New York City Flops

New York, a city which seems to reinvent its own urban landscape every week, can be ruthlessly unsentimental when it comes to its heritage. Consider the 1910 Beaux-Arts masterpiece Penn Station, inspired by the Gare d’Orsay in Paris. It was demolished in 1963 when, under financial pressure, the Pennsylvania Railroad sold the air rights to the property. A sports and office complex was built in its stead and the station moved below ground. Then there’s the case of the Domino Sugar Factory: an enormous, landmark building on the Brooklyn waterfront dating from 1882. It’s been in the headlines recently as it hosted the artist Kara Walker’s huge sugar sphinx sculpture; but in March this year the City Planning Commission signed off on plans for a $1.5bn redevelopment of the property, including a high-rise apartment building.

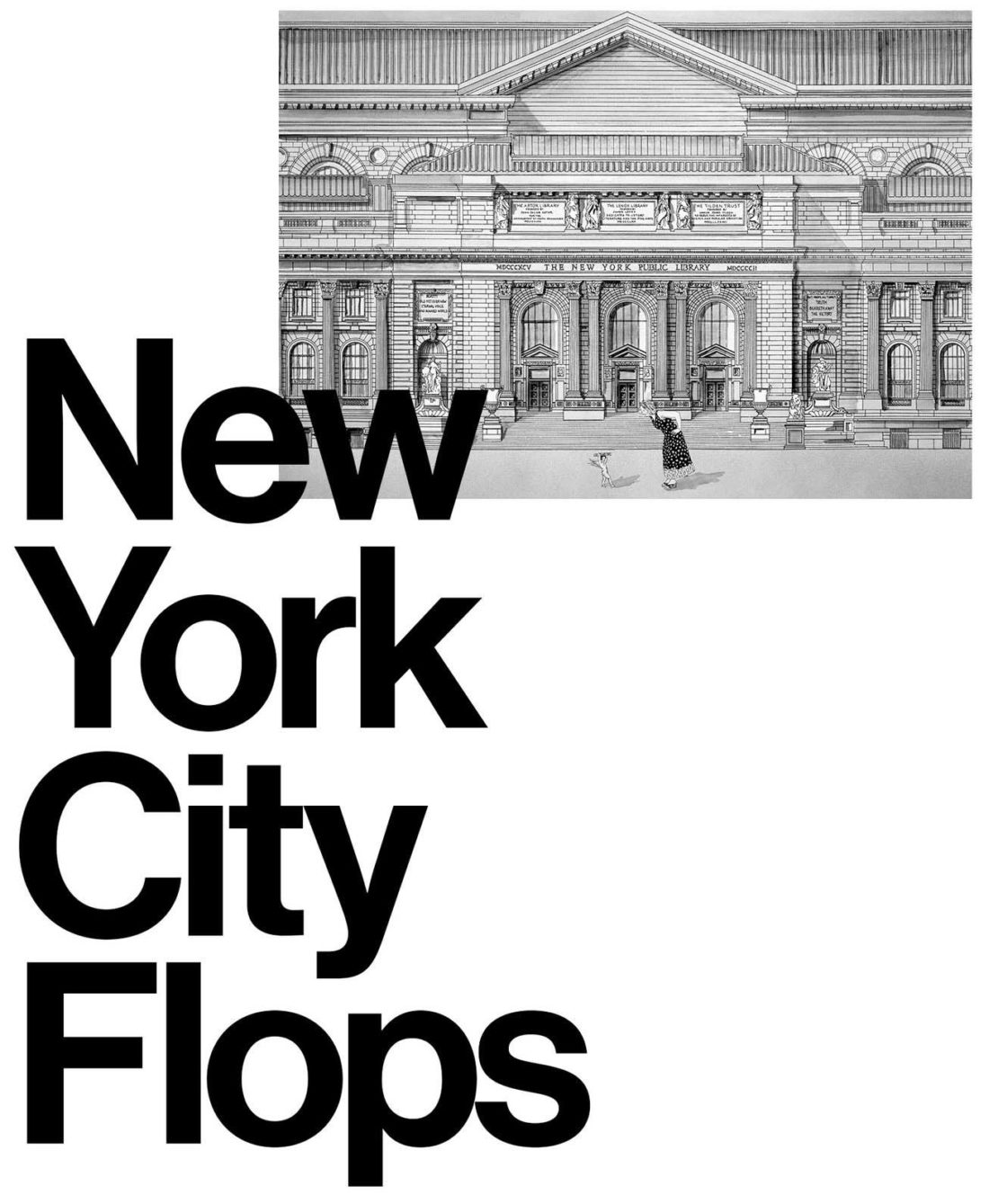

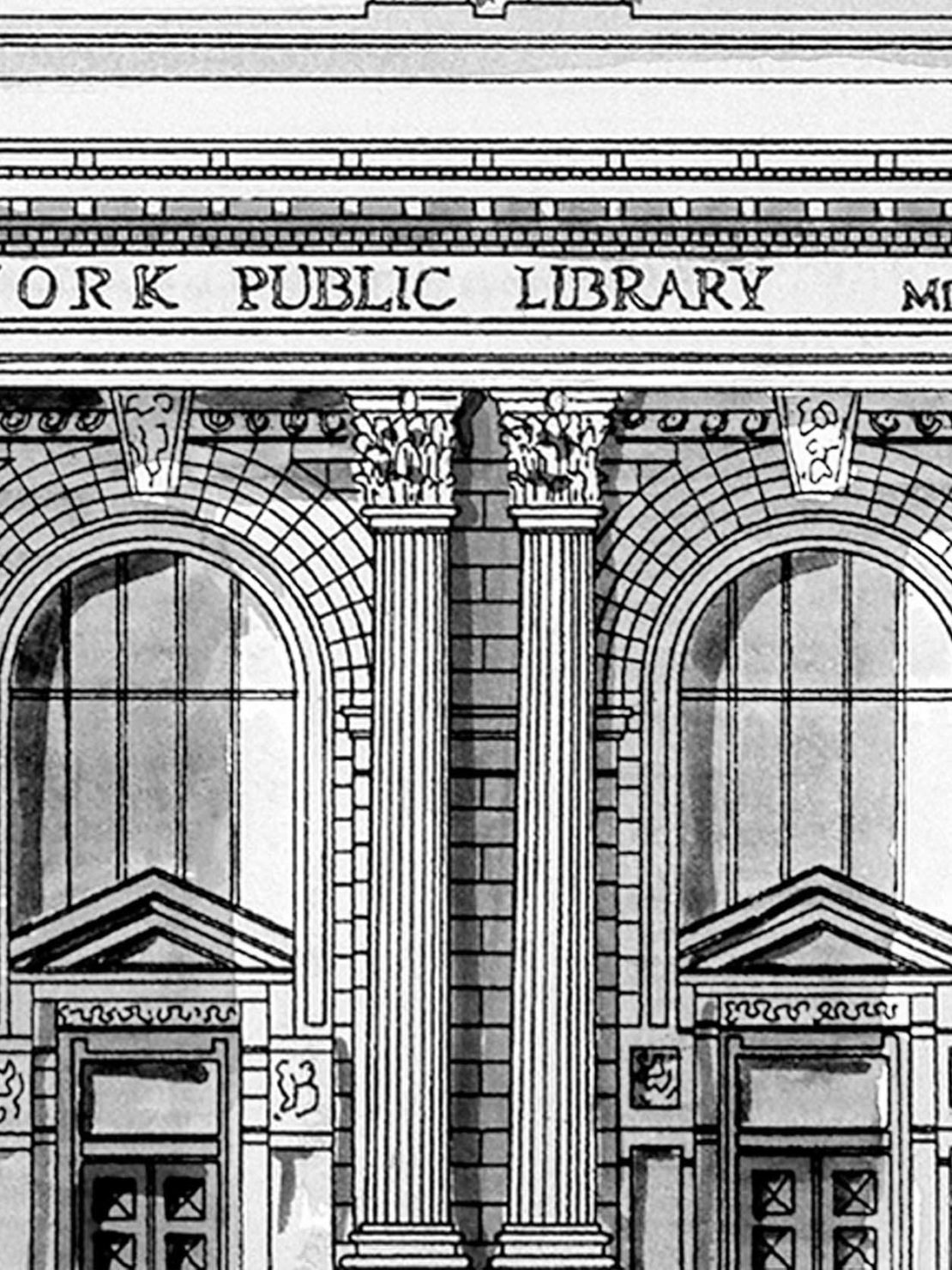

And then there’s the New York Public Library's main building in Bryant Park (often referred to as the NYPL): all 20,000 white marble blocks of it a National Historic Landmark since 1965. On a hot Monday afternoon in early June, those thronging its steps fall into two groups: tourists, who take artful selfies of themselves in front of the building’s columns or beside its famous stone lions; and scholars, biographers, students, academics, writers, amateur researchers and the longstanding resident oddballs that venerable institutions like this invariably attract. As these two camps attest, it is both a