Butterfly effects

During the recording of Thriller, so the story goes, Michael Jackson and his producer got hold of a state-of-the-art drum machine, and eagerly set to work with their new toy. Playing back their first efforts, they were so disturbed by its metronomic perfection that they decided to deliberately programme faults into the drum pattern to simulate human error. As is common to most anecdotes involving Wacko Jacko, the story is almost certainly apocryphal, but true or not, its subtext remains the same: throw your work over to mechanical precision and it risks losing its essence, its humanity. It's a lesson that a lot of currently hot artists would do well to learn.

Over the past few decades, technology has opened up the visual arts to all sorts of possibilities for creating immersive spectacles that go some way to simulating out-of-body experiences. It can be sublime when done well, but lose that crucial human factor – the intangible sense that somehow, flesh and blood and all their myriad failings have had a hand in the process – and you end up with something po-faced and curiously uninvolving. To justify its existence, this latter category is almost always accompanied by reams of impenetrable artspeak.

So I was underwhelmed by the prospect of visiting cutting edge Japanese art collective teamLab's new installation at Mayfair's Pace gallery. According to Pace, teamLab (note the gnomically lower-case initial) is an "interdisciplinary group of ultra-technologists whose collaborative practice seeks to navigate the confluence of art, technology, design and the natural world." Make of that what you will: for my part, I started to feel homicidal urges somewhere around the 'ultra-technologists' mark. And yet, despite everything, I can't stop thinking about this show.

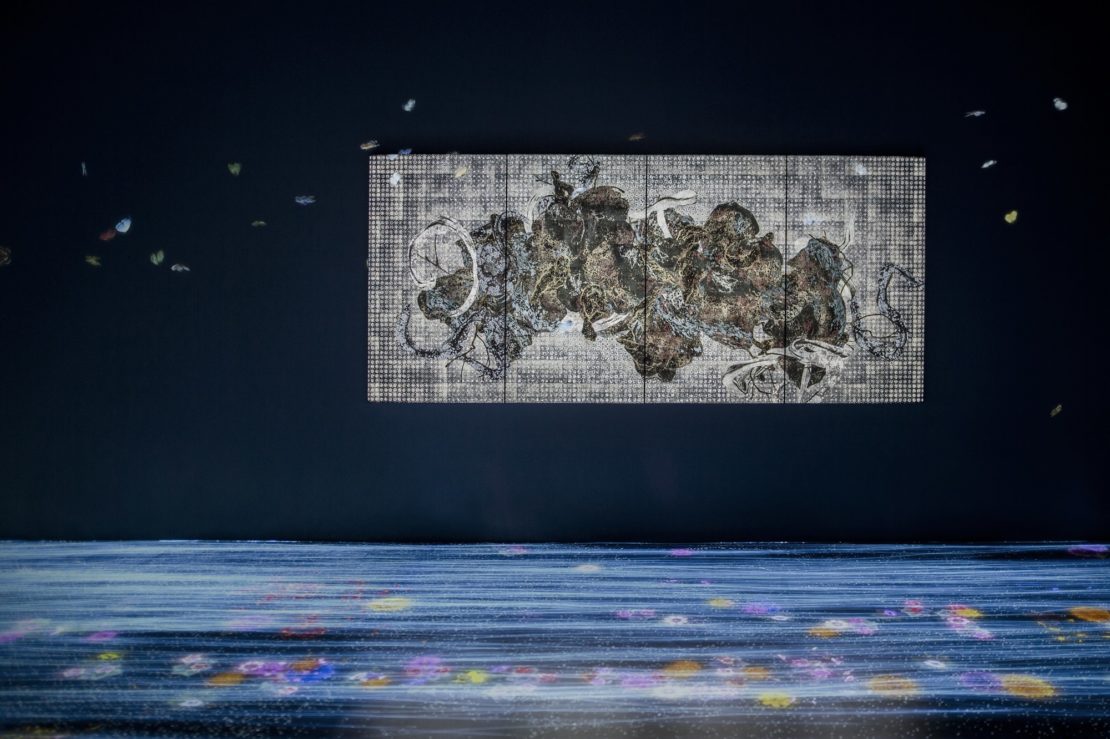

On entering the darkened gallery you are confronted with a blaze of visual simulation, as a one-note ambient soundtrack drones in the background. On the far wall, a digital projection of a waterfall cascades down from the ceiling, sending torrents of water smashing across the gallery floor towards you. Look down and you notice that your feet are disrupting the flow, altering the current ever so slightly the whole way across the room. Meanwhile, pixelated butterflies dance across the walls, swooping down to land on vibrantly coloured patches of vegetation. Two screens on opposite sides of the room show slowly looping calligraphy building up and erasing itself, anchoring the spectacle in a linguistic form that is, unlike the quote above, intended to be impenetrable.

The aesthetic values are unmistakably Japanese, pitched somewhere between a Studio Ghibli film and a mid-1980s Kenzo advert. That is to say, these visuals don't pretend to mimic reality; they offer instead an intentionally stylised approximation of it that seduces the eye into a state of near hypnosis. That waterfall, for example, is composed of hundreds of thousands of lightning-white pixelated strands bunched so tight as to be almost indistinguishable. As they crash down en masse, they give off an eerie blue glow, evoking a strange emotional reaction I have yet to define.

Explore

Review: Installations at FutureFest A new artistic approach to virtual reality Favourited: A two-day event examines the 'The Art of Bots'How this is all done remains a closely guarded secret, though even were it out in the open I suspect few people would be able to get their heads around it. On their own, the graphics would be impressive enough, but what really heightens the achievement is that everything you see will respond to your touch. You can stand in the waterfall, splash about in the virtual torrent as your silhouette distorts the flow of 'water' piledriving its way across the gallery floor. If you stand still against the other walls, exquisite flowers burst into bloom in your stead. You can even splat the digital butterflies fluttering around the room, sending their quivering bodies tumbling to the floor.

This last activity initially entertained me no end, but having zapped several dozen of the creatures, I began to feel remorse for my insecticidal tendencies. Whether or not it's entirely healthy to get worked up over computer-generated lepidoptera is a moot point, but I would hazard that it is part of teamLab's intention. As far as I understand it, the avant-garde technology here is just a vehicle for a sort of 'butterfly effect' environmentally informed message: don't believe that your actions, however small, won't have larger consequences.

This may strike you as so much quasi-Zen claptrap, but I really don't think I've ever seen anything quite like it. Indeed, the only real point of reference I could come up with was with the Zone in Andrei Tarkovsky's Stalker, that most penetrating parable of human weakness. In the film, the Zone is a closed-off, near-mythical area in which the atmosphere itself appears to have attained sentience. If you visit this show, your rationale will tell you that the reams of code that feed into the display have no such capacity – and yet, as it lulls you into an ever more meditative state, you may well find yourself suspending disbelief.