Back up plans

What’s the best way to move backward as a society? That’s right: backward, not forward. If the question needs clarification, that's because it’s not often asked. We’re constantly urged to innovate and look forward but looking back is positively discouraged, deemed dangerous and unsavoury. Our resolve to learn from history is all but forgotten: with the pace of change accelerating all the time, innovations seem to render old models of thought and behaviour obsolete – even the recent past has barely any relevance to the present.

In this atmosphere, only the most reactionary conservatives waste precious seconds looking back for solutions. Type ‘bring back’ into Google and the auto-complete suggests ‘the death penalty’, ‘corporal punishment’ and ‘national service’. But despite the urgent moving on, our society is facing a set of distinctly retrograde problems and challenges. In Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty uses new evidence of rising inequality to describe our time as a second Gilded Age, rivalling the late 19th century in terms of income inequality. Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson’s book The Second Machine Age suggests that advances in computing power could mean we are entering an era of ‘technological unemployment’ reminiscent of the early days of the industrial revolution. Alongside that, the austerity of the 30s, the housing shortage of the 50s and the energy crises of the 70s are repeating themselves. If ever there was a time to look back and seek solutions from history, you’d think it would be now.

The central part of Croydon Tramlink runs in a loop, from East Croydon to West Croydon via Church Street, then ending up back where it started. For trams in general, this is a familiar trajectory. In the 50s and 60s trams were ditched in favour of buses and cars. When the last tram trundled out of London on 4 July 1952, 20,000 cheering people turned out to watch it leave, in “a send-off the American President might envy,” as a contemporary documentary put it.

And that, it was fair to assume, was that. Except that 30 years later, trams made a comeback, often in the same places they had been removed from only a generation before. Birmingham, Manchester, Sheffield, Newcastle, Nottingham and Edinburgh, have all rebuilt their tram systems. Today, Croydon’s Tramlink takes passengers on more than 30m journeys a year, while the national figure is more than 200m. As cities across the world struggle to deal with congestion and pollution, a light rail renaissance has seen France go from three tramways in 1985 to 25 today.

Trams made a comeback, often in the same places they had been removed from only a generation before

Shanghai, Adelaide and New Delhi plan to rebuild old systems; and even car-loving America now has 30 cities with tramways.

In the private sector, companies are profiting by reviving old technologies and business models. Swiss wind-up watches were surpassed in the 70s by digital alternatives, forcing manufacturers to redefine their product as a luxury status symbol rather than a tool for telling the time. The strategy was so successful that the mechanical watch industry is now Switzerland’s third largest source of exports.

Artisan brewing was almost dead in Britain by 1970, with styles such as porter washed away in a sea of lager, but today there are over 1,000 breweries in the UK, more than at any time since the 40s. Updated versions of old technologies are being used to revive a style of brewing that had almost become extinct. “There are new ideas going into the whole microbrewery revolution, but the picture it’s creating is one that looks like brewing used to look in the 19th century,” says beer writer Pete Brown.

Spurred on by emission curbs and the cost and difficulty of acquiring fossil fuels, trams aren’t the only form of outmoded transport being revived; balloons, electric cars, bicycles and sails on cargo ships are also making a comeback. “This is old technology,” says José Mariano López-Urdiales, CEO of zero2infinity, a company that wants to use helium balloons to take tourists into space. “It’s been possible for decades. It hasn’t been done because of the way we allocate capital, the way we count beans.”

Technological development is supposed to run forward in straight lines, yet more often it travels in circles. Despite our reluctance to cast our eyes backwards, we are happy to rediscover old technologies when they become useful. The mistake we make is to be fooled by the promoters of new technologies into seeing technology only in terms of invention and innovation. Take, for instance, three tools: smartphones, forks and sandals. For some reason only the least widely used – so arguably the most dispensable of these – is ennobled with the title ‘technology’.