monument and a resource: a tourist attraction, but also one of the world’s finest research libraries. Its collection of 8.2m books makes it second in size only to the Library of Congress in Washington, DC. But unlike the Library of Congress, the NYPL is open to everyone for free.

The library always seemed like an institution impervious to change. Now, though, an ongoing and controversial set of plans for its drastic renovation have demonstrated that even this most sacrosanct and seemingly inviolable of cultural institutions is vulnerable. When the ongoing saga of what the NYPL calls its renovation and what others call its desecration reached a crisis point earlier this year, it became clear that the case of the NYPL isn’t just a New York story, but an internationally high-profile set of questions about our cultural institutions and their futures. What should a library be in our digital age and, more pragmatically, what can it be? Who decides what ‘relevance’ means and by what metrics? How can organisations create an alliance for change and persuade a sometimes sceptical public that reinvention is actually required? In short, how can a venerable, privately funded public institution renew and sustain itself, remaining financially viable without compromising its integrity?

These are fraught questions and cultural institutions around the globe are looking to the unfolding story of the NYPL for answers. That story begins in 2008, when Stephen Schwarzman, the billionaire CEO of the global investment firm Blackstone, gave the library $100m. Soon after, the library’s main building was officially renamed the Stephen A Schwarzman Building, a fact that its visitors and readers continue to cheerfully ignore. (Few cab drivers would know where to go if their passenger asked to be dropped at the Schwarzman Building.)

Less ignorable, however, was Schwarzman’s name carved onto the front of the building in enormous letters, a horrifying ‘disfigurement’, many thought, on the hitherto unblemished face of its 1911 Carrère and Hastings facade. The local community board had opposed them on the grounds that they were, “excessive and unnecessarily intrusive to this iconic facade.”

At the time, the New York Times reported that Schwarzman’s enormously generous gift was, ‘given without any conditions’. But in 2013, during a TV interview with public broadcasting chatshow host Charlie Rose, it emerged that this may not have been the case. Discussing accountability around the gift, Schwarzmann said “the advantage here is that I knew how they were going to spend it.” He added: “This is because I was on the board of the library and they hired one of the major consulting firms to figure out how to reconfigure the library system, create a modern lending library in the main branch and be able to deliver better financial services and put themselves in better shape. So what happened is the head of the library came over to visit me, as these things tend to work and suggested I give them a hundred million dollars, they could then get a lead gift to implement their plan.”

