For what it's worth: a visit to the People's Bank of Govanhill

"Who's got emotional work?", Sarah Turner asks, leaning over to get a stamp while women imprint different symbols on to a paper tablecloth. Turner works for The Well, a multicultural resource centre in Govanhill, a district of Glasgow where as many as 50 languages are spoken. Today some of the women involved with The Well have joined with other community groups in Glasgow to talk about their paid and unpaid work. Many of them do 'emotional labour', like caring for children or elderly relatives, without really considering its economic value.

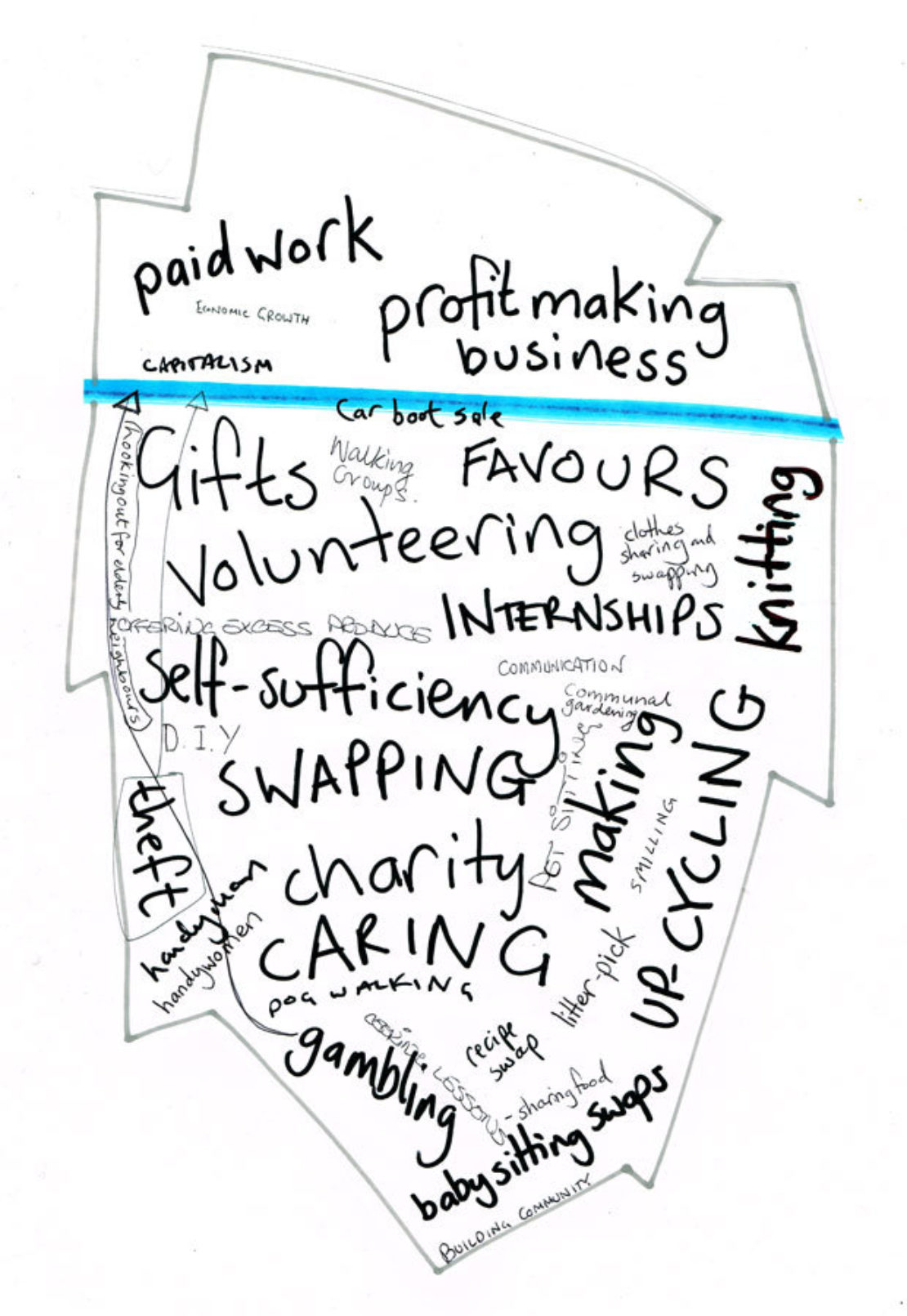

Ailie Rutherford, the artist who organised the meeting, is at the other end of the table drawing a picture of a sewing machine on to the bottom half of a cardboard model iceberg. Rutherford borrowed the iceberg concept from feminist political economist duo JK Gibson-Graham as a metaphor for the many alternative economic exchanges that take place under the surface in Govanhill, where community and faith-based transactions are often not valued in terms of hard currency. The sewing machine is to symbolise the unpaid work of mending clothes, at the suggestion of one of the Pakistani women.

