Mining for Argentina's financial future

In the village of El Chaltén in Argentine Patagonia, a small absurdist ritual takes place each day. Every morning, at the deli counter of the general store, its owner Felipe cuts two or three large salamis into dozens of smaller sections. He wraps each one in clingfilm, carefully weighs it, and attaches a printed-out price sticker accordingly. Each new section of salami has a different price, correct to two decimal places.

In El Chaltén, fresh food arrives once a month. In between times, it lies in boxes on the shelves of the two small grocery stores and slowly rots. Felipe's salamis are popular with the backpackers who flock here between September and April to trek in the shadows of Cerro Torre and the Fitz Roy massif. But there is a problem. Each time they go to pay, the price is rounded up to the nearest whole figure – sometimes more. Felipe's painstaking cutting and weighing and pricing is ultimately overruled by the cashier. All along, it was an exercise in futility. Why?

In Argentina, there is no loose change. This is not a new problem. Back in 2008, Time ran an article under the headline, 'Spare Change? There's none in Buenos Aires'. The article pinpointed a black market involving bus companies and money transporters who hoard coins in order to resell them. At the time, buses in Buenos Aires did not accept paper currency, so their intake of coinage each day was massive. "In a raid on the Maco transport company in Buenos Aires," the article reported, "police seized 13m coins. The central bank promptly returned the money to Maco – in bills." In 2009, the SUBE smartcard was introduced on public transport in the city, but many have expressed concerns over the amount of personal data the cards collect. The lack of coinage remains an issue. That is why you don't get change from stores in Buenos Aires or El Chaltén: the shops simply don't have any – or, if they did, they certainly wouldn't just be giving them away.

It's hard not to observe the sad historical irony of Argentina's money troubles – especially the ongoing scarcity of hard currency. Argentina, after all, means Land of Silver

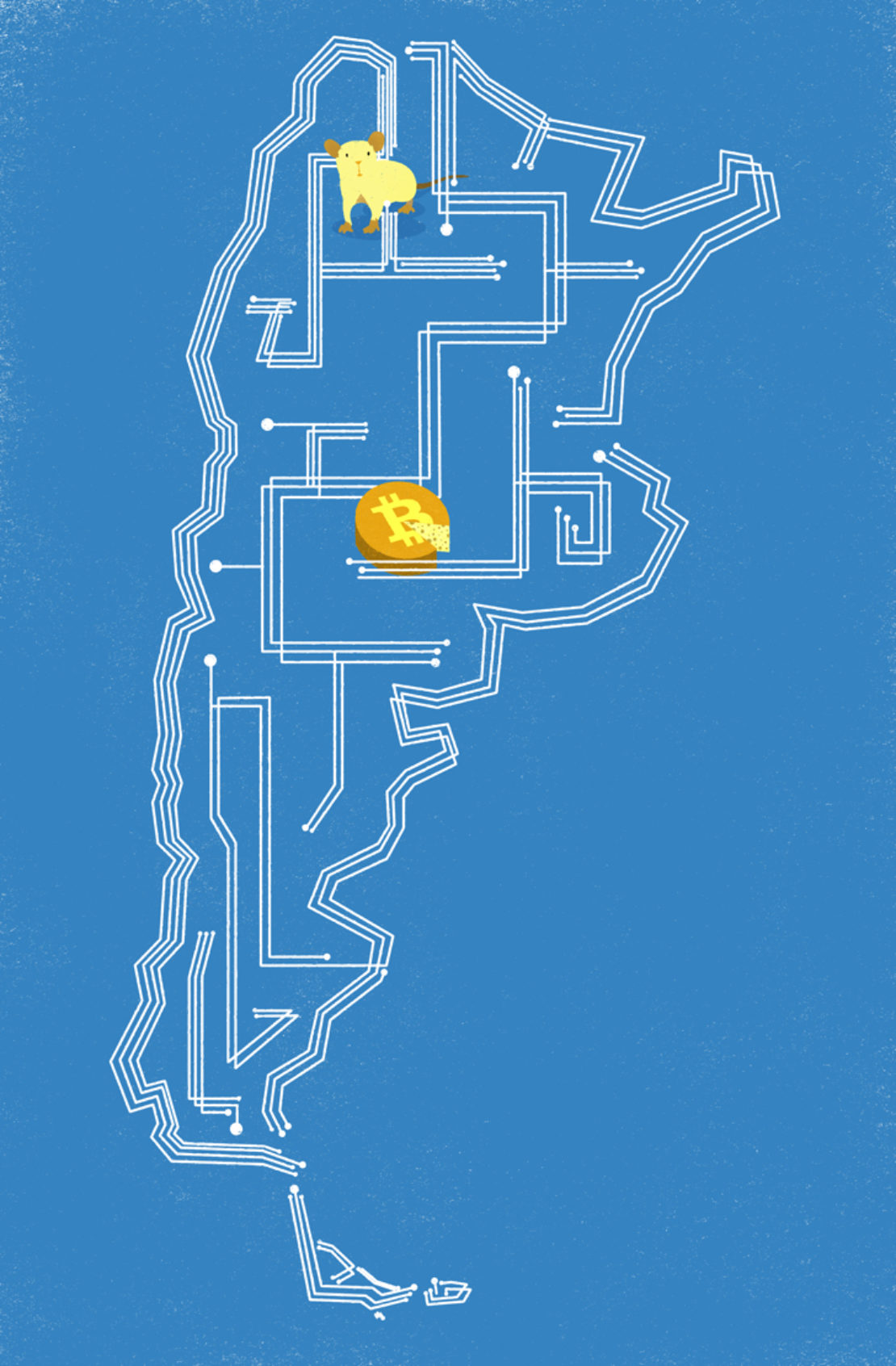

The lack of coin currency is just one symptom of the chaotic nature of Argentina's economy. It hasn't always been like this: from the mid-19th century to the early 1930s, the fertile lands of the Pampas fuelled rapid economic growth. But thereafter, decades of political instability have wreaked havoc upon the economy. Today, the mining industry promises new investment in Argentina. It is not lack of natural resources or industry holding the country back, but politics and economic mismanagement. And then there's bitcoin: heralded by some as the solution to all Argentina's economic woes, but for others merely another flash in the pan.

In recent years Argentina has been hit by crisis after crisis: hyperinflation, unemployment, recession, sovereign debt defaults, political scandals and cronyism.

At the same time, 2014's 'selective default' resulted from a US court order that granted a so-called 'vulture' investment fund called NML Capital the right to obtain 100 per cent of its claims against the Argentine government, after bondholders demanded to be paid back in full the debt which the country defaulted on in 2001. The decision by president Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner to go ahead and make payments on the country's restructured debt, without also paying NML, may have drawn praise from international commentators, but it has hardly helped the economic situation at home. Stringent limits on the flow of currency out of the country have been introduced to combat inflation. But these have caused the country's reserves to decline to what the Financial Times has termed "dangerously low levels". Due to the default, Argentina can no longer borrow from abroad. The fiscal deficit is now around 7 per cent of national output and the government is printing money. Inflation has been rampant.

Explore

In search of the renewable city Canned designs: Rip it up and start again in Paris Good ideas that didn't pan out, part 1: free moneyFor ordinary Argentinians and visitors alike, the most noticeable effect has been the booming black market. Until recently, tourists have been advised to take advantage of the 'blue dollar' rather than the official exchange rate at the banks. The dual rate emerged after the government put into place a number of restrictions on currency exchange in an attempt to prop up the peso, attempts that have only very recently been abandoned, crashing the currency. Along Calle Florida in Buenos Aires, the black market traders are known as arbolitos (little trees) as, I'm told by one local: "They stand rooted to the spot, dispensing 'the greens'." A few months ago, the official exchange rate was around 9.5 Argentine pesos to the US dollar. The blue dollar offered over 16 pesos. Following the major currency devaluation in December, the official rate has jumped to around 13 pesos, while the blue dollar has fallen to near parity.

The everyday uses of bitcoin in a country like Argentina are the early lab tests of radical financial overhaul

It's hard not to observe the sad historical irony of Argentina's current money troubles – and especially the ongoing scarcity of hard currency. Argentina, after all, means 'Land of Silver'. You'd think the place would be piled high with the stuff – the early Spanish and Portuguese colonialists certainly did. The origins of the name can be traced right back to the very first voyages in the 16th century to the Río de la Plata, the estuary formed by the confluence of the Uruguay the Paraná rivers. Today, the estuary forms part of the border between Argentina and Uruguay. Buenos Aires lies on its western shore, Montevideo to the north. Río de la Plata means River of Silver.

