Living fossils: the slow and steady approach to life

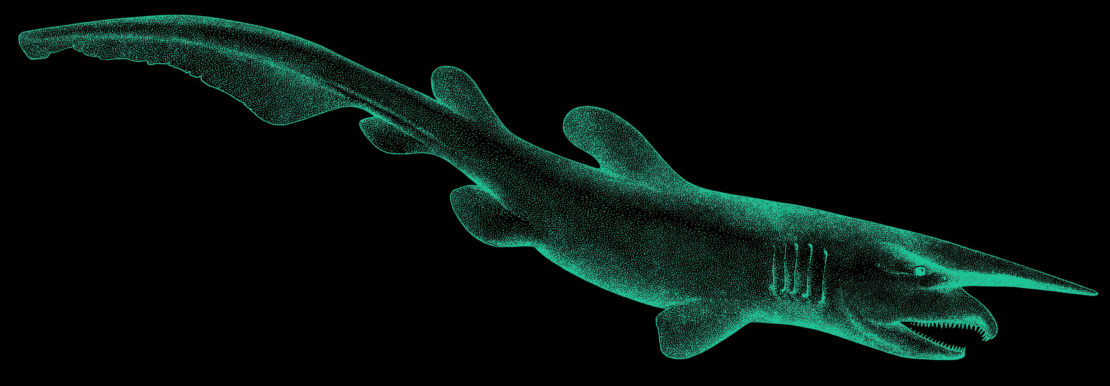

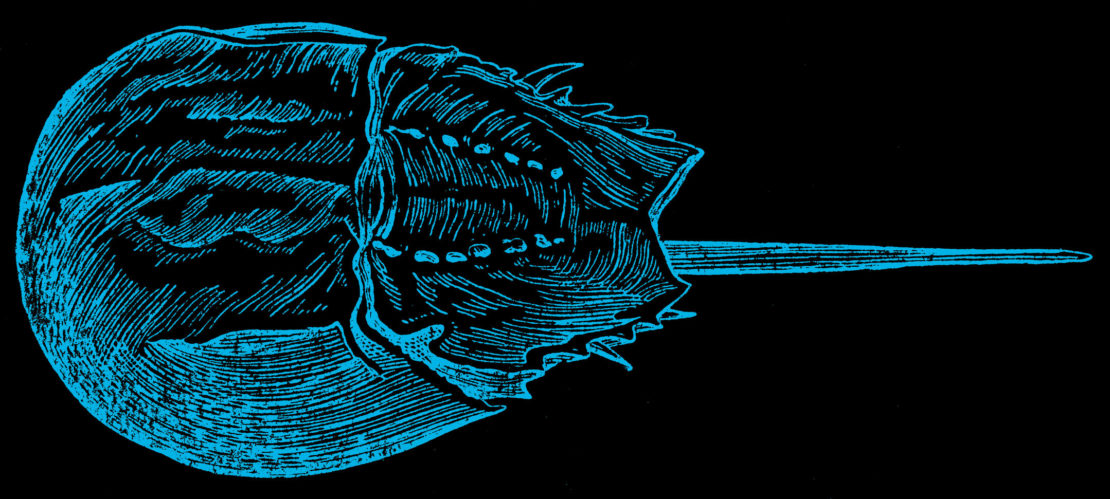

Even the names of species referred to as 'living fossils' sound extra-terrestrial: goblin shark; horseshoe crab; comb jelly; crinoid. When a new piece of research or finding about one is reported in the news, the words 'alien' or 'freaky' are often attached. They come in all kinds of peculiar shapes and sizes. The primordial frill shark, for example, is horrifyingly ugly. Though more attractive, the comb jelly, pulsing with neon disco lights, seems utterly otherworldly. The sea lily looks like a witches broom crawling across the ocean floor.

'Living fossils' is an informal, non-scientific term coined by Charles Darwin, and refers to species that look as they did hundreds of millions of years ago. Relics of a bygone age, they are examples of an otherwise extinct group with no close living relatives. While still evolving, as everything is, their physical appearance has remained comparatively stagnant. For these creatures, if it's not broke, why fix it?

Explore

Practical science: life in a labThe label is used far and wide but it can be over-simplistic for such a varied and complex collection of organisms. "It's a hook on which we can hang concepts," says Professor Charles Messing at the Nova Southeastern University Oceanographic Center. "But there's no one-size-fits-all."

The Tuatara lizard, for example, might look the same as it did 220m years ago but it's evolving at a DNA level faster than any other animal on earth. The coelacanth, Messing points out, evolved to live in the sea today, whereas its ancestors lived in freshwater. For creationists who use living fossils as evidence to deny evolution, these facts aren't helpful.

Why are we so drawn to these mysterious survivors? "They're evocative, and harbingers, of another time," explains Messing, who specifically studies sea lilies and feather stars. In nature, some semblance of stagnation can make sense.