Whitehall's revenge: Will the Government Digital Service be broken up?

Let's assume that those reading the runes are correct and that the growing belief that the UK's Government Digital Service, the hipster cuckoo in the civil service nest, will soon be no more – or at least be divvied up and and flung back across the departmental estates of Whitehall.

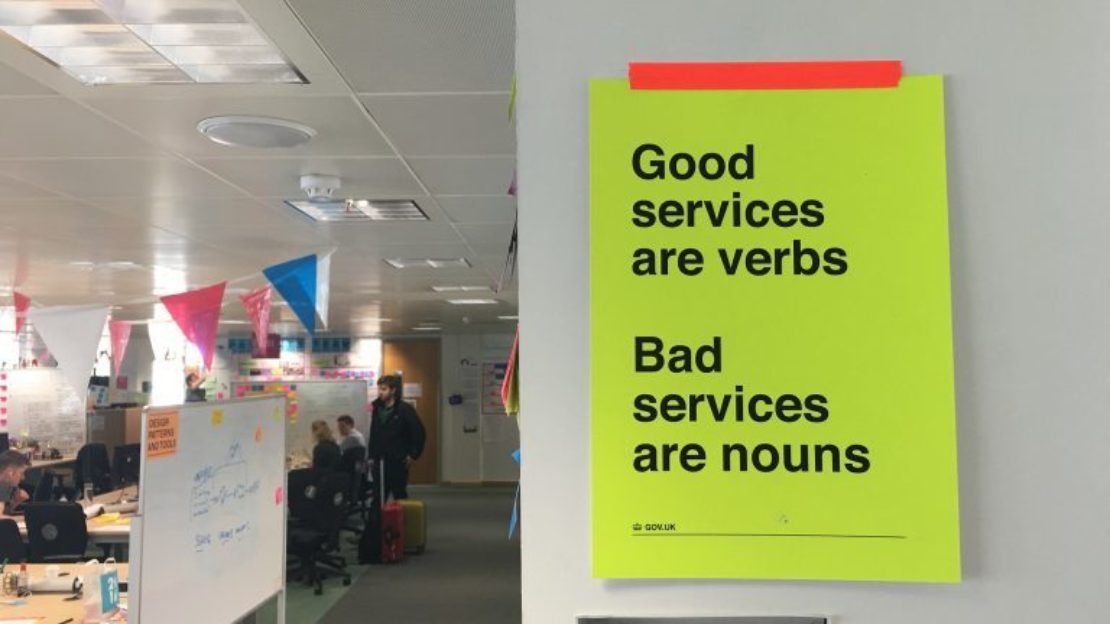

The GDS was set up in 2011 as a unit of the Cabinet Office, charged with transforming and centralising how government runs services online. It has drawn plaudits around the world, and its key effort, the GOV.UK web portal, won the Design Museum's Design of the Year in 2013. Now, however, a brief, golden period of digital innovation and cultural change is threatening to come to an end.

If the fears bear truth, the age of centralised digital services, of Government as a Platform, is passing even before it came to fruition. The opportunity to bring top-level digital skills into government, to develop digital solutions to delivering services, for an overarching policy on the use of data and a shared approach to technology is now threatened. It would be a crying shame – but perhaps, sadly, quite inevitable.

As we move away from the short dawn of 'user-first' government service design and back to the old habits of 'departmental needs', with senior civil servants anxious to claw back control over departmental digital services (and budgets), the old order is being restored. There's already a growing list of departing digerati; swathes of top GDS management have left over the last year, and digital leads at various government departments are said to be leaving too. Both the leaders and their collaborators are disappearing.

A brief, golden period of digital innovation and cultural change is threatening to come to an end

GDS has worked to streamline all government services and bring disparate single-service websites together, but now departments are creating competing services. The Department for Work and Pensions and the HMRC were excluded from GDS's last budget negotiations, and are free to move in their own direction – which is thought to include creating their own identity assurance programmes, despite the launch of GDS's Verify.

To be clear, the new head of GDS, Kevin Cunnington, has denied any plans to break the GDS: "I want to strengthen and accelerate the pace of change… the GDS will not be broken up," he wrote last week. Granted, few would enter such a job and say "I'm here to smash the place up", but the fin de siecle mood is unmistakable.

Across Whitehall, there is a sense of comeuppance about this. Of revenge served by those whose hackles were raised by the very chutzpah that drove GDS's brief success.

The default outlook of the new digital leadership always felt tone deaf to the establishment context in which it worked – but that wasn't deliberate. The new influx of techies instinctively adopted the self-confidence of the TechCity/Shoreditch culture where many felt at home. And in EC1, that sense of self-worth felt very natural in the artisan coffee shops. A few miles to the west in the Costas and Neros of SW1, it would have felt jarring and confrontational.

Internally, that chippiness created a sort of 'us vs them' mentality which would have been useful – it drove the reforming zeal and allowed them to attract real digital talent ("you're not joining the civil service, you're joining GDS"). The hubris, however unwittingly cultivated, continued to build.

Sign up to our newsletter

A while ago I had a call from someone at the GDS who wanted to interview me about my part in its birth. He was, it turned out, writing its 'autobiography'. A four-year-old subsidiary of the Cabinet Office wanted to document its own story (I had a negligible bit part at the very start). To civil servants, that reeked of over-confidence about your place in history. And yet, internally, it would, again, have felt normal. They were in a culture which viewed them as 'weird hippies', so making sure that they owned their own narrative was simply classic, front-foot, communications strategy, taken up in a civil service world that is largely reactive.

It's fine to have a sense of confidence, and natural to various parts of the civil service. The problem with the GDS was that that confidence too often tipped into separateness – the key figures of GDS always saw themselves as loaned to the government, not as career civil servants. That gave them a different perspective and they were able to build outside of the endless legacy of Whitehall, to rip it up and start again.

But it sounded smug and it ruffled feathers, especially among the IT community long fed on lengthy contracts with heavy-duty suppliers. To add to that atmosphere with increasingly aggressive criticism of senior civil servants and politicians was asking for trouble and felt like an excuse for slow delivery and an attack on their hosts. It wasn't forgotten.

GDS has a different perspective and is able to build outside of the legacy of Whitehall, to rip it up and start again. But it sounded smug and it ruffled feathers

When Francis Maude left government, the GDS lost its ministerial cover. From Maude to Matthew Hancock to Ben Gummer as the ministers responsible for digital delivery is a clear set of downward steps. As it became safer to do so without feeling at odds with the zeitgeist of SW1, so the failings of the new era were seized upon with increasing glee.

Expect more of that – more 'leaks' regarding things that haven't been delivered well enough, on time or on budget. And more of a sense that things aren't all they're cracked up to be – the backlash has started and won't stop till everything is 'back in its place'. Digital delivery may remain significantly better than it was six years ago, but the central drivers will be gone, the pace of change will slow, the big IT suppliers, the Accentures and the CapGeminis, will play an increasing role, perhaps even forcing out the new wave of smaller-scale, more agile suppliers that GDS did much to encourage. All will be (almost) as it was, with just the sense that things could have been so much better.

GDS will be the civil service's punk era. Brief, exhilarating and driven by a different kind of individual – with a different dress sense and a different sense of purpose. But, as with punk, it fizzled and faded and, before we knew where we were, we were listening to the old sounds once again. The sound of old Whitehall reasserting itself.