Dance moves: How swing became the first pop music – and gave us the first hipsters

As Louis Armstrong once explained on Bing Crosby's radio show, "Ah, swing, well, we used to call it syncopation – then they called it ragtime, then blues – then jazz. Now, it's swing. Ha! Ha! White folks, yo' all sho is a mess."

Swing – much like our recent instalment in Dancing music in the C20 on big band jazz – was a contentious development in the genealogy of jazz. Swing does indeed follow the same categorical evolution as charted by Armstrong, from ragtime to blues into jazz, but where Armstrong – in his genial openmindedness – considers all of these divisions to be fundamentally the same core music, the jazz elite reacted to the runaway popularity of swing with scorn.

Swing changed the direction of popular music. Its boom years of 1935 to 1945 are the high watermark of the general public's tolerance of jazz which, prior to swing, had been messy, noisy, rulebook-shredding stuff; and, post-swing, returned to restlessly innovative – but less danceable – forms via bebop and its infinite offshoots. These years also saw the recording industry come into its own as a cultural force, although the Great Depression had significantly reined in the industry's ability to realise its potential as the economic powerhouse it would become.

Swing was the recording industry's first child: the first dance music to be born within the mass public's consciousness; and disseminated via technology rather than orally

Nevertheless, swing was the recording industry's first child. The growing popularity of records as a way to experience music meant that this was the first dance music to be born within the mass public's consciousness; and disseminated via technology rather than orally, as folk music, as early American music forms had been up until then. Alongside MGM musicals – for which swing provided a symbiotic soundtrack – swing offered a gaudy, energetic and generally positive antidote to the reality of the already-crumbling American Dream, which had been identified in James Truslow Adams's 1931 book, Epic of America, as:

... the American dream, that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for every man, with opportunity for each according to his ability or achievement. It is a difficult dream for the European upper classes to interpret adequately, and too many of us ourselves have grown weary and mistrustful of it. It is not a dream of motor cars and high wages merely, but a dream of social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable, and be recognised by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position.

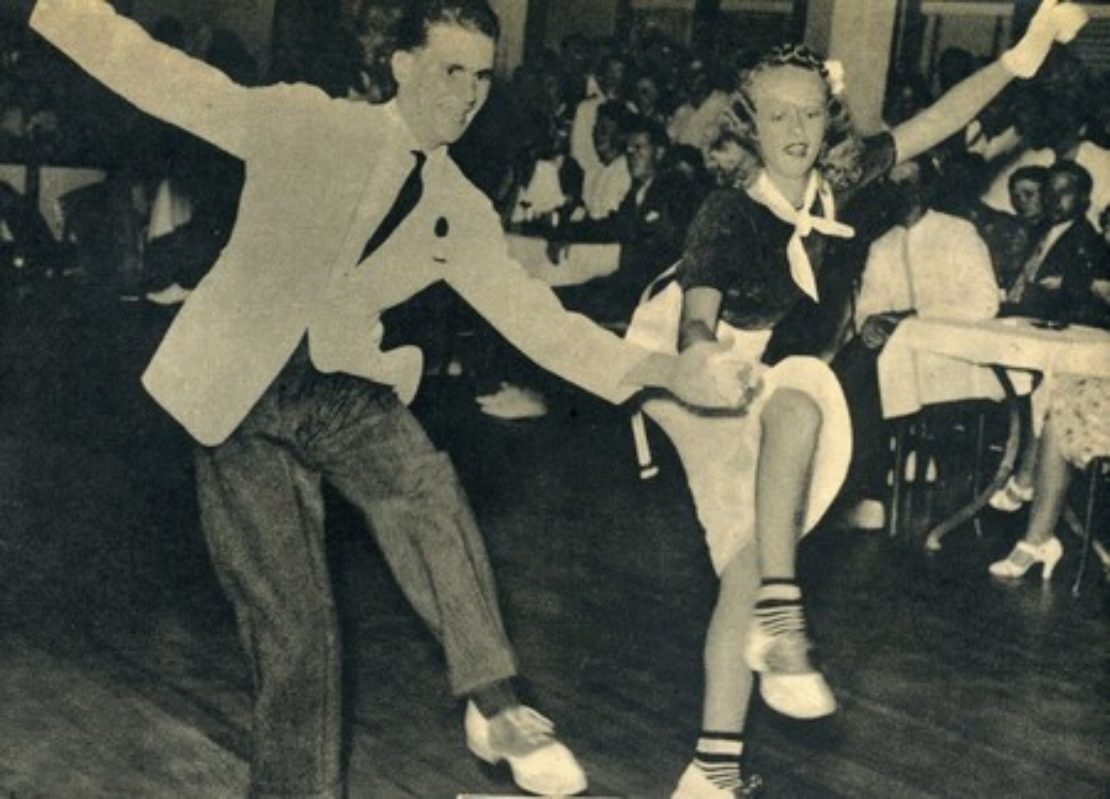

Under the leadership of bandleader Benny Goodman, swing would define pre-war and wartime American music; while its borderless, raceless ubiquity and its popularisation of standards also mark it as the first genuine pop music. It was inevitable, therefore, that 'serious' musicians and jazz fans would find this popularity toxic, birthing in that eternal yin and yang tension of music fandom not only the world's first pop music – but the world's first hipsters.

Most read this month

Fiction: Divided we stand, by Tim Maughan How Scotland is tackling the democratic deficit The Long + Short has ceased publishingThe antipathy towards swing wasn't just rooted in a disdain for the mainstream. Swing, as a continuation of big band's methodologies, persisted in sidelining the polyphonic improvisation of New Orleans jazz in favour of orchestrated arrangements and, increasingly, Tin Pan Alley pop song structures. In his autobiography Father of The Blues, WC Handy used swing as a codename for what he perceived to be the hijacking, commercialisation and ultimate dilution of African-American music by white entertainers:

This brings to mind the fact that prominent white orchestra leaders, concert singers and others are making commercial use of Negro music in its various phases. That's why they introduced 'swing', which is not a musical form.

However, as investigators of genre prototypes, we're not concerned with that golden age of swing Benny Goodman stuff – no Glenn Miller here! And when we examine swing's "period of innovation" – defined by us as the first hour's worth of key recordings germane to a given genre – we see that more than 70 per cent of its musicians were black, the strongest showing for black composers in the series so far, with the exception of the almost-entirely African-American boogie-woogie. The Casa Loma Orchestra and the dancer and light entertainer Fred Astaire were the only white early adopters of swing.

Swing's borderless, raceless ubiquity and its popularisation of standards mark it as the first genuine pop music

We've compiled swing's period of innovation in a Spotify playlist here.

Swing largely took Fletcher Henderson's strain of big band jazz as its starting point and so its genesis at least was certainly more African-American in demographic than anything else. Louis Armstrong had played in Henderson’s band, and Duke Ellington had started out in a similar big band ensemble, The Washingtonians. Along with Cab Calloway and Luis Russell, these men formed the cornerstones of early swing.

Unlike the musics more closely derived from ragtime and blues, which were often rural in origin and spread via travelling vaudeville shows, swing was an urban music, tightly focused geographically around industry recording hubs. Although Armstrong and Ellington were both the grandchildren of slaves (from New Orleans and Washington DC respectively), Calloway was from an affluent Rochester family, and Luis Russell was a Panamanian of Afro-Caribbean descent (the first non-American in this series), which perhaps demonstrates a growing diversity – or, at least, an eroding parochialism – in jazz now that radio and the recording industry were capable of transmitting music to an intercontinental audience.

Another factor that set these new musicians against their jazz progenitors was a more conventional, schooled musical training.

Fluent in violin, guitar trombone and piano, Russell had been raised in a family of music teachers, and was making a living as a professional musician by the age of 15. Similarly, both of Ellington's parents were pianists – from opera and parlour backgrounds respectively – while Calloway's family had recognised their son's talents early on, and invested in private musical tuition for him. Only Armstrong had an edgier musical training. His cornet chops were mostly honed during his time in New Orleans Home for Colored Waifs: a boys' home he had been sent to multiple times for juvenile delinquency, but which boasted a band directed by one of New Orleans' finest trumpet players, Peter Davis.

Our weekly newsletter features a roundup of the best stories of innovation from across the web:

NewsletterBy contrast, the received wisdom on New Orleans jazz suggests that the techniques particular to jazz were the direct result of a community crafting a new musical language, using instruments with which they were largely unfamiliar.

Apocrypha or not, jazz was thought to begin in New Orleans at the end of the Spanish-American war in 1898, when the port was flooded with decommissioned military units and their bands. The Red Hot Jazz website claims that the bands' instruments were quickly and cheaply procured by African-Americans interested in music but lacking a working knowledge of conventional techniques. This led to "new and interesting sounds entering musicians' vocabulary: trumpet and trombone growling sounds, wah-wah sounds, the use of odd household objects as mutes, and others."

The importation of African rhythmic ideas, 'blue notes', non-European scales and endless improvisation allowed a new musical form to germinate. The musicians were thought predominantly to play by ear.

This version of history is fiercely contested by some, however, as at best an over-simplification and at worst, outright racism. Krin Gabbard, Professor of Comparative Literature, SUNY Stony Brook, and the Center for Jazz Studies at Columbia University, says this of the 1955 biopic, The Benny Goodman Story:

White America's conflicted response to the rise of swing and its connection to black culture is clearly articulated in The Benny Goodman Story (1955), a Hollywood film aimed at whites with fond memories of the swing era. This film presents a set of common myths about jazz. In an early scene, the teenaged Benny is playing with a mediocre white dance band on a riverboat. Wandering to another part of the boat, he hears a band of black New Orleans musicians under the direction of the Creole trombonist Kid Ory (played in the film by the real Kid Ory). Benny has never heard such compelling music, and when he quizzes Ory, the trombonist says, "We just play what we feel," a statement that perpetuates the myth that the pioneers of jazz were not trained musicians but primitive people who naively expressed their feelings through music. Endowed with the licence to play from his feelings, young Benny immediately becomes an accomplished jazz improviser as he plays along with Ory's group. Later in the film, after Benny has become a successful bandleader, Ory reappears to tell him that he has "the best band I ever heard anyplace!" Like many other films about white jazz musicians, The Benny Goodman Story found a way to diminish the real achievements of black jazz artists, who were most definitely not playing a music that was an unmediated expression of their feelings. The film also suggests that white artists like Goodman created a music that surpassed anything created by their African American predecessors.

Swing was certainly less anarchic than jazz – it was feelgood orchestral music, purpose-built for dancing. Although sections of a composition would be reserved to allow one instrument the opportunity to improvise a short solo, it was otherwise rigidly composed and musically complex. The lilting off-beat emphasis of the music is the titular 'swing', although the genre would not be known by that name until the arrival of Duke Ellington's It Don’t Mean a Thing If Ain't Got That Swing in 1932.

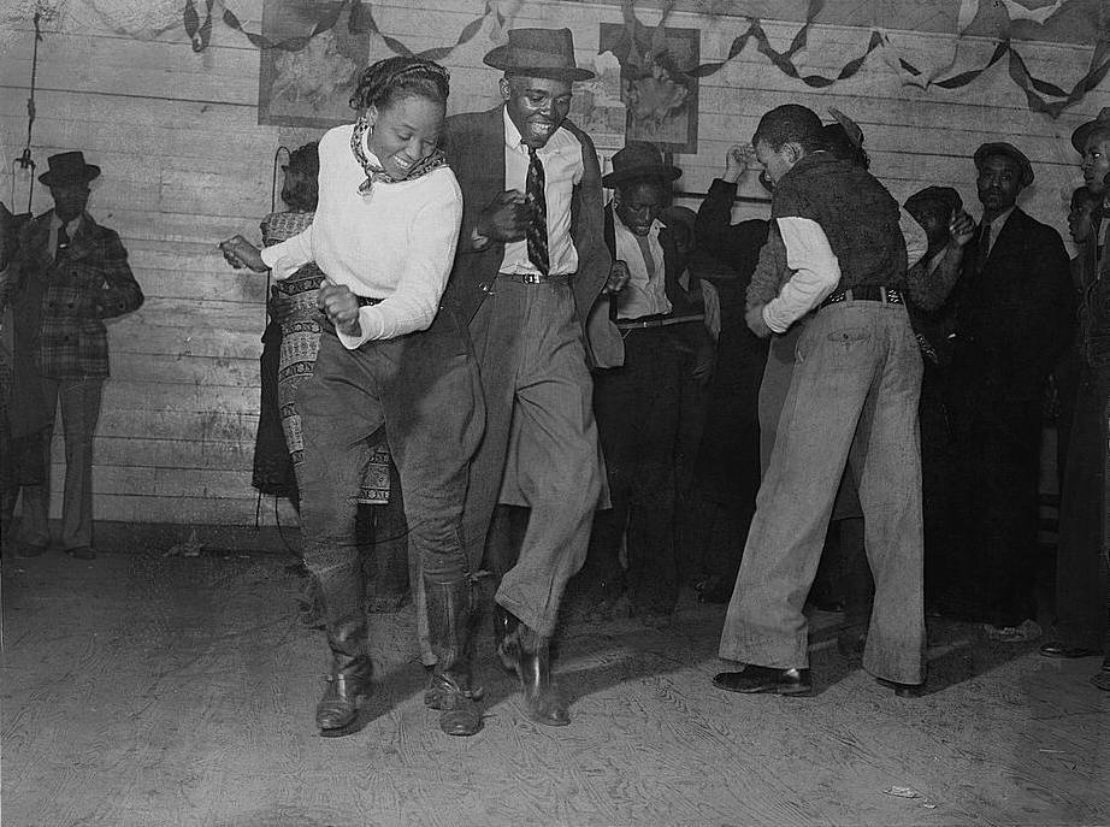

Dancers were inspired by swing more than any dance music in the 20th century: the Lindy Hop, Balboa, Collegiate Shag, Charleston, jive, Big Apple and Little Apple are just some of the dances that come under the umbrella of 'jitterbug' dance

But was swing really the antithesis of jazz? In Escaping The Delta, Elijah Wald flags the jazz versus swing debate when tracking the subdivision of blues into an array of child categories:

In jazz, there came a moment when a group of fans tried to declare the whole category closed. The New Orleans music originally called jazz was jazz, they said, and 'swing' was something else. Less hard-line members of the clan might even admit a Duke Ellington or a Benny Goodman to the jazz pantheon, but still barred boppers like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. The New Orleans purists were dubbed 'mouldy figs' and eventually lost the battle, and with their loss it was generally agreed that the word 'jazz' – like the word 'classical' – would apply to a huge range of musics, some of them so dissimilar that if one did not know the historical links one could hear no connection between them.

Wald's point is not that jazz was diluted by the admission of swing into the jazz dynasty. Rather, he is emphasising Louis Armstrong's point, quoted at the start of this article. "It cannot be said enough," argues Wald, "that musical categories are artificial constructs: useful for many purposes but meaningless and limiting for others."

"Every category is defined with a set agenda in mind," Wald continues. "Sometimes a historian wants to make a point. Sometimes a marketing executive wants to make it easy for consumers to find a particular kind of product. Sometimes a performer wants to distinguish himself or herself from previous artists, or those with whom he or she disagrees about something. There is nothing wrong with any of this, but there are always confusing examples that illustrate the limits of the taxonomy."

In this series, we are interested in taxonomies as markers staking out notable points of innovation in music that was made for dancing. They're admittedly imprecise; Louis Armstrong was a working musician from the inception of jazz itself through at least a dozen relatively major shifts in the sound that prompted new evaluations and terminology, but all he heard in any of it was the ragtime of his youth.

Nevertheless, swing did introduce new elements to the jazz vocabulary – the 'call and response' between band sections, pioneered by Fletcher Henderson in the big band era and honed into a catchy, intricate pop music by swing, was a hit with audiences. And dancers were inspired by swing more than any dance music in the 20th century: the Lindy Hop, Balboa, Collegiate Shag, Charleston, jive, Big Apple and Little Apple are just some of the dances that come under the swing dance umbrella term of 'Jitterbug'.

Could it have been this unashamed commitment to keeping feet moving that caused fans of jazz – soon to become a music estranged from its dance music origins, a 'head' music – to consider swing so frivolous? White folks, yo' all sho is a mess.