Canned designs: Rip it up and start again in Paris

If, as some contend, architecture is really just a priapic parlour game, then Le Corbusier's plan Voisin is the equivalent of short-man-in-a-sports-car syndrome.

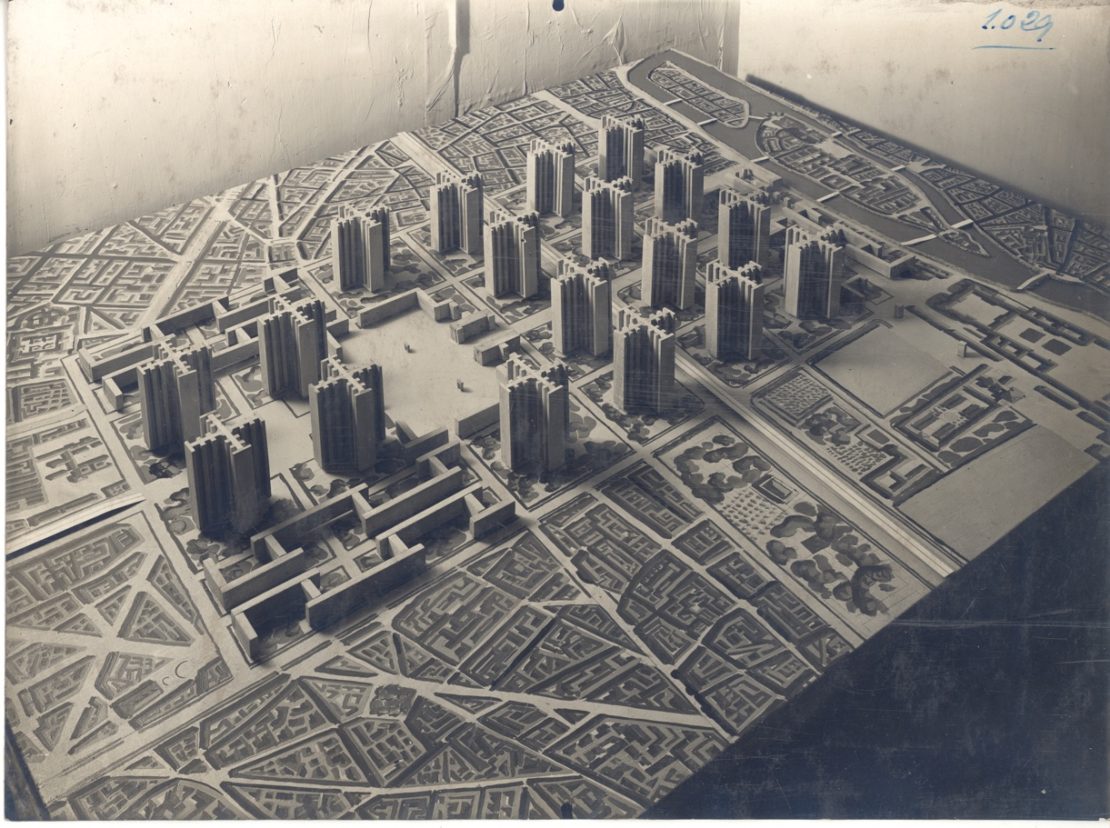

Le Corbusier was a grouchy Swiss polymath who went on to dominate the design world in the 50s and 60s. But back in 1925 his plan to replace the buildings of central Paris with 18 identical skyscrapers was met with so much hostility that French commentators of the time had to put their cigarettes down to get their invective out. Le Corbusier's idea was to create a new future without resorting to the past. Yet Parisian grands projets have been with us since Haussmann straightened the city's crooked streets into grands boulevards in the 1800s; and the big ideas didn't stop with Le Corbusier either.

While the Plan Voisin's drama and violence – knock down central Paris, remember – was immediately chucked into the bin with yesterday's tattered Le Figaro, Le Corbusier's vision did actually inspire later projects. La Defense, Paris's proto-Canary Wharf business district on the west of the city is a forest of skyscrapers that Le Corbusier would surely have smiled about.

Developed from 1958 and still not really finished, this is the part of Paris that introduced a city previously unaccustomed to tall steel and glass buildings to the world of thrusting towers. They're not the same height or the same shape as the ones in the Plan Voisin, but the sentiment is the same. From above, La Defense's shape looks exactly like some planner has done nothing less than flop out his tackle onto the map and draw round it.

Today, though? Look at the new tall buildings going up in Manhattan, London or Shanghai. Maybe we’re closer to Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin than we – or he – could have ever imagined

In the 1960s, Paris's planners tinkered once more, and the results also recall the Plan Voisin. The sprawling outer city housing estates that went up in banlieues such as Clichy-sous-Bois consisted of clusters of tower blocks that didn't look so different from Le Corbusier's ideas 40 years prior.

While La Defense has prospered, these estates have fomented extremism and dislocation – not so much because of the architecture per se but the lack of public transport, jobs, social services and cultural amenities out in the 'burbs.

Paris likes to keep its problems at arm's length. When Robert Hughes stopped by at a banlieue in 1979 when filming his moany, bravura art history epic for the BBC, The Shock of the New, his verdict on the – to him – terrible tower blocks he saw was damning: "Gimmicky, condescending, Alphaville modernism. After this, who believes in the idea of progress and perfectibility any more?" Alphaville – Jean Luc Godard's rich 1965 noir film – predicted a Paris of some time over the horizon taken over by towers which demeaned the citizen. It made Parisians freak out about the future. Yet Le Corbusier's original Plan Voisin didn't contain any of this muck and grit.

Was he optimistic or stupid? His original drawings depict swathes of green space between buildings, aeroplanes gliding around, people taking tea on terraces. He didn't want to unleash a demon, but he ended up doing just that.

Today, though? Look at New York – a rash of new tall buildings going up all over Manhattan. The same in London, Shanghai, Melbourne. Maybe we're closer to Le Corbusier's Plan Voisin than we – or he – could have ever imagined.

More in this series

Canned designs: Berlin's paths not taken

Canned designs: Cars on roofs in Staines

Canned designs: Manhattan's doomed domed city

Canned designs: Two sides of Glasgow

Canned designs: Tokyo's floating city