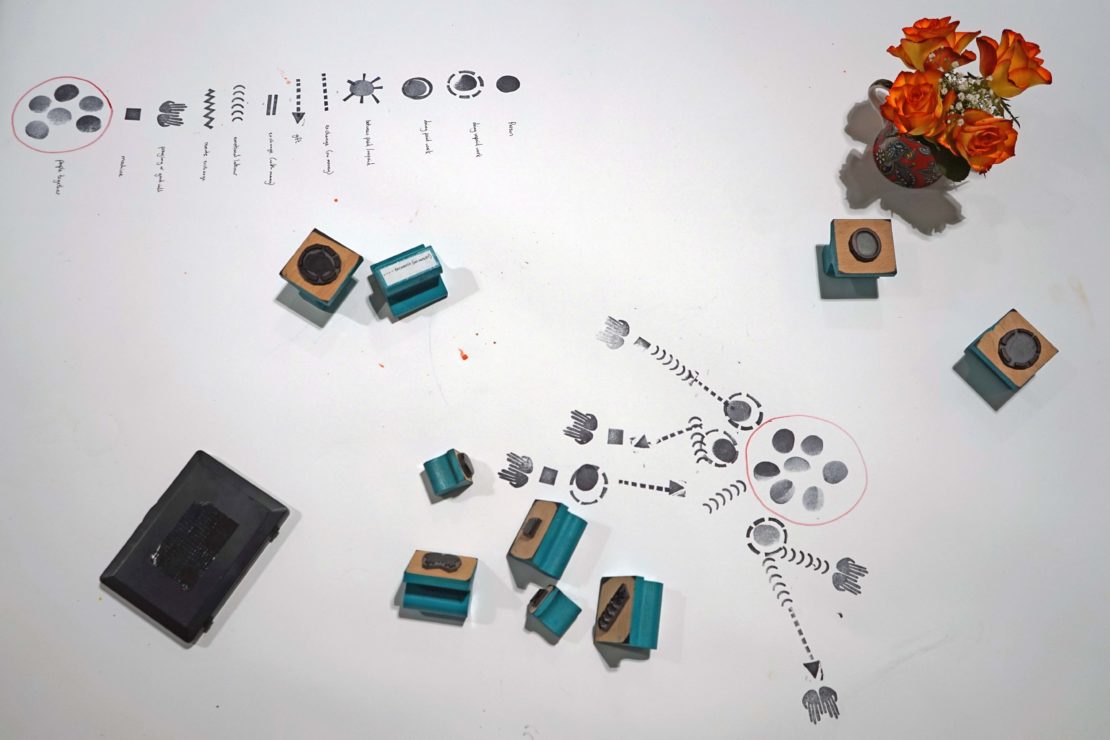

Collating and mapping the work of such people with ink stamps and drawings is just one of the ways Rutherford gets people to think about alternative economies as part of her art project, the People's Bank of Govanhill. Another is by circulating a currency whose value changes every time it is used. The 'Govanhill notes' are designed as a voucher system for non-monetary activity. Today, Rutherford hopes to learn from the women what kinds of activities that might include. The meeting itself is already based on one kind of exchange: each of the women has brought a dish to share with the others for lunch.

Back at the other end of the table, a British woman called Pam inks a stamp of two hands on to the iceberg to signal goodwill, or religious work, and links it with a dotted line to a black mark that represents her. "That's for when I pray for my daughter, who lives in New Zealand," she says.

Next door, a group of Roma women speak quickly in their own language, drawing a web of lines between the black spots that represent them. Lamiita Covaci, one of the English-speaking women, explains to Rutherford that they do unpaid work for one another all the time, looking after each other's children, taking relatives to the doctor and running busy households, often on top of paid jobs.

"I like to help the people and I like to work. No money, but anyway I like to work. When I'm doing something I am happy," she tells Rutherford.

Helen Macleod, a Roma project worker, watches the women explaining their routines with a big smile on her face. Macleod is one of a handful of recent employees at The Space, a new venue set up to welcome women, including Roma, for classes and groups. Just a moment ago, everyone introduced themselves by name to the room. Some of the Roma women at the table had only learned how to say "my name is" in an English class a few hours earlier.

Sign up to our newsletter

"A lot our ladies have been ostracised from communities, they've been looked down on, treated in such a way that they might feel negatively about themselves, or about other groups of people. Some of them will never speak to anyone outside their community," Macleod says.

Govanhill is popular with immigrants partly because of the area's many private landlords, who may not abide by laws regarding overcrowding that prevent children of the opposite sex sharing a room past a certain age, for example. Macleod says these private landlords sometimes draw tenants into contracts where they might live above a restaurant and also work in that restaurant. The contracts might be for 22 hours a week or fewer so that the workers can qualify for working tax credit. But the tenants might actually work up to 60 hours a week, for 22 hours' pay, which works out at as little as £2 an hour.

Macleod says this is may be a huge improvement on the previous circumstances of many of the women she works with. "It's a very difficult life. If you don't have an education, if you don't have a job, if you're shunned by your society, if you're looked at in a certain way, every day is about survival," she says.

"They would see it as they haven't had this before: I have a house, a roof over my head, some money and my children are in school. What they don't see is their self-worth in the same way."

Part of Macleod's work is showing the women that they have a right not to live in a house with cracks in the walls, or mice, or bedbugs.

More in this series

The cooperative bakery reviving Anfield The Scottish village that bought its harbour New money: Do local currencies actually work?"If you ask them, they will tell you they are nothing. They have high hopes for their children, but they don't see their own worth. They don't value what they do or who they are," she says.

One way to change that is to recognise the work they do, even if it is unpaid, and to show how it contributes to the wider economy. Covaci has done all sorts of work, paid and unpaid, and saved enough money to help her mother join her in Glasgow, where they hope to have a better life than they had in Romania.

She had originally planned to make pakoras for the lunch, but her mother balked and said she must instead make a traditional Roma dish. Her mother had to go home after the English lesson, to look after Covaci's daughter. But she's used halal meat in the Romanian dish so that the Muslim women can try it. They are delighted, some saying it's the first time someone from outside their community has cooked for them with halal meat.

Over tea and homemade cake, Covaci explains to the Pakistani women how to make the dish with braised meat, rice and cabbage. They listen carefully and ask questions about spices. As Covaci talks, one of the women takes the cardboard iceberg and writes a few words beneath the waterline, first in Urdu and then in English: recipe swap.