Cold cases

In a modest room no larger than 20 sq m, many thousands of animals, from the Cuban crocodile to the Hawaiian honeycreeper, lay carefully preserved in liquid nitrogen. "There is no place on Earth where there is so much living material from so many species," says Dr Oliver Ryder, pointing to some storage tanks. "It's the most biodiverse place on the planet."

The 'Frozen Zoo' at San Diego Zoo in southern California houses sperm, eggs and genetic material from more than 10,000 dead animals in total, safeguarded for posterity to preserve genetic diversity, and in the hope that scientists might be able to help save endangered species, or even one day reintroduce species that have long been extinct.

Dr Kurt Benirschke, a pathologist and geneticist, founded the Center for the Reproduction of Endangered Species at the San Diego Zoo in the early 1970s. It was the first research department of its kind, established to study the chromosomes of mammals and particularly those aspects relating to reproduction and evolution.

Dr Ryder, then a young molecular biologist, joined Dr Benirschke at the zoo in 1975, and the pair's focus turned to applying molecular genetics to endangered species.

"At the time, you didn't hear anybody within the academic world talk about conservation," Dr Ryder remembers. "There was a lot that could be done and it was just going be a challenge to figure it out."

Benirschke and Ryder collected the cells and reproductive material of highly endangered species for cryopreservation, with little idea of quite how they could be used in the future. Today that collection, amassed over 40 years, has come to constitute perhaps the richest genetic resource on Earth, comprising cell samples from some 1,000 species and subspecies of mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians. It will soon add its first insect.

When we arrive at the facility, Dr Marisa Korody, senior research associate in genetics, is chopping up the ears of a recently deceased Pacific pocket mouse into 1mm chunks. The animal was a 'founder': caught in the wild, and thus possessing more valuable genes, ones not diluted by captivity.

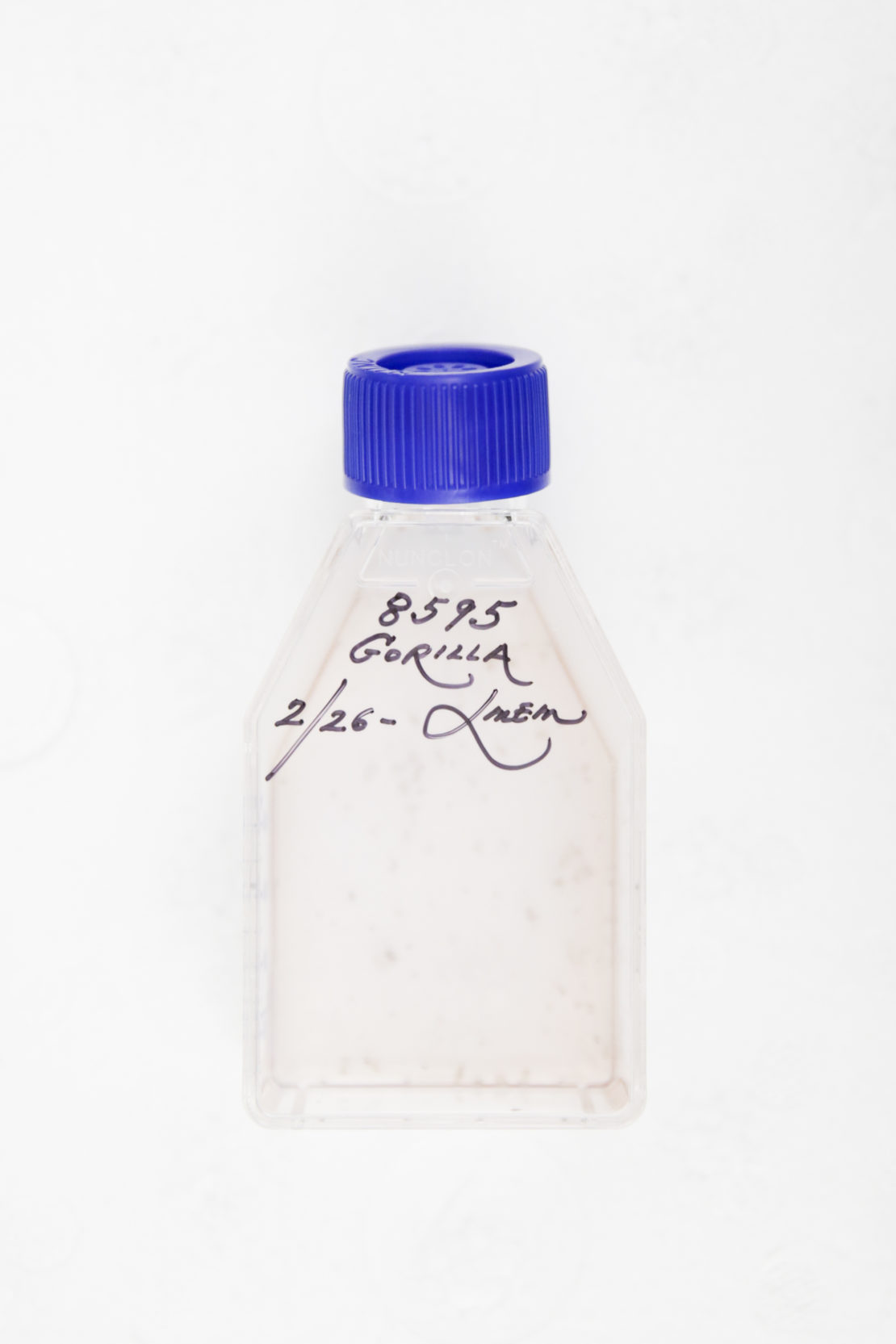

In the cell culture lab, Dr Korody incubates the chunks of mouse matter for six hours, mixing them with an enzyme that digests the tissues and liberates the cells. The cells will next be kept here to grow – a process that takes anywhere from three weeks to more than a year, depending on the individual specimen. While we are in the lab, the cells of gorillas and southern white rhinos sit developing on the shelves.