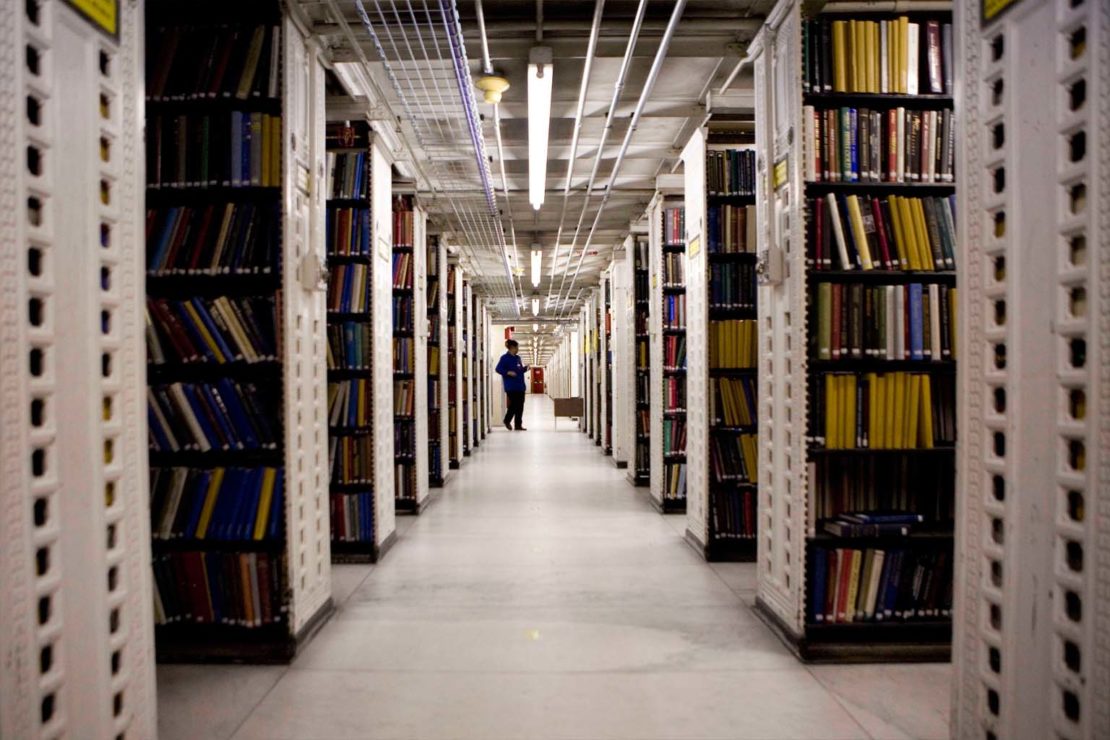

It seems it was agreed, albeit verbally, that Schwarzman’s gift was to go towards the Central Library Plan, or CLP. All this was decided in secret and the news only broke publicly in 2011, when Scott Sherman, who is now writing a book about the NYPL, wrote a lengthy cover story for The Nation. In it, he revealed plans to remove 3m of the books in the stacks below the famous Rose Main Reading Room and ship them to a storage facility in New Jersey. Meanwhile the stacks themselves, all seven storeys of them (the centrepiece of the building both structurally and aesthetically) would be gutted on the grounds that retrofitting them to be humidity controlled was too expensive. In their place, a Norman Foster-designed structure would be built containing fewer books and more space for computer users. This was all expected to cost around $300m: money which, it was pointed out, would surely be better spent on New York’s 87 branch libraries, many of which remain desperately in need of things as basic as chairs.

These are bad times for library budgets. The Seattle Public Library, for example, has suffered such extreme funding cuts that it was forced to implement salary reductions for staff and close branches for a week in August 2012. This followed an expensive revamp of their central branch. An example, it seemed, of the dangers of pouring money into one flagship building and neglecting its smaller branch libraries.

The question that Sherman’s piece posed – “Will the new president’s mega-million-dollar makeover of the main library scare off scholars and leave the branches begging?” – seemed to be answered in the affirmative.

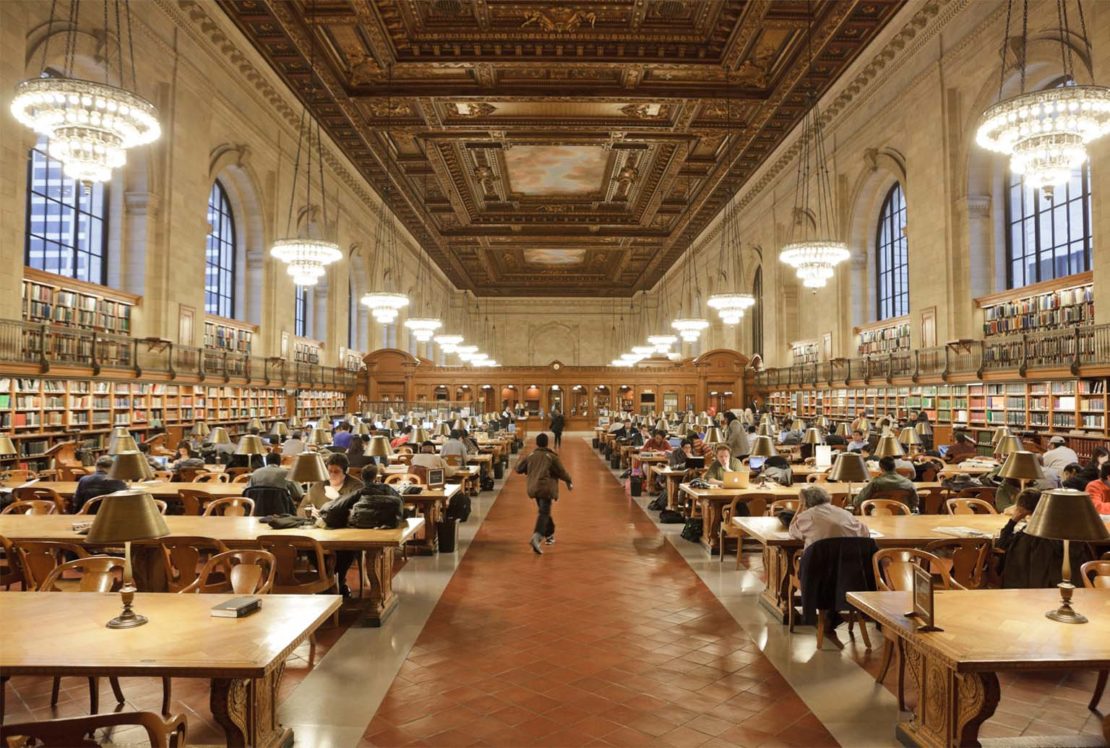

Charles Warren, an architect who has written about the NYPL’s famous architects Carrère and Hastings, was unequivocal about what a terrible idea it was to remove the stacks. He told Sherman: “The building is a machine for reading books in. The stacks are part of what the building is. There’s an idea there: that the books are in the centre and they rise up out of that machine into the reading room to serve the people. It’s a whole conception that will be turned on its head by ripping out the stacks. It’s a terrible thing to do.”

The building is a machine for reading books in. The books are in the centre and they rise up out of that machine into the reading room to serve the people

It included this statement: “One of the claims made about the CLP is that it will ‘democratise’ the NYPL, but that seems to be a misunderstanding of what that word means. The NYPL is already among the most democratic institutions of its kind. Anyone can use it; no credentials are needed to gain entry. More space, more computers, a cafe, and a lending library will not improve an already democratic institution.”

If there were any non-library affiliated voices supporting Marx and the plans, it was hard to hear them over the din of opposition. One of the most circulated mainstream media pieces opposing the plans was by biographer Edmund Morris, a longstanding user of the institution who, under the headline Sacking A Palace of Culture, wrote in the New York Times maligning what he saw as the corruption of a library “long devoted to reference, into what sounds like a palace of presentism.”

Morris’s florid piece had a whiff of snobbery about it (“the marble floor nowadays is loud with the squeak of Reeboks”); but many of those mobilising against the plans are in fact deeply sympathetic to NYPL president and CEO Tony Marx’s agenda of democratisation and his emphasis on education. Before coming to the NYPL, 55-year-old Marx was president of Amherst College, where making the college more accessible to students from lower income families became one of his priorities, enhancing scholarship aid. Many subscribe to those ideals; it’s their misguided, even self-destructive implementation they object to, as well as what seems to be financial mismanagement on a huge scale.

Those involved in the Save the NYPL campaign include Susan Bernofsky, an award-winning translator of German literature, a Guggenheim fellow and a professor at Columbia University. “The crazy thing about this dispute is that it’s somehow pitted the library advocates as if we’re against progress,” she told me, “which we’re not.”

Like many of her peers, she agrees with the library that “they should be doing more educational and general interest programming”, but is adamant that getting rid of books is not the right way to go about that.

“The idea now seems to be that basic level education is good enough for the masses,” she explains. “There’s this feeling that high-level information and the desire to have immediate access for that is this very elitist idea, whereas no, actually, that’s a democratising idea, that high-level information is available for free, quickly, for everybody. It’s the only research library in all of New York State that’s open to the public. It’s the only library you can go to if you don’t have money. High school students who want to get serious about school papers – it’s their library, it’s their resource. And then people who aren’t students, just people from the general population who want to research some topic. This is the place.”

She also detects a self-fulfilling defeatism in the library’s strategy. “When the library moved 3m books out of the library a year and a half ago under the cover of darkness, nobody knew about it. No discussing, no announcements, suddenly just all the books were out of the building.”