The river was supposedly fed by the Sierra de la Plata (Silver Mountains). In the early years of the 16th century, repeated attempts to locate this source of unimaginable wealth all ended in failure. Nonetheless, before long, the rumours of silver had been solidified in the form of a map: Portuguese cartographer Lopo Homem labelled the region as Terra Argentea (ultimately derived from the Latin for silver, argentum) in his elegant (if vague) map of 1554. Then in 1602, Spanish priest and explorer Martín del Barco Centenera published a poem of some 10,000 verses. Its name? La Argentina. Whatever the accuracy of Homem's map or Centenera's poetry (which, incidentally, contains tales of human-shaped fish), what is clear is that a legend was born. Argentina was now officially the land of silver.

The causes of Argentina's present-day difficulties are complex and deep-rooted. Colin Lewis, professor at the Institute of the Americas at University College London, blames the country's ongoing economic volatility on profound disagreement over economic strategy among political groups and interests. Argentina's boom years came between 1880 and 1905, thanks to the export of livestock and grain commodities. Though the first world war and the Great Depression hit Argentina hard, it was not until after the second world war that the country's difficulties really began. The 40s and 50s were the era of Juan Perón, Argentina's charismatic and populist president. Under his government, the central bank, railways and other key services and industries were all nationalised. But Perón, becoming increasingly authoritarian, lost the support of the Catholic church and was overthrown by a military coup in 1955. Under military rule, Argentina's economic policies moved rapidly right, before lurching left again with the return of Perón in 1973.

These decades of instability made meaningful long-term investment all but impossible. In many countries, economic crises lead to revolution, but in Argentina it may be that the inverse is true: that political upheaval is not the symptom but the cause. Lewis agrees. "Conventionally," he says, "it was argued that most crises experienced by the country used to be economically determined – collapse in commodity prices, global financial collapse, and so forth; now that volatility is largely domestically driven – namely, policy-determined."

Donna Guy, emeritus professor at the Ohio State University and author of Creating Rights in Argentina, 1880-1955, agrees that Argentina's unique political history has been a significant problem. "The emergence since the 1980s of the Peronist Party as the only successful national party has… complicated [a situation] that often veers between redistribution politics and economic retrenchment. But the key issue for Guy is: "Argentina has very modern infrastructures that rest on shaky foundations." Without stable infrastructures and traditional industry, modern developments can exacerbate underlying problems. In agriculture, she says, tractors arrived before petroleum self-sufficiency; industry relied on imported coal; then free university education created doctors and lawyers, not engineers. These issues are deep-rooted, and there is no quick fix. "You can blame Peronism," says Guy, "but no political party could solve these issues."

A year ago, the thing to do was to bring currency into the country using Azimo, one of a number of money transfer startups looking to capitalise on the growing desire to move money around the world. Azimo's brand identity is bright and fun. But the location of the actual exchange (a small, dingy room tucked away in a busy train station) is a far cry from the cutesy website graphics that feature a paper aeroplane and a letter delivered by hot air balloon.

It's easy to see why companies like Azimo are targeting Argentina. Money transfer is a fact of life here. For years, locals have resorted to bizarre ways to bring foreign currency into the country. A designer who lived and worked in Buenos Aires for nine months tells me: "In order to get dollars, we would take a regular trip to Colonia in Uruguay and get to the banks early in the morning before the other Argentinians drained them of their reserves. It's a very common trip for porteños." And where there's money being transferred there's money being made: following the announcement of $20m worth of investment last summer, TechCrunch recently estimated Azimo, a British company, to have a total valuation at just under $100m.

It is into this currency cauldron that bitcoin, the much-hyped digital currency and payment system based on an open source computer algorithm, has arrived, amid much debate. Bitcoin has no central administrator and a fixed supply, which models scarce resources such as gold. Because, unlike banks, it does not require intermediaries, transfer fees are much lower than those for normal credit cards. This has been one of the main reasons the currency has gained in popularity. According to Coinmap, a database of bitcoin-using businesses, nearly 7,500 bricks-and-mortar businesses currently accept the currency.

The currency has also been prone to extreme fluctuations in value. In 2011, for example, the value of one bitcoin rose from about $0.30 to $32 before returning to $2. At the time of writing, one Bitcoin is equal to $430 – well up on its early years but under half of its 2013 peak, when it traded at more than $1,000 apiece. Such volatility has seen many advise caution towards bitcoin. Most consider it more as a useful as a tool for transaction, rather than a reliable place for serious investment, although its underlying blockchain technology has been garnering a lot of attention in finance circles recently.

