Dance moves: Riots in Lagos and the birth of electro

The most important dance music release of 1980 wasn't a record, but a box of circuits and wires called the Roland TR-808 Rhythm Composer.

The 808 wasn't the only drum machine in those days – the Linn LM-1 Drum Computer was also released in early 1980. Pop artists like Michael Jackson and, in particular, Prince would conjure stuttering rhythmic magic out of its faders and pads.

There was particular hype around the LM-1 because it was the first drum machine to use digitally sampled sounds from real drums. Until then, drum machines could only crudely imitate percussion sounds by manipulating bursts of white noise or sine waves.

This was high-end studio gear, however, for high-end studio musicians – and, at a fifth of the Linn's retail price, the 808 was more accessible and edgier. A big part of the 808's appeal was its ability to create booming, low-frequency bass drum sounds that sounded awesome in clubs.

In 1980, no other music sounds like Riot in Lagos. In 2016, still barely anything does

Contrary to the movement of music technology at that time, the fact that the 808 didn't really sound like a live drum set did not diminish the machine's appeal; instead it lent its own unique character to any recordings that it appeared on. It just sounded cool.

Roland is a Japanese company and the first exponents of the 808 were a Japanese group, Yellow Magic Orchestra, who integrated it immediately into their set-up. YMO leader Ryuichi Sakamoto showcased the drum machine heavily on his 1980 solo album B-2 Unit, and its lead single, Riot in Lagos.

In 1980, no other music sounded like Riot in Lagos. In 2016, still barely anything does. Still, Riot in Lagos prefigured a lot of major trends in late 20th-century dance music.

In the next two years, more music would arrive that was driven by drum machines and adorned with synths. Purely electronic club music. But most of it came from the States – from Detroit, Michigan.

Sign up to our newsletter

The people who made this music were young, middle-class African-American men. They liked P-funk, but perhaps even more than P-funk, they loved British synthpop: Depeche Mode, Tubeway Army and Visage were staples at Detroit clubs and parties, particularly those featuring the DJ duo Deep Space Soundworks: two college students named Juan Atkins and Derrick May. They really liked Kraftwerk.

With Yellow Magic Orchestra so often regarded as the Japanese Kraftwerk, it's entirely likely that Atkins, May and their crew heard Riot in Lagos and got a few ideas. But rather than being the focal point of a new movement, it's probably more likely that the Sakamoto single was a fluke glimpse into the future.

In 1981, Atkins released the first of his own attempts at music, under the name Cybotron. Cybotron's Alleys of Your Mind single was a thinly veiled recycling of an Ultravox song called Mr X, from their Vienna album. It was much cooler though, and totally geared towards bassy Detroit sound systems rather than chic Parisienne cafes.

This dialogue between synthy European art-pop and bass-hungry Yank club noise wasn't a one-off. In 1982, Arthur Baker twisted two separate Kraftwerk songs and an 808 into a new piece of music, with Afrika Bambaata delivering an afrofuturist sermon over the top; Planet Rock was a milestone in both dance and hip-hop culture, and sampling's first true statement.

A year later, Cybotron hit back with Clear, their dancefloor anthem, and again the music was powered by a loop from Kraftwerk. This music – totally electronic and simultaneously somehow both funky and android-stiff – became known as electro.

"George Clinton and Kraftwerk stuck in an elevator," is how Derrick May famously summarised the electro sound.

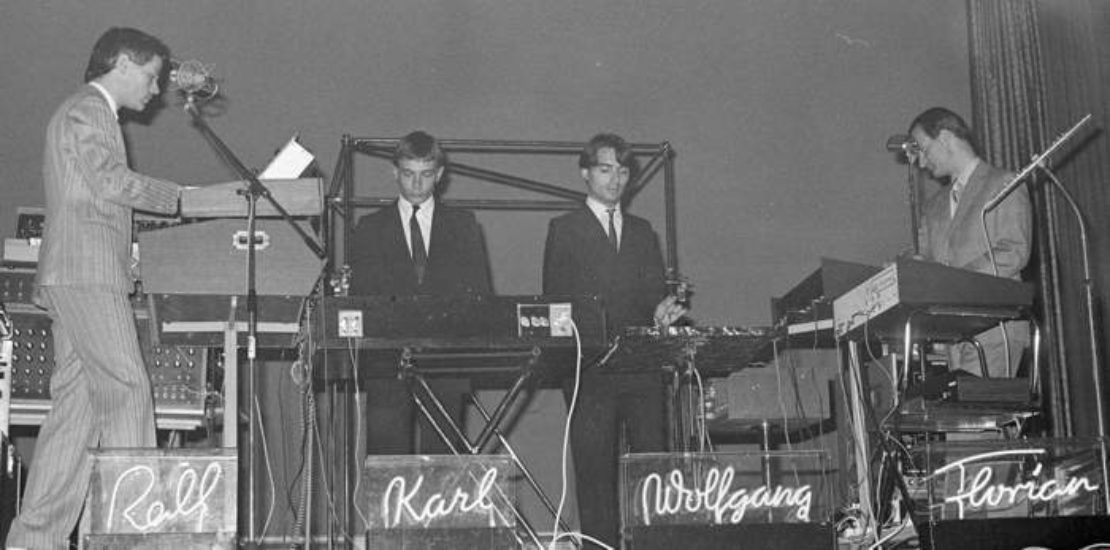

Though George Clinton's contribution to dance music until this moment had been immense, Kraftwerk's influence had thus far been unheralded. They weren't a new group, either – they'd been playing around Germany since the late 1960s.