As she sees it, they’ve effected a specious strategy. She explains: “They created a fact on the ground that is going to be almost impossible to undo. By keeping the books off-site and making the library more difficult to use, the library will in fact succeed in decreasing the number of users, thereby proving that they were right to remove the books, since the books are not being used. They’re making the library harder to use so people won’t use it. It becomes already much less of a public resource. To make it valuable again you would have to put back the clock a year and a half before the books were removed, fix up the stacks, retrofit them, bring the books back.”

Or, as Zadie Smith put it, “Neglected libraries get neglected, and this cycle, in time, provides the excuse to close them."

Some advocates worry that the example of the Corcoran Gallery of Arts, Washington’s oldest art museum, is a harbinger of the doom that might befall the NYPL. The Corcoran, under the stewardship of a board whose members, for the first time in the institution’s history, had no professional background in museums or the arts has, as one Wall Street Journal article put it, “consciously willed itself into oblivion,” culminating in the sale of its own building. The article concluded: “The untold story of our time is the emerging crisis in nonprofit governance, where boards embark on policies that go against – and even imperil – the mission of the institution they are charged to oversee and protect… It›s impossible to ignore the shift away from boards populated by individuals who understand the values of the institution and the discipline.”

When Marx became president and CEO of the library in 2011, he inherited the Central Library Plan from his successor Paul LeClerc; but from the start he seemed to apply himself enthusiastically to its execution on the grounds of both democratisation and financial sense. As he said in a statement, “By combining three facilities into one, we expect to have up to $15m more to spend annually.”

Until, that is, last February, when the Save the NYPL campaign received a boost in an unlikely form: a photo of a man eating chicken. New Yorker Matthew Zadrozny has been going to the library for 20 years, ever since he was a kid. He was eating his lunch of fried chicken out of a camping pot when Brandon Stanton, who runs the award-winning photoblog Humans of New York, spotted him and asked for a picture. Zadrozny, who days before had been handing out fliers on behalf of the Committee to Save the New York Public library, seized his chance to deliver a message to accompany his photograph: “When everything is finished, one of the greatest research libraries in the world will become a glorified internet cafe.” The words swiftly became a soundbite for the Save the NYPL cause.

Zadrozny accidentally became the poster boy for a movement. The photo and its caption was shared and ‘liked’ over 200,000 times on Facebook.

“I’ve never liked having my picture taken,” he tells me by email. He does, however, have a deep love of the library and that love trumped his camera-shyness. “That a member of the public can walk in and work alongside a Pulitzer Prize winner,” he says, “whether to consult the collections or just write emails, is what makes the NYPL, and NYC, great.

The viral power of Zadrozny and his chicken seems to have made a lasting impact. On 7 May, Tony Marx announced that the plans were to be scrapped: “When the facts change the only right thing to do as a public-serving institution is to take a look with fresh eyes and see if there is a way to improve the plans and to stay on budget. That’s why months ago we began a review of all programmatic, design and cost elements of the renovation plan and why we are now proposing an alternative plan that we believe will best meet our original goals.

His statement went on to say: “We are proposing to undertake the most comprehensive renovation in the building’s history, reopening long-closed rooms to the public while leaving the stacks intact.”

It seemed like an outright victory for Save the NYPL. The small print, however, revealed that although the central stacks would remain, the books they have housed would not. This, campaigners agreed, was disastrous. A library that gets rid of its own books, they argued, is a library with a death wish

Asked by New York magazine what lessons he’d learned from the experience, Marx replied: “The primary lesson we learned was that as facts on the ground change, it’s important for an institution to not stand still, but rather keep asking: is this still the best course? I want to make sure we’re institutionalising that across every aspect of this organisation.”

He did not, however, mention transparency. Throughout this whole process, one of the biggest complaints of advocacy groups has been the library’s secrecy with its plans and its stonewalling of inquiries.

“Why don’t they publish the minutes of their board meeting?” demands Bernofsky. “And the finances of their project? Why should that not be public information?

Zadrozny also has questions: “Why is the library›s main trustee – Stephen Schwarzman, the head of private equity firm Blackstone Group – driving library policy while librarians are muzzled and the public is ignored? Why is the president and CEO of the NYPL, Tony Marx paid out of private funds?”

This latter fact was confirmed by the New York Times, who reported that the library’s tax returns showed that Marx earned $781,000 in his first full year as president and CEO.

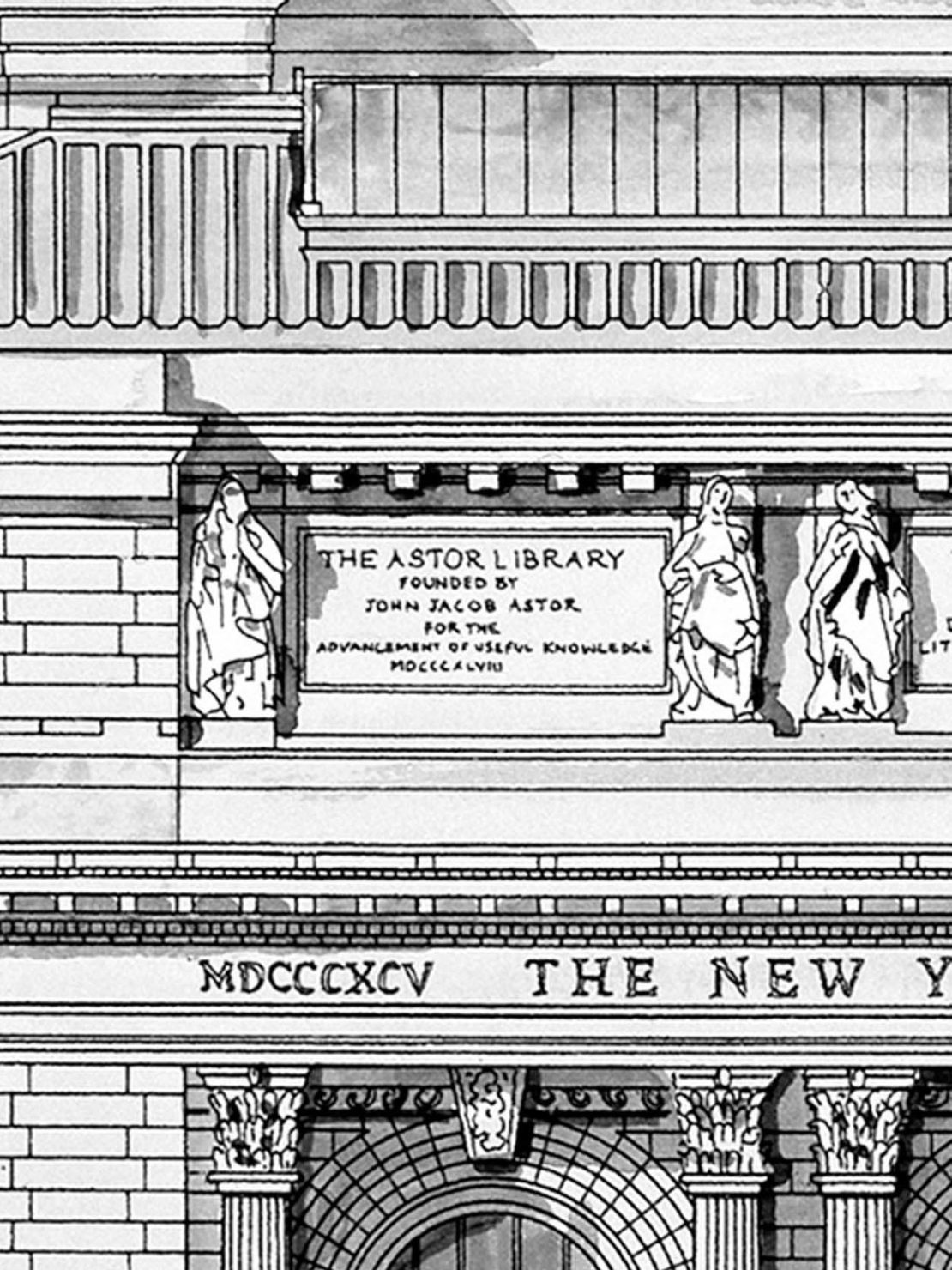

The ‘public’ in the New York Public Library is, it turns out, a somewhat fraught word. The library was born out of the late 19th-century merging of the Astor and Lenox libraries after New York Governor Sam Tilden died and bequeathed his fortune for the purpose. It was decided that the public would retain ownership of the building but that a private charity, named The New York Public Library, would be in charge of staffing, stocking and generally overseeing the institution. Soon after, the steel magnate Andrew Carnegie donated $5.2m towards the creation of a network of branch libraries which ended up being run, not by the city administration, but by the existing private charity. A public-private partnership was formed. The NYPL is thus both a public institution and a private charity, which exempts it from Freedom of Information Acts, exacerbating the frustration of those campaigners, journalists and members of the public seeking information. As Bernofsky puts it, “It’s a supposedly public institution but it’s run as a private charity for which reason its trustees can do whatever the hell they want.”

The first ever request to be filled in the library was placed seven minutes after its opening on 23 May 1911 by David Shub, a 23-year-old Russian Jewish immigrant from the Bronx who was seeking a Russian language book, Moral Ideas of Our Time: Friedrich Nietzsche and Leo Tolstoy. Over three decades of researching, writing and socialising in the library later, Shub published an English language book, Lenin: A Biography. His trajectory from Russian-speaking immigrant to published author via the public library is a heartening story, but it illuminates worries for the would-be Shubs of the future. As Bernofsky points out, by having books off-site and increasing the delivery time from a matter of minutes to up to two days, the library is putting the livelihoods of biographers and other non-fiction writers in jeopardy. “For these people trying to make a living by writing their books in a reasonably fast fashion,” she says, “this is a death knell for some of their careers. A library is a usable museum of books and if you get rid of the books, you'll never get them back again.”

I love this place. I love that you feel that you're part of a bigger picture. You are at your desk writing but there's everybody around you and all kinds of people

Her conclusion is blunt: “This is just a symptom of our country’s selling out,” she says plainly. Evidence, in her view, that “We’re not a democracy, we’re a plutocracy.”

The prevailing argument to dismiss libraries goes like this: in an age of Google Books, e-readers and the digitisation of resources, real books – smelly, paper books, vulnerable to physical decay – are neither viable nor needed. Intellectual and moral arguments aside, the ever-growing figures for library attendance refute that. Last year the NYPL received a record 2.5 million visitors and the NYC-based thinktank Center for an Urban Future reported that in the fiscal year 2011, the city’s 206 public library branches had over 40.5 million visitors, which is more than all the city’s professional sports teams and major cultural institutions combined. Crucially, these are not just visitors but active users; statistics released in the library’s annual report show that the number of items being borrowed is growing too. Between 2008 and 2012, circulation increased by 44.4 per cent.

Among the visitors today is Marilyn Oliva, a 60-year-old writer and academic who is professionally dependent on the library as she’s no longer affiliated to a university. I speak to her on her way into the Rose Main Reading Room.

“I love this place,” she says. “I love that you feel that you’re part of a bigger picture. You are just at your desk writing but there’s everybody around you and all kinds of people and it’s almost like seeing a movie: everyone’s looking at the same thing, having different experiences, and you might be there for different reasons but it’s a communal atmosphere and everyone’s keeping this place going by coming here.”

If only that were true: visitors in themselves don’t fund a library. She’s nonetheless sanguine about the institution’s future. “I think they're trying to move in a direction that’s going to be tough, and I know a lot of people are very mad. I’m not mad; I realise that they’re in a really tough position.”

Down in the vast marble lobby Rustum Romaniuc, a Moldovian graduate student studying the history of economic thought, is sitting on a bench checking his phone. He’s here partly as a tourist, he explains, and partly to work.

“This is an amazing place, it’s not just a library but a historical place,” he says. I ask him if he’s aware of the plans and their controversy. He’s not, so I fill him in.

“That would not be a good thing to do,” he frowns. “In my opinion America is already too commercial. There are so many commercial places so it’s good to have a New York place that’s not commercial.”

Outside, I take a closer look at the famous lions flanking the entrance. Patience presides over the southern side of the entrance and Fortitude over the northern side. The names suit them. They may be lying down, but their upright, stiff heads have the proud carriage of sentinels who take their duty seriously. They look unassailable, immutable as you’d expect enormous lions cast out of marble to do. The humans running the library, however, have a more difficult job: remaining flexible in a time of renewal and change.