Replicas of an unstable world

Two very different types of artistic copy frame the entrance to A World of Fragile Parts, the Victoria and Albert Museum's exhibition at this year's Architecture Biennale in Venice.

A 19th-century plaster copy of an arch from the Basilica of San Petronio in Bologna, taken from one of the V&A's grand cast courts, hangs above the entrance. It is canonical: classical, authoritative, privileged. A few paces on, a white, igloo-like structure stands sturdy. This is Dar Abu Said – the House of Abu Said – a 1:1 replica of a shelter at the 'Jungle' refugee camp in Calais.

Abu Said is a Sudanese refugee, whose temporary home is made of plastic and wood. The replica created by the London-based architecture and design practice, Sam Jacob Studio, has been made from a 3D scanning of the original, which has then been rendered in CNC (computer numerical control) milled synthetic stone.

Both pieces are products of their time. There is juxtaposition in their creation and in their subject matter. One is a painstaking plaster copy that depicts God and the prophets. One uses digital tools of preservation and reproduction to respond to an ongoing crisis. At the opening of the exhibition, research curator Danielle Thom tells me that Dar Abu Said "takes something very ephemeral – both in its material terms and in the way it's regarded socially – and by turning it into stone, the act of copying changes its status. Suddenly it has artistic status as a monumental sculpture."

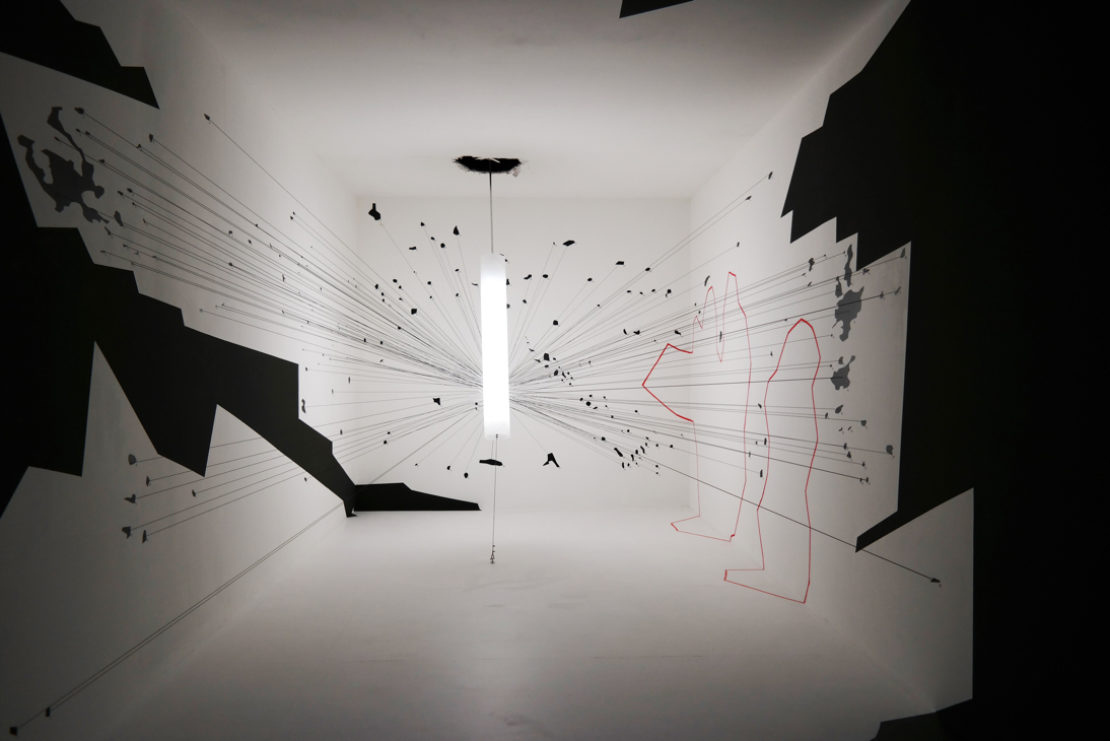

This status is also present in the work of Forensic Architecture, a project headed up by Eyal Weizman, an architect at Goldsmiths University. Weizman's group displayed beautiful 3D renderings of the clouds created by bombs, including one from Rafah, Palestine, which was the result of two one-ton bombs being dropped on a residential neighbourhood by the Israeli air force. Forensic Architecture's renderings are used in human rights work and to solve legal cases – they are able to establish, using architectural modelling tools and images collected from social media, who did the bombing and who was the victim. A bomb cloud is made of everything a building once was, and so it is architecture in gaseous form.

Weizman believes all monuments are political statements and that a bombing itself is a political statement, so when you render it solid, that idea is reinforced and the violence of the situation becomes more visible.

Curator Brendan Cormier tells me that the exhibition was inspired by the "incredible, visceral experience" of being in the cast courts at the V&A, and the destruction of cultural artefacts in the Middle East last year. These artefacts, like the arch at Palmyra, which was destroyed by ISIS in October 2015, can be brought back using fabrication, photo imaging and photogrammetry. This technology has made the process of copying quick and relatively easy to do. "The Palmyra arch that we have on display here, they were making the modelling, milling it with a robotic arm in Italy, all while the conflict was happening," says Cormier.

Sign up to our newsletter

Photogrammetry – whereby hundreds of 2D images are stitched together into a 3D file – can be carried out by anyone with a digital camera and access to the internet. "Anybody can walk into a museum, take 40 pictures of an object and then upload a 3D file onto a platform and share it with the rest of the world," says Cormier. "It occurred to me that there was a strong need to update the V&A's 19th-century tradition of making copies for the 21st century, with all this new technology around."

The exhibition, then, can serve as the beginnings of an update on the conventions for the reproduction of art, first formulated in European kingdoms of the 19th century.

The process of copying has changed and what is copied has changed. What you choose to copy reflects what you ascribe value to. "In the V&A's cast court, what you see is the objects of the victors – like Trajan's column", says Sam Jacob. "Perhaps this kind of technology allows us to tell other stories."

Eddie Blake, a senior designer at Sam Jacob Studio, who visited Calais in order to create Dar Abu Said, says that the piece is bringing the 'frontline' to the Biennale, pausing the political moment by capturing it with 3D technology and raising awareness of the refugee crisis. In this sense, the piece acts – as much of the Biennale acts – as the architectural equivalent of a comment or opinion piece in a newspaper. It sketches out a subject, offers a position and raises questions.

The theme of the Biennale as a whole – "reporting from the front" – is geared towards this kind of provocation. This raises a number of issues. How, amid the drinks receptions and sparkle of beautiful Venice, can the often brutal, unchanging realities of the frontline be addressed?

I asked Eddie Blake about how the migrant crisis can be tackled in this context. "It jars," he says. "It is a question of care. So much care and attention is put into the Biennale, so little is spent on the inhabitants of the Jungle… But perhaps bearing witness is the best we can do. Auden said something like, "Poetry makes nothing happen", but I think ideas do. And perhaps the role of the Biennale is to share ideas."