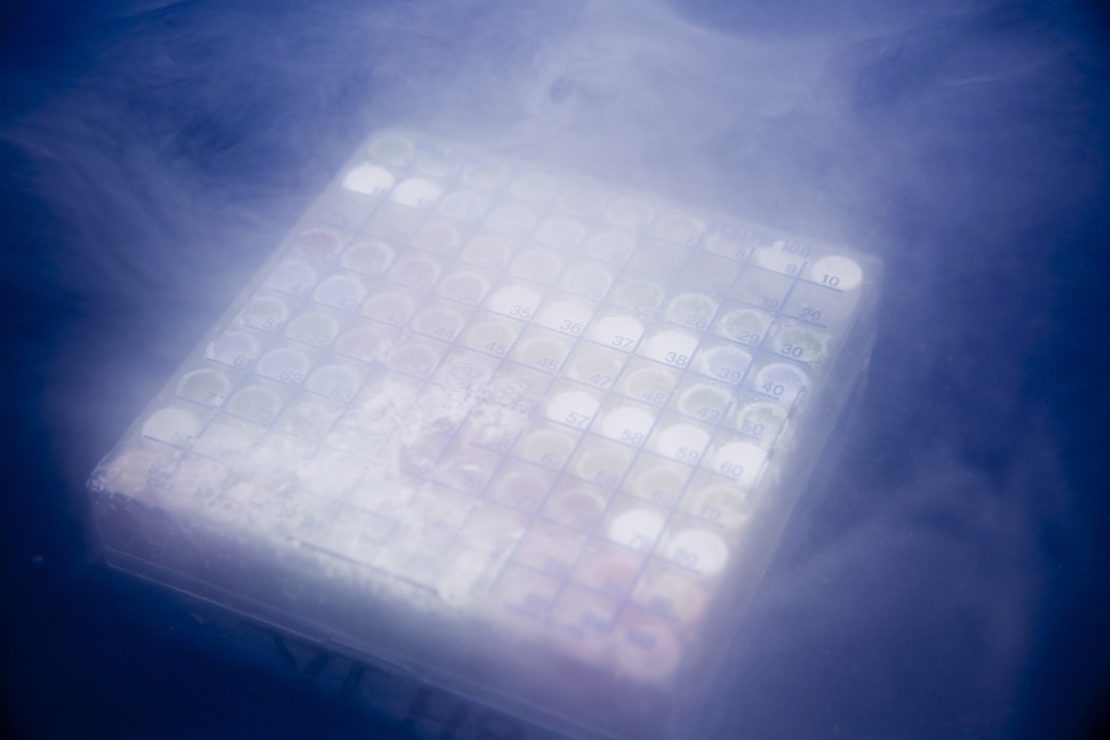

Back in the main room, Nicole Ravida, senior research coordinator in reproductive physiology, is slowly freezing the mouse's testicles. The loud ticking of a timer almost drowns out the voice of Marlys L Houck, senior researcher in genetics, who guides us around the facility. As Houck opens the metal tank containing the frozen cells, it releases the roaring sound of a pressure cooker. She pulls out a samples rack in a cloud of nitrogen, and carefully extracts a 100-vial box. Inside the tiny flasks, beneath colourful corks, are the cells of a Micronesian kingfisher, a Cuban crocodile, an African elephant, a koala and a dik-dik, the smallest antelope on Earth. There are also the cells of an extinct species of bird, the Hawaiian honeycreeper.

The frozen zoo – San Diego's is not the only one – arose from the demise of zoological parks. Once the most lucrative public attraction, zoos lost their appeal as a reluctant visiting public started to develop ethical issues about animal captivity as entertainment. Zoos were thus required to become pioneers in zoological research to remain legitimate and sustainable.

Dr Ryder's first revelation happened in the 1980s, when the American Society of Human Genetics hosted the presentation of a PhD researcher who demonstrated that one could take a hair and genotype it (determine its genetic makeup). Though the presenter was foreseeing the forensic applications of her discovery, Dr Ryder used it to perform the first studies on wild mountain gorillas, which was a controversial subject at the time.

Inside tiny flasks were cells of a Micronesian kingfisher, a Cuban crocodile, an African elephant, a koala and a dik-dik, the smallest antelope on Earth

Then in 1996, the world's 'holy cow!' moment arrived: Dolly the sheep was born in Edinburgh – the first mammal born from somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), popularly known as cloning.

"You talk about changing your opinion – you really have to do this in science – and I was trained to accept the dogma that once the cells are differentiated, they could not be de-differentiated," says Dr Ryder. "I didn't even want to discuss ideas about using cells in the frozen zoo to recreate animals because I thought it was a sensationalist diversion."

Yet Dolly proved that it was possible to take a single cell and ultimately produce a functional animal capable of reproducing itself.

The zoo later made auspicious discoveries around the ability to reprogramme a cell: to take it from its developed stage – a skin cell or a nerve cell – and make it become pluripotent (able to make any cell in the body).

"That was outstanding when you think that we have possibly the world's most diverse collection of stem cells," says Dr Ryder.

This inevitably leads to delicate questions about their use. Dr Ryder's position is to avoid molecular cell transfer unless it is absolutely necessary. Cloning, he says, comes with a series of consequences that haven't been studied enough yet. (The San Diego zoo performed cloning once, in 2003. The successful experