned Professor Hargreaves, the so-called benefits from relaxing copyright exceptions simply disappeared into thin air… The suspicions were always that this was a task set for Hargreaves that would only benefit Google and (typically US) internet giants, who want to chip away at the protections of copyright which are the fundamental basis for success in the creative industries that are so important in the UK.” That, he says, together with the companyʼs well-publicised tax avoidance schemes and seeming reluctance to deal with online piracy, only reinforced antipathy towards them from the creative sector.

“Five or six years ago most of the tech companies were terrible at lobbying,” says Jim Killock, executive director of the digital rights campaign group Open Rights. “Then, when big threats started coming up like copyright, pornography, and privacy issues, Google had to learn how to deal with the government. In the last four years theyʼve really put in the effort and employed people to do this. I donʼt think you can accuse them of being exceptional lobbyists though, their reputation is still dismal.”

Google have drawn from both sides of the political spectrum to form their new lobbying and communications arm. Recent Labour-affiliated recruits include Theo Bertram, a former special adviser to Tony Blair and Gordon Brown , and Tom Price, former aide to Douglas Alexander. DJ Collins, a Labour adviser and close friend of David Miliband, also held a senior policy and communications post before leaving in 2012.

Despite this, most MPs still say they have had very little contact with Google. “But if you are a company that size, you donʼt need to rally MPs,” says former Labour party technology tsar Kerry McCarthy MP. “Why would you bother if you already have a way in to Number 10 and the Treasury?”

Google declined to comment for this article and directed questions on the subject to their published statement on copyright.

How powerful is the music industry lobby?

As Will Page, director of economics at streaming service Spotify, puts it: “Old media has money for lobbyists; new media has money for growth.”

And while it appeared that Google were making progress with the new Cameron government, the music industry has a long history of pushing for copyright laws that benefit rights holders. In a world where one in eight albums sold globally is by a British artist, the UKʼs music industry is a strong voice, both culturally and economically. It employs over quarter of a million people.

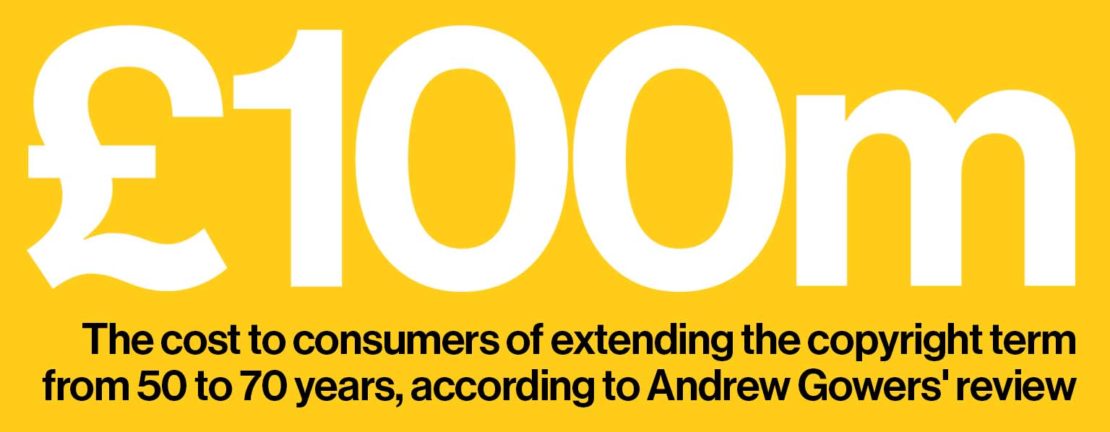

At the end of 2005, the then chancellor Gordon Brown commissioned Andrew Gowers, former editor of the Financial Times, to lead an independent review of intellectual property rights. He found that extending the term of copyright from 50 to 70 years, in accordance with a proposed EU ruling, would cost consumers £100m during the extended term and would bring little benefit to the creative economy – particularly struggling musicians. The Government agreed.`

“There was a very gentle lobby for a long time,” says Jon Webster, founder of the Mercury Music Prize and CEO of the influential trade body Music Managers Forum, which receives funding from Google and other tech companies, as well as record labels and rights owners. “But when [our] national treasures the Beatles were going out of copyright, that galvanised the fight.”

“No musician thinks, ‘I only have copyright until 2064, I must be able to get paid until 2084 or I’m not going to make this,’ says Jim Killock of Open Rights. “But the industry pushed for it, so they could continue to make a profit from the Beatles and Rolling Stonesʼ recordings.”

The announcement came when the then culture secretary Andy Burnham met with Undertones frontman Feargal Sharkey, the then UK Music boss. “The Culture Secretary met his childhood hero and immediately after that the government changed their position on copyright,” says Killock.

Gowers accused Burnham of being “silly” and “star-struck”, and of “lining the pockets of lobbyists from the When Iʼm Sixty-Four generation,” instead of supporting new talent. Burnham did not respond to the criticism.

But as the last general election drew closer, it was business secretary Peter Mandelsonʼs relationship with big players in the music industry that came under scrutiny, after his surprise decision to include controversial anti-piracy laws in the Digital Economy Act 2010. Measures such as cutting off internet access to people who illegally downloaded material were not enforced; indeed, they had been deemed unworkable in the Governmentʼs own Digital Britain policy paper. There were rumours that Mandelson had been swayed after dining with record label boss David Geffen at a Corfu holiday villa, though this was denied by Mandelson. Letters obtained under the Freedom of Information Act later revealed that Mandelson had advised on tougher piracy measures to be included in the draft bill the day after a meeting with Lucian Grainge, the chairman of Universal Music.

Was the then business secretary influenced by powerful figures within the music industry? Labour MP Tom Watson thinks so. “If youʼre looking at the last couple of years in the Gordon Brown government, the most important relationship was Peter Mandelsonʼs with Universal,” he says. “His personal relationship with senior executives there was the key thing. Almost nothing else mattered.”

Labour simply couldnʼt afford a battle with the music industry in the run-up to the general election, he says: “There were elements within the music industry, some of the big publishers, whose lobby strategy was, ʻIf you donʼt slow up on modernising the legal framework of copyright laws, weʼll choke off your celebrity parties and celebrity endorsements. If you want to go into a general election and have your politicians seen with bands, you have to play the game with us. It was as naked as that.”

Sajid Javidʼs speech earlier this month marked what the music industry has seen as a considerable mood shift in the copyright reform agenda since Cameronʼs 2010 ʻGooglesburg’ speech. John Mottram, public affairs manager at PRS for Music says,

“Hargreaves was the pinnacle of the intensive reform agenda. What weʼve seen since has actually been the slowing and relaxing of that intense pressure from the governmentʼs point of view.”

Mike Weatherley MP, former finance director at Pete Waterman Group and now adviser to David Cameron on intellectual property, says: “When I got into parliament in 2010 it struck me that the government was just giving away intellectual property rights. We still get arguments from those who think copyright should be a free-for-all, but in the last three or four years weʼve turned that juggernaut around, and now people are saying it is worth protecting and this is something we should do.”

Richard Hooper was appointed to conduct a report into the feasibility of creating Hargreavesʼ proposed one-stop shop for online copyright licensing, to make it easier for people to pay to use copyrighted material. He agrees that tensions between both sides of the debate have now subsided as the music industry has found ways to adapt to the upheaval digital technology brought with it. “We had a small World War III, I call it World War Copyright, where the pro-copyright forces in the creative industries had a significant battle with the anti-copyright forces, including technology companies and consumer groups,” he says. “The music industry were the first industry to feel the importance and impact of the disruptive qualities of digital. I think they were defensive. But I think now theyʼve moved to a much stronger position where they license a large number of organisations to use music in the digital space, and this debate has calmed down considerably. They are generating revenue from the digital space now.”

No musician thinks, 'I must be able to get paid until 2084 or I'm not going to make it'

However, there are some battles that continue to rage. On 1 October, 15 years after the first MP3 players went on sale in the UK, it will finally become legal to copy music youʼve already purchased on CD on to devices like iPhone.

Hargreaves is still critical of this area of the law. “It becomes a laughing stock because everybody knows that copying is going on and there is material from one device to another to take that example, and so long as the law is an ass then some people will behave as if it doesnʼt need to be obeyed,” he says.

Despite this, key players in the music industry lobby, including UK Music and the BPI, have tried to block the legislation until it is clear that rights holders will be financially compensated when consumers make copies of albums and tracks theyʼve purchased, in line with EU law.

The concern, says UK Musicʼs Tom Kiehl, is that if ʻformat shifting’ is made legal as the government is currently proposing, it could allow big companies like Apple to profit from providing and advertising in online Cloud storage lockers (like iCloud and Google Drive), without compensating artists and rights holders for use of their content. “The debate about private copying is not about a battle between us and tech,” he says. “Itʼs more about what the governmentʼs position is… Itʼs not just about ripping CDs and putting them on to your iPod; it would cover all the stuff which would be in the Cloud as well.”

But, for the MMFʼs Jon Webster, lobby groups fighting for compensation over format shifting is a “complete waste of time. If you go out on the street now and say to the people, ʻWhere do you get your music from?ʼ What are they going to say? Amazon, YouTube, Spotify. They are not members of UK Music, they donʼt even sit around the table,” he says.

“The major rights holders will keep all the money [from compensation] and they will not pass it onto artists. They will do everything in their power to keep it all and thatʼs why weʼre so cynical about it. They are lining their pockets. Over the past few years all of the submissions from the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry and BPI they all go, ʻWeʼre doing this for the creatorʼ. Total bullshit. Creators make music because they want to, not first of all because they can see a pay cheque.”

But BPIʼs Chief Executive Geoff Taylor, said firmly in a statement to The Long + Short that this is not the case: “As a trade body, our main role is to represent the recorded music sector, including over 300 independent label members, so itʼs misleading to suggest that we only speak for big rights holders. In fact, rights holders and creators are generally two sides of the same coin, and many of the arguments that we put forward serve the interests of the wider creative community.

“On the more specific point of ‘format shifting’, again Jon Webster is off beam BPI has been clear that it supports consumers being able to make a legal private copy of CDs they have purchased, provided the format shifting exception is consistent with EU law.”

UK Music added in a statement: “UK Music represents the collective interests of the UK’s commercial music industry… We are united in our concern that the Government has ignored important warnings from Parliament and industry about technical flaws in legislation to introduce a much needed exception to copyright for private copying.”

Another problem which will not go away is that of different copyright regulation in different territories. “I think we're still in a state of flux, to be honest,” says Kim Bayley, Director General of the Entertainment Retailers Association. How, she asked in a speech in June, is it right that a digital music story in one country is prevented from selling to consumers in another country? “Once you start that debate with territoriality and copyright, you open the debate about it the copyright law that exists today fit for purpose?”

The future: general election 2015

As Westminster gears up for the 2015 general election, cynics argue that the Governmentʼs softening of its once tough stance on copyright reform is less about a newfound empathy with hardworking songwriters, and more about getting back into the music industryʼs good books. In 1997, the image of Tony Blair sipping champagne with rock star Noel Gallagher became a defining, if short-lived, statement that the new government had captured the cultural zeitgeist. It seemed one that David Cameron was keen to replicate in a reception hosted at the Foreign Office last June for the creative industries, dubbed Cool Britannia II. However, with Tory supporter Gary Barlow in political exile over his tax affairs, the prime minister only managed to pull in a relatively limp selection of musical figures: opera singer Katherine Jenkins; a member of boyband JLS; and pop singer Eliza Doolittle who, when asked if she would vote Conservative at the next election, said simply: “I donʼt think so.”

“All politicians gain benefit from powerful celebrities and that does make them very vulnerable to really quite absurd demands from copyright owners who obviously can persuade and control the artists that they work with ,” says Jon Killock of Open Rights. This view is strongly contested by Scott Walker, director of government relations at PRS for Music, the largest music rights collecting society. “Itʼs a very big accusation to say that the government does things because people lobby them,” he says. “These [artists] are people with lives and livelihoods at stake and they have a genuine interest to protect. A few tickets to events is neither here nor there. Government has continued to do things that we donʼt necessarily agree with.”

For Ian Hargreaves, the lack of uptake of his report’s more radical reforms demonstrates how the music industry fended off another attempt to reform copyright law in a way which would benefit new digital businesses and consumers. “There is a reformed version of copyright that will continue to do a very good job for artists and publishers but it wonʼt do a very good job in the eyes of users.”

For Ian Hargreaves, the lack of uptake of his report’s more radical reforms demonstrates how the music industry fended off another attempt to reform copyright law in a way which would benefit new digital businesses and consumers. “There is a reformed version of copyright that will continue to do a very good job for artists and publishers but it wonʼt do a very good job in the eyes of users.”

Yet as the debate around format shifting continues in the run up to the election, political parties are already making a play for the industry. “Iʼm not going to criticise any part of our creative industries for making sure they protect content and secure royalties going into the future,” says shadow business secretary Chuka Umunna. Speaking at PRS for Musicʼs 100th anniversary gala earlier this year, he set out the partyʼs stall. “I pledge to you this evening, if [Labour] are elected, we will back you.”

And, as Sajid Javid told the BPI in his speech earlier this month: “We [the government] are on your side and we want to help and support you. Because you are the best in the world at what you do. Because you make a huge and vital contribution to British life and British business. And because – to the government, to my department, and to me personally – music really does matter.”