So why are Kraftwerk suddenly now a driving force in the evolution of dance music? Their 1970s albums are all classic works, but you'd struggle to find a genuinely danceable moment on any of them. Ornate 20-minute hymns to the autobahn and a clever aesthetic that mined a sort of prewar vision of the future, sure, but bangers? Nah.

There's something appropriate about how it took a song about numbers to make Kraftwerk dance

The main thing Kraftwerk brought to dance music was synthesisers. No other musicians until then had embraced synths and investigated them forensically to the degree that Kraftwerk had. Synths were difficult to use and expensive to buy, but in Kraftwerk's world they were important for their connotations of industry, machines, labour and the future.

This aural metaphor was also extremely powerful, musically. It was only a matter of time before someone retro-engineered that sound to make it danceable. The amazing thing is that it was Kraftwerk themselves who did this.

Around the same time as Alleys of Your Mind, Kraftwerk released their masterpiece, Computer World. It is their album-length poem imagining how numbers and data will create new economies and cultures; how having a computer in every home will change things. Kraftwerk's songs are now short and painfully deliberate, and the album's centrepiece, Numbers/Computer World 2, is genuinely as brilliant a piece of dance music as any that you'll encounter.

There's something appropriate about how it took a song about numbers to make Kraftwerk dance. Their percussionist, Karl Bartos, was classically trained and some critics have suggested that his conservatoire-level studying of instruments like marimba and xylophone provided a perversely good training ground for the machine-logic of early 1980s rhythm sequencers.

It is rhythm that frees these pieces from conceptualism. In Bartos's too-clever percussive patterns he tastes the transcendence of what dance music could offer. In Numbers, a simple five-note drum sequence is sprinkled with micro-beats – tiny winged-things – that flutter around an elastic, pinging flange on the snare and bass drums, which in turn forms a kind of implied bassline. Full of hallucinated not-there moments while still crammed with architectural detail, the piece gives the impression that it is fluctuating constantly while remaining mathematically and reassuringly precise – a weird rhythmic attribute that wouldn't achieve genre-form until the turn of the millennium with microhouse.

Most read

Why the world wide web will break up Is there such thing as a 'criminal' face? Are women the answer to our uncertain political times?Kraftwerk would only release one more studio album, before transforming into a kind of self-repairing museum exhibit. But the musicians they had inspired were only just getting started.

These days group founder Ralf Hütter talks earnestly of a 'spiritual connection' the Dusseldorf group had with Detroit, and fondly remembers being taken clubbing there by Juan Atkins and Derrick May. It's a sweet acknowledgement of a sort of symbolic passing of the torch.

The electro fad that encompassed Planet Rock, Cybotron and Computer World was a short-lived musical moment, but it provided a template for electronic dancing music. Its twin child genres, techno and house, dominate dance music to this day.

Techno was a pure refinement of electro's science fiction leanings and post-human surrender to quantised machine rhythms, while house gleefully shed that stiffness for a soulful bounce and party-appropriate funkiness.

Of the two, techno had the longer and slightly more painful gestation. Its first single could be Sharevari – a comic send-up of early 80s Detroit scenesters that, in its instrumental version, formed a brilliant, bluntly aggressive dance track. The single was credited to 'A Number of Names' by the Detroit DJ the Electrifying Mojo, as its authors hadn't thought to present the track with any identifying information.

The Detroit Metro Times commented of Sharevari that it sounds like multiple records being mixed, suggesting that it was Detroit's first record to respond to what the DJ added to the music.

Juan Atkins firmly denies that Sharevari came out before his own Alleys of Your Mind. He alleges that A Number of Names didn't release their track for another year, sneakily adding '1981' to the label in order to snatch some retrospective credit for Cybotron's new sound.

Whatever, this music was now altering its composition to respond to changes in how that music was being disseminated and enjoyed. In a new feedback loop that featured the club, the DJ and the producer in some eternal uroboric three-way, the way music was structured was now being informed by how people wanted to dance to it.

So, Sharivari might be the first techno single, but between its release and 1987 there was only one person in the world making techno music, and that person was Juan Atkins. By the middle of the decade, Atkins had retired Cybotron and devoted himself single-mindedly to the pursuit of a melodic but technology-driven music made for clubs. Released under the name Model 500, his classic singles during this period are the very foundation of techno.