Sharing plates

There is an egg glut in my fridge, the result of over-enthusiastic ordering from the farm delivery service, marital miscommunication (best not gone into here) and general domestic incompetence. Some of these eggs are approaching their best-before date.

I do not want my perfectly edible eggs adding to the 7m tonnes of food waste thrown away by UK households every year. On the other hand, my family's patience with egg-based dishes is running out.

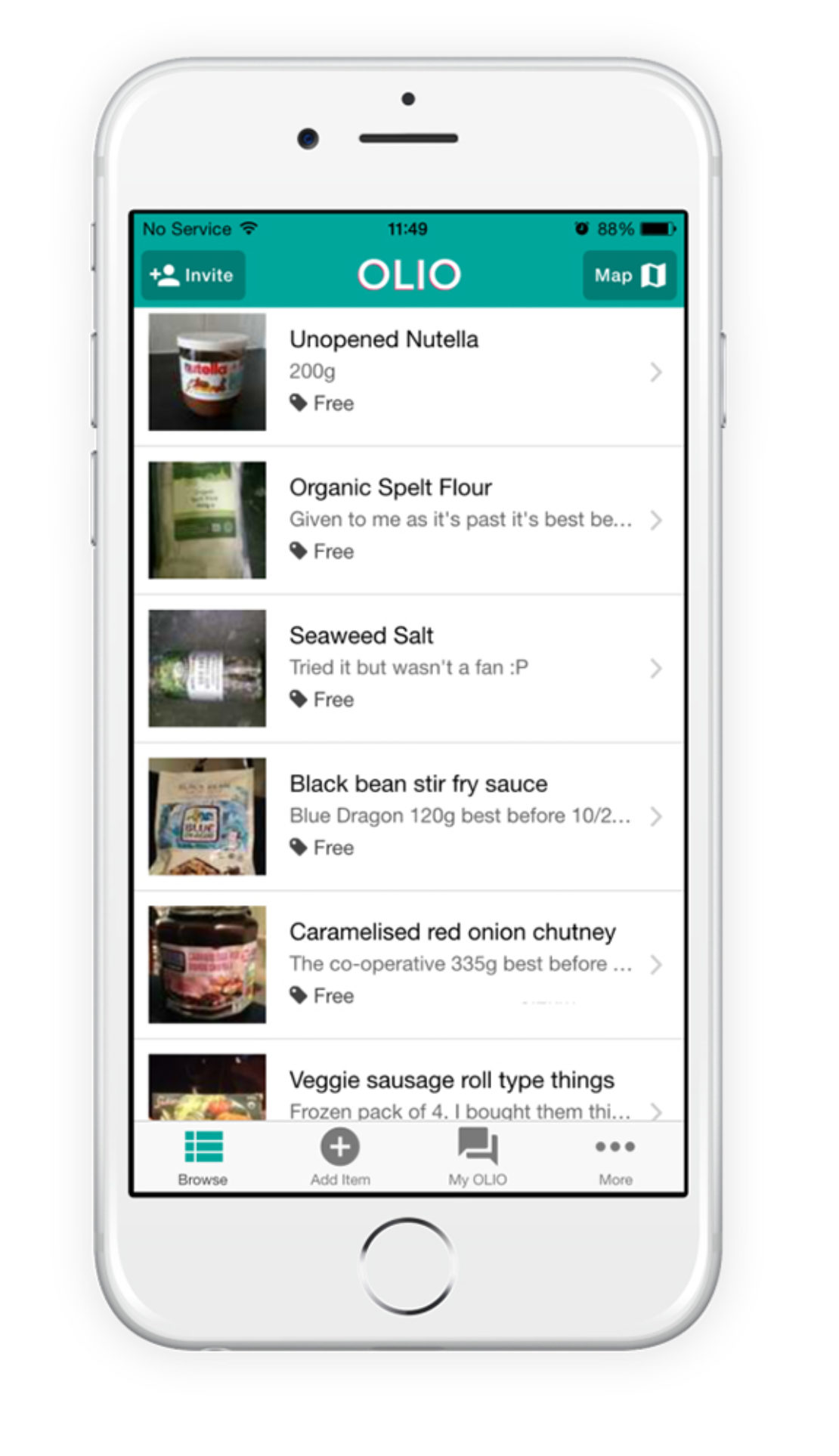

Happily, there is a solution. I take a photo of my eggs and post them on Olio, an app that allows people and shops to share surplus food (the name, according to its founders, is a synonym for hodge-podge). Within five minutes, two people who live nearby have messaged offering to come and take the eggs off my hands.

After a bit of back-and-forth, I agree a handover time with the first of these. Katherine duly turns up. She is pleased to have some free free-range eggs. And I am pleased to have done my bit.

I don't want my perfectly edible eggs adding to the 7m tonnes of food waste thrown away by UK households every year

Food waste is a planet-sized scandal. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation, we waste one-third of all food grown globally, about 1.3bn tonnes. This accounts for 28 per cent of the earth's agricultural area (roughly the size of Mexico), for 3.3bn tonnes of CO2 emissions and a staggering amount of water. Tristram Stuart of the campaigning organisation Feedback says that the world's 1 billion malnourished people could eat perfectly well on the food wasted in the US alone.