Explore

Good ideas that didn't pan out, part 1: free money Good ideas that didn't pan out, part 2: Project CybersynIn The Shock of the Old, the historian David Edgerton argues that our infatuation with novelty and the future hampers our search for meaningful social solutions. We consistently overrate the impact of dramatic innovations and inventions, yet take from each failure the lesson that next time will be different. The steamship did not bring about world peace or break down the barriers between nations. Nor did the railway, the machine gun, the aeroplane, the radio or the atom bomb. Neither did the internet. “This word ‘technology’ turns us all into idiots,” Edgerton tells me. “People should think about the future and they should want to move to a future that’s different from the present; but people should create those futures by looking in other places in the present and by looking at the past.”

Scientific and economic dogma holds that ideas exist in a meritocracy. The most useful ideas, from the wheel to the second law of thermodynamics, survive because they are better than their rivals. There are no mistakes. If an idea should have been brought back, it would have been. Yet the history of energy supply shows this is not always the case.

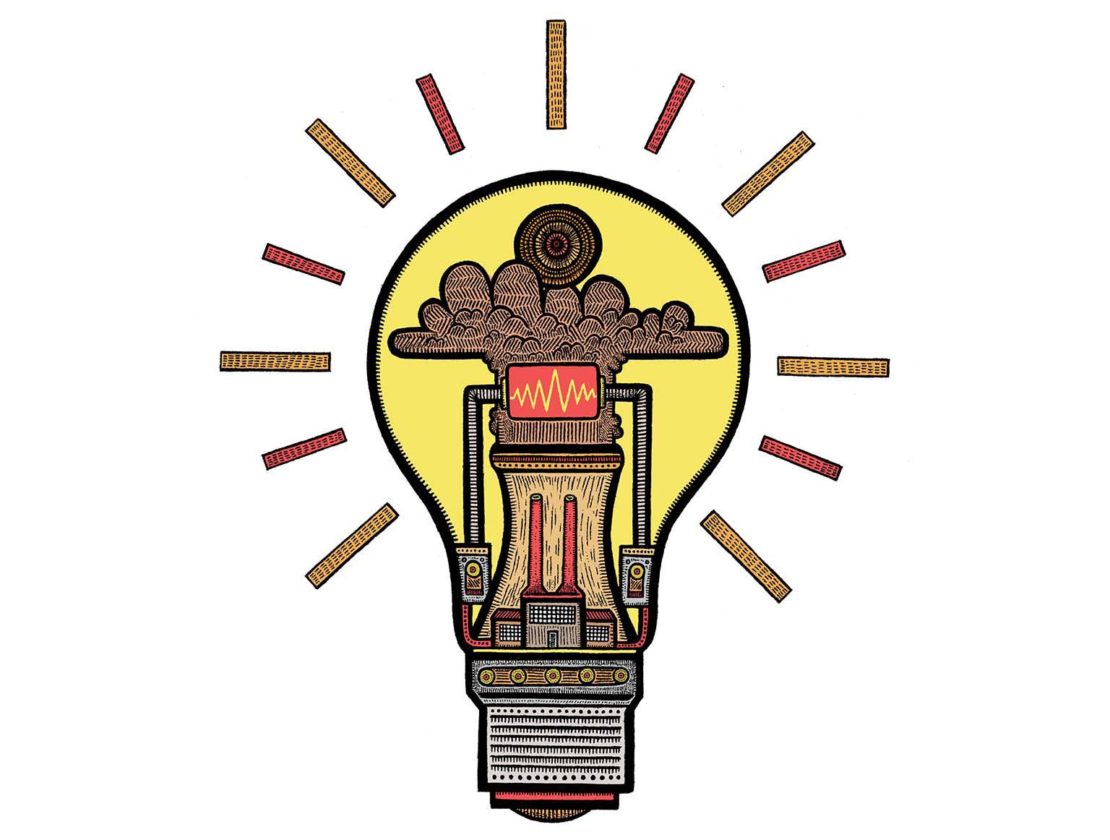

Britain’s energy sector could be about to have its own Back to the Future moment. I went with Felix Wight, head of development at Community Energy Scotland, to inspect a disused combined heat and power (CHP) plant on a rundown estate in south London. CHP plants are power stations which produce heat as well as electricity. Run the right way, Wight tells me, they can cut both cost and carbon dramatically, by using the excess heat produced during electricity generation to warm the homes of nearby residents.