In many countries, economic crises lead to revolution, but in Argentina it may be that the inverse is true: that political upheaval is not the symptom but the cause

Whatever bitcoin's global future, what is clear is that it thrives in Argentina because of the country's recalcitrant economy. Argentina is the country with the single greatest potential for digital currency, according to Bitcoin Market Potential Index, which ranks the potential utility of the currency across 177 countries. Use of bitcoin doubled between mid-2014 and mid-2015, primarily among small businesses. Tech entrepreneur Joan Cwaik estimates that Argentina's bitcoin users are trading approximately $70,000-$80,000 over the counter per day. Coinmap currently lists 145 venues that accept bitcoin in Buenos Aires alone. London, by comparison, boasts 90, New York 87. In the centre of Buenos Aires, just a short walk from the arbolitos of Calle Florida, is the "Bitcoin Embassy", a four-storey building home to a number of startup bitcoin businesses. Companies based behind its drab, grey front door include digital currency e-commerce platforms such as Bitpay and BitPagos, an exchange site called CoinMelon, and several other software startups. Last year, Argentina's largest social network Taringa! started using bitcoin to share revenue with users.

In March, the New York Times ran a story headlined "How Bitcoin is disrupting Argentina's economy". Journalist Nathaniel Popper introduced his readers to opportunist money trader Dante Castiglione. "His occupation," notes Popper, "is one of the world's oldest." But there is a difference: Castiglione buys and sells not pieces of silver but bitcoins. His clients include freelance musicians working for international clients as well as companies that deal in bitcoins on a larger scale. The service he offers individuals and businesses is the ability to circumnavigate the country's stringent currency regulations.

For many, the practical everyday uses of bitcoin in a country like Argentina are the early lab tests of radical financial overhaul that could have wider implications for the global economy.

Of most interest to many investors lately has not been the bitcoins themselves but the technology that powers them. All bitcoin transactions are recorded in a public ledger called a blockchain, which operates with no central authority. The blockchain is maintained by a network of different users ('miners'), all running the bitcoin software. New bitcoins are created as a reward for these miners allowing their computers to be used to verify and record transactions. Almost every major bank, including JP Morgan, Barclays and UBS, is investigating how to put together their own blockchains. Many startups are working on it too.

Explore

Is Paris a city stuck in the past? How Japan, the supposed 'sick man of Asia', might be a model for us all Good ideas that didn't pan out, part 5: alternative bankingAlthough digital currency innovations may be of long-term interest to the world's banks and entrepreneurs, for the Argentine economy in the medium term it is the more traditional forms of mining that promise employment and investment. The Sierra de la Plata may have proved illusory: despite the best efforts of the colonising Spanish in Argentina, at least, the silver failed to materialise. However, according to a news agency report: "One of the main demands from the companies in mining is allowing the transfer of profits overseas, which at the moment has been suspended (given the shortage of hard currency that Argentina is suffering) and has drastically limited access to US dollars.". Likewise, Bloomberg has reported that the world's largest mining companies are looking to invest up to $5bn in Argentina, but only if there is an easing of capital restrictions following November's election.

All eyes are now on new president Mauricio Macri, who campaigned on a platform of economic change. For Macri, the big challenge is to get the economy back on track in a way that addresses the infrastructure voids that Donna Guy has identified. In a sign that volatility may finally be at an end, politicians on all sides seem to be in broad agreement as to the cause of Argentina's problems. As the country headed to the polls for a runoff election in the autumn, both Macri and his opponent Daniel Scioli, of the incumbent Front for Victory party, shared the view that Argentina must reach an agreement with foreign creditors, bring down inflation and attract foreign investment. The main difference between the two is in terms of timescale: Scioli favoured gradual reform; Macri an immediate removal of capital controls and the free flotation of the peso. He's been true to his promise. Since taking office, Macri has already devalued the peso by nearly 30 per cent by floating it, slashed export taxes in favour of influential farmers, and scrapped many of the currency controls put in place by his predecessors. The pace of change has surprised some and angered others.

Donna Guy offers some hope: "Don't underestimate Argentina," she says. "If it could solve problems of cronyism and corruption, that would help a lot." Colin Lewis also pinpoints the election as a key moment, but he is less optimistic. "The immediate future will see a dramatic 'correction', as economists would have it, after the election," he told me, prior to Macri's inauguration. "This means that the exchange rate will be 'corrected' and that effort will be made towards narrowing the fiscal deficit and reducing the trade imbalance." But there is a price: "This," warns Lewis, "will be extremely painful."