Set against these statistics, my eggs start to look rather paltry. I wonder whether rescuing micro-quantities of food at a hyper-local level can really have any impact.

Sign up to our newsletter

Hoping to be persuaded, I go to meet Olio's co-founder at the business's makeshift HQ in the downstairs half of a small terraced house in North London. Saasha Celestial-One (it's her real name: her parents were hippies in rural Iowa; it is, she says, "what they put on my birth certificate") is a 40-year-old American former banker and consultant.

After a childhood of hardcrabble chaos, Celestial-One says she "sought stability in my CV," studying economics at the University of Chicago (including a year at LSE) before working at Morgan Stanley and McKinsey. She met her Olio co-founder, Yorkshire-born Tessa Cook, when they were both studying on the MBA program at Stanford.

They became close friends when Saasha moved to the UK in 2005. Having had children at around the same time, they wanted slightly different things from their careers, mainly less travelling. (Saasha has a four-year-old and Tessa a three-year-old, a two-year-old and four older stepchildren.) The inspiration for Olio came from Tessa's distress when she was leaving a posting in Geneva and found that she was unable to offload her leftover food, even though she knew there were people nearby who could have done with it.

"We put in £20,000 each and decided to give ourselves a year," Saasha says, "if it didn’t work, we’d have to go back to real jobs."

Initial research with a few hundred people in Crouch End, where Saasha lives, and with YouGov, found that one-third of respondents said they felt physically ill when they threw away food that was recently edible. Around 90 per cent were prepared to walk 10 minutes to pick up free food.

Olio launched in July 2015, following several months of leafleting and community PR. That August, the founders raised seed funding from Excel Venture Management, enabling them to hire staff – including the two of them, they employ eight people, all working remotely.

The app has had more than 100,000 downloads. Initially, Olio focused its efforts on London; since January, it has rolled out in Bristol, Brighton, Edinburgh, Oxford, Cambridge, Leeds, York, Cardiff and Newcastle. "We have gone for the places where independent organic shops thrive, because that’s where you find the early adopters," Saasha says. But it has also had striking success in Swadlincote, Derbyshire, where Sainsbury's is spending £1m on its Waste Less Save More Campaign, supporting various initiatives to reduce food waste with a view to rolling out the most successful nationwide. More than 1,000 users have signed up in the town, sharing 2,000 items in six months.

An estimated 20-40 per cent of fruit and veg never reaches the shops, rejected on aesthetic grounds or because of cancellations

"It's not an Airbnb destination, there’s no sharing economy profile there," Saasha says, "and we weren't really convinced it would fly. But there's a bargain-hunting mentality. And when everyone's doing it, there's no stigma."

The idea of eating for nothing is undeniably tantalising. Olio will be featuring in a BBC documentary about food waste scheduled for November; and in an episode of Jamie and Jimmy's Friday Night Feast with Jamie Oliver and Jimmy Doherty in early 2017; and on ITV's Cook Yourself Rich.

Most read

Why the world wide web will break up Is there such thing as a 'criminal' face? Are women the answer to our uncertain political times?There does, however, remain a significant hurdle. Olio will have to achieve local density at the same time as scale – because the exchange only really works when sharing items are within walking distance: only then is the threshold for sharing sufficiently low to be really effective in dealing with waste. To be honest, my free range eggs were probably always going to be picked up; I am not quite ready to inflict the two carrots I accidentally cut the tops off to people who would have to travel a couple of miles to get them.

There is also a more theoretical question, which may or may not make a difference to perceptions of the app: by giving away a couple of carrots, are you really making a difference?

Food is wasted in shocking quantities at every stage of its growth and distribution. An estimated 20-40 per cent of fruit and veg never reaches the shops, rejected on aesthetic grounds or owing to last-minute cancellations of orders. Supermarkets deliberately overstock, since consumers are psychologically attuned to respond to amplitude by buying in greater quantities. Once food approaches its best-before date, it often goes into landfill. In France, it became illegal earlier this year for supermarkets to throw away edible food or spoil it, usually with bleach, to prevent foraging from dumpsters; it must now be donated to charities feeding people who are hungry. This is not the case in the UK.

By giving away a couple of carrots, are you really making a difference?

Activists may argue that consumers would do better to focus on the rottenness of the system rather than worrying about the couple of almost-off carrots in the vegetable drawer. Saasha Celestial-One's response is that households are responsible for around half of Britain's food waste (a figure supported by the government-backed WRAP). And food waste is such an enormous problem that it needs addressing on many fronts.

There are of course innovations targeting different stages of the supply chain. The Real Junk Food Project supplies 14 cafes and a warehouse-supermarket (both 'pay-as-you-feel') in Leeds using supermarket waste. The model has been copied across the UK and abroad. Rubies In The Rubble uses supermarket waste in its upmarket chutneys and relishes. LeanPath provides technology to enable restaurants and catering establishments to measure what they are wasting so they can adjust their menus and ordering accordingly (Google is a client).

I have wondered several times over the last few days about Katherine and what she did with my eggs. Not least in these post-Brexit times, when Theresa May worries about us being "citizens of nowhere", it feels good to be able to do something in the community, something that generates a feeling of mutuality and social solidarity. Food waste activists are probably right that the food system needs a revolution; but in the face of the helplessness engendered by being a mere end user, I like the idea that there is something that I, and my eggs, can do.