Popular before the war, CHP power stations were discarded afterwards as electricity generation moved out of cities and into remote locations that made the capture and transmission of heat uneconomical. But two London councils, Hackney and Islington, recently replaced their old gas- and oil-fired boilers with cheaper, greener CHP plants, which are predicted to to cut energy costs by up to £2,000 per resident. At a time when household energy bills are rising by five per cent a year and over 30,000 more people are dying in winter than in summer, this is a potentially life-changing, even lifesaving, revival.

Britain's energy sector could be about to have its own Back to the Future moment

For the energy sector as a whole, the true potential of CHP is not the technology itself, but the way it is used. In the early days of electricity generation at the end of the 19th century, small electricity networks were set up as private enterprises. These were joined by borough authorities in cities such as London and Manchester until, by the 30s, electricity was generated and supplied by as many as 300 private and municipal power companies. Then, in 1948, the energy market was nationalised, and 300 were effectively reduced to one, an agglomeration scarcely reversed in the 90s when liberalisation introduced the giant energy companies known as the ‘big six’.

Now local energy could be on its way back. In May, the Greater London Authority announced it was applying for a permit to become a local electricity supplier. Under Licence Lite, the GLA would be able to buy excess electricity from small generators in London and sell it to public sector bodies such as the NHS and the police. Councils in Bristol, Aberdeen, Slough and Merton have all made moves to introduce district heat and power projects. “Theres quite an excitement in this community,” Matthew Pencharz, the Mayor of London’s senior adviser for energy and the environment, told BBC Radio 4. If the GLA’s plan succeeds, Britain’s energy industry will have gone from private to municipal to national ownership, then back to private, before returning to municipal.

Given the inertia of the energy sector, this is still a big if. “There’s a long way to go,” says Felix Wight of CHP’s comeback. Once a system is in place, it sets the parameters and everything else has to fit into it. This pattern of institutional entrenchment, driven by companies with a vested interest, is a force even in the most apparently dynamic industries. Ben Greenaway, a software developer, told me that few developers working nowadays understand what makes the system work as a whole, because they only work with ‘the products on offer’: the apps and plug-ins produced by Apple and Google. (Greenaway advocates bringing back the ‘Ready’ command prompt: in other words, he would bring back computers that forced us to learn code.)

Looking at technology as it is actually used can help free us from the idea that there are rules to technology aside from the ones we make ourselves. There is no law which decrees that technology has to advance, that a new technology definitively displaces an old one, or that we have to adapt to new technology or fall behind forever. There is always an alternative, even when everyone is saying there isn’t.

Faced with similar energy supply challenges, other countries took different paths. In Copenhagen, 98 per cent of heating is supplied by district heating networks. In Germany (where, incidentally, trams were modernised rather than destroyed after World War II), there are more than 1,000 electricity supply companies and small suppliers occupy over 50 per cent of the market. In the history of the British energy sector, the apparently irrefutable technical case – made first for nationalisation, then privatisation – appears less important than the belief that this was the way of the future. Edgerton calls this blind faith “futurism” which “stops us thinking in a grown-up way.” By looking back we can rescue ideas from the tides of fashion.

Where does this faith in the future come from? In his book Futures Past, historian Reinhart Koselleck argued that we lost our sense of historical continuity in the second half of the 18th century. Enlightenment rationalism, mercantile capitalism and early industrial revolution combined to create a myth of progress that split the past from the present and created a pervasive ideology of futurism.

In effecting a revival, few forces are as potent as nostalgia which may actually be enabled by a disjuncture from the past. One of the common features of many revivals is the small group of diehards that sustain an idea in wilderness, like the veteran employee who saved one Swiss watch manufacturer’s moulds by taking them home and hiding them in his shed. For British trams, it was the Light Rail Transit Association. The Campaign for Real Ale kept the flame of artisan brewing alive during the lost decades. Now it finds itself in the role of reactionary defender of the faith, resisting the introduction of new methods that may prevent microbrewing dying out a second time. One brewery founder told me that CAMRA was ‘doctrinaire’ and “trying to impose an old-fashioned method of beer production”; and that he would lose his membership card if it found out what he was saying.

Nostalgia may appear to be the inverse of futurism but, as historian Christopher Lasch notes, it is more like its ideological twin. Like futurism, the word nostalgia is a modern creation, first used by a 17th-century Swiss physician to describe the listlessness of soldiers who longed to return home. Nostalgia looks at the past solely from the perspective of the present. None of this makes it a very thoughtful guide to action. Writing on the return of trams in Los Angeles, Robert Post suggests that myths of 'LA’s bygone trolleys' – such as the conspiracy theory that General Motors and other interested parties bought out the system in order to dismantle it – were used to create the false impression that trams had died an unnatural death. “Such imagery,” Post writes, “entwined as it was with the emotional intensity of nostalgia, was quite sufficient to begin colouring political ideology,” with the result that trams were brought back at great expense for the benefit of developers and wealthy white suburbanites. As Stephanie Coontz notes in The Way We Never Were, it was nostalgia for a rural idyll that never existed that powered the development of suburbs, which in turn brought back the motor car.

To see the twin forces of futurism and nostalgia in action, we only have to look at branding and marketing, where an obsession with innovation is sometimes offset by the urge to bring things back. Brands such as Coca-Cola and Cadbury revive elements from their own pasts; Hollywood ‘reboots’ old films and churns out sequels; even local councils have been known to get in on the act, as Boscombe in Dorset did recently with a Doctor Who-inspired police box. There is nothing that stops reappropriation being heartfelt and creative, yet it is hard to escape the suspicion that this is bringing things back for the sake of it. The Dorset police box will be staffed “as much as is operationally possible” during shop opening hours. It is not a functional revival but “a fantastic, iconic symbol”, a “highly visible policing footprint” intended as a tourist attraction. Rather than opening up the past for use as a resource, the nostalgia industry closes it down by presenting history in its packaged, idealised version. The past and future are treated as brands; and there is something closed and airless about the world of a brand, like a town that only exists for tourism.

I asked a lot of people what they would bring back. Everyone had an opinion – well, almost everyone. The beer writer Pete Brown said that he couldn’t tell me what he’d bring back “because it might be a business idea”. Dave Coplin, chief envisioning officer at Microsoft UK, found it impossible to envision the question: “For some reason it just doesn’t compute with my way of thinking.” Most people, though, were happy to oblige. Among the many suggestions were: old varieties of fruit and vegetables, midwives, small arable fields, co-operatives, comprehensive regulation of financial industries, youth culture, county cricket festivals, O-levels, handwriting, a preference for phone over email, Psion-style keyboards for smartphones, the study of rhetoric in schools, unisex toys and female pubic hair. Also: manners, chivalry, trust, fatalism, honour and Christianity. “Is it possible to revive it and slough off all its horrible Anglican associations, at least as a moral code?” asked the philosopher Robert Rowland Smith.

There is always an alternative, even when everyone is saying there isn't

That was the problem with these large, abstract concepts. Each one was an entire system of thought: to bring back part, you would have to resuscitate the whole. Picking and choosing – chivalry without gender inequality, trust without social stratification, honour without revenge, Christianity without God – wouldn’t really work. And the practical difficulties seemed insurmountable. How do you start bringing back a worldview?

Several people wanted to bring back customs and rituals. One woman, a widow, suggested bringing back specialised clothing for mourning. “It would be so much easier if everyone knew,” she said. As a society, we have become under-ritualised. We have no way of marking many significant occasions in our lives, although studies repeatedly state the psychological benefit of being able to do so. But even if we could decide which ritual or custom to revive, who would do the reviving? By what mechanism would they act? The state, the one body which might be able to, is the one body that shouldn't. Religious institutions and the market were equally unappealing candidates. This is the trouble with turning the clock back. Who does the turning? What time are they turning to?

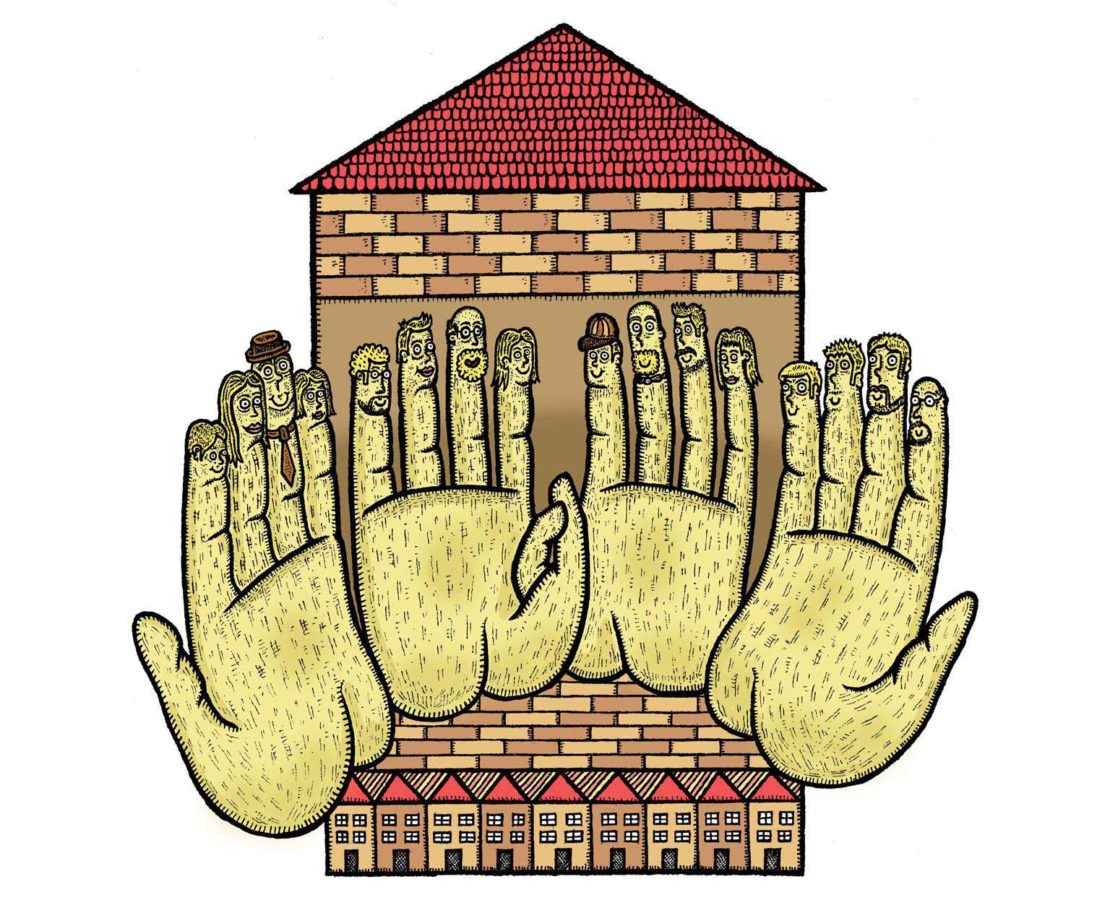

Lenin’s fundamental political question ‘Who? Whom?’ sums up the central problem with the current revival of garden cities: first conceived 100 years ago by Ebenezer Howard, they are all the rage as the housing shortage becomes politically urgent. In March, George Osborne announced the creation of a new garden city in Ebbsfleet, with up to £200m in public funding. A prize of £250,000 has been offered by the Conservative peer Simon Wolfson for the best answer to the question: “How would you deliver a new garden city which is visionary, economically viable, and popular?”

Three people suggested bringing back garden cities or new towns, for three entirely different reasons. The difference in each case was the question of authority. For Rory Olcayto, acting editor of the Architects’ Journal, new towns represented a bygone era of state-sponsored artistic freedom. For Philip Ross, founder of the New Garden City Movement, the key principle was community land ownership. Miles Gibson, director of the Wolfson Economics Prize, proposed a completely opposite “old model of maybe slightly patriarchal, philanthropic investors” such as the Duke of Westminster or the Grosvenor Estate. The notion of a revival serves to obscure the seemingly unbridgeable divide between the idea’s various supporters. Meanwhile, for the government, the popularity of garden cities is more important than any sense of what the end result should be. The appeal for them is the garden city as a brand.

The sense that large, impersonal forces had changed things for the worse was the motivation for any number of suggested resuscitations. Simon Stevens, the new head of the health service, suggested recently that the NHS bring back cottage-style hospitals in order to treat patients in their local communities. “Most of western Europe has hospitals which are able to serve their local communities, without everything having to be centralised,” he said. If the culprit here was over-zealous, mass centralisation, then elsewhere it was market forces, in the form of performance-driven, individualised working – especially in the public sector. Alison Smith, a nursery school headteacher, wanted to revive non-assessed activity in the public sector, a thought echoed by Edgerton: “It was a very good thing to have governments that were concerned with the good of the community as a whole rather than following performance targets.”

The common theme of these conversations was the sense that the market was too rapacious to be trusted and the state too weak and cowardly to restrain it. In the case of football clubs, the state meant the Football Association. The author Richard Benson wanted to see the return of clubs with a moral and social purpose. “Fan-owned football clubs benefit more than just fans,” he said. Barcelona and Real Madrid are both fan-owned; so, by law, is every team in Germany. In Britain the original Football Association regulations ruled that clubs should not be run for profit, a stipulation which survived until the 90s, when the FA allowed clubs to be turned into companies intent on the enrichment of their shareholders. Describing this shift in his book Richer Than God, the football writer David Conn laments “the year zero attitude to football’s development” and blames the businessmen for their greed and the FA for allowing them to get away with it. A number of groups of fans are trying to bring back member-owned clubs, the most successful example being Swansea City, a trophy-winning, 20 per cent fan-owned Premiership club. Yet such radical change seems possible only when a club comes close to ruin. The Manchester United fans who campaigned against their club’s debt-financed sale in 2005 were forced to turn elsewhere to found their own fan-owned club, FC United, which resides in the lowest reaches of the league.

We can stop thinking about 'technology' and start thinking about the things we use

Lacking a clear sense of who should do the bringing back, people found it difficult to propose revivals with conviction. Ideas came prefaced with disclaimers: “It’s impossible, but…” or “It wouldn’t happen now.” Ray Auker, chairman of the Anglian Potters Association told me he would bring back craft guilds, the main form of professional association in the middle ages (and which the sociologist Richard Sennett suggests may be returning in the groups used by developers of open-source software). Yet even as he made his suggestion, Auker felt the need to apologise for his “grumpy old man’s ramblings”.

The music journalist David Hepworth wanted to bring back the days when bands played more than one ‘house’ a night. "Won’t happen, of course,” he added, “because the current system suits bands, who don’t care about customers.” Perhaps it was the way I posed the question, but it seemed to me that people felt detached from the past by the sense that the process of change was out of their hands.

It is possible to reach back into the past in a way that is both optimistic and realistic about the possibilities of change. In 2008, Paul Hocker, play development manager at the charity London Play, was researching street parties in the British Library. “I typed in the wrong word,” he says. “I put ‘play street’ instead of ‘street play’ and this stuff came up from the 30s and 40s about streets being shut to create temporary playgrounds.” The practice had died out – killed by the same army of cars that killed the first generation of trams – but the legislation still exists, and London Play have been able to use it to bring back play streets in 12 London boroughs.

Last year, the regeneration agency Spacemakers revived public space in the London suburb of Cricklewood by touring a tiny mobile town square round the area for a month, pausing on forgotten patches of land to reclaim them as public spaces. “If you try to bring stuff back people just think you’re being nostalgic,” says Spacemakers director Matt Weston. “What we wanted to do is prove it works, almost prototyping on a small scale, rather than just arguing for public space, because you're not going to win that argument.”

What can we do to encourage this kind of revivalism? For one thing, we can cherish variety. That means not being too quick to get rid of things or bring in wonderful new solutions that require the destruction of what the American political philosopher Bonnie Honig calls “objects of public love”.

For another, we can stop thinking about ‘technology’ and start thinking about the things we use. There is so much we can do with our existing tools, but some interpretations of ‘innovation’ can dispense with the past and suck the energy from the present. Progress is a compulsion: we have to be moving forward. But it can still be achieved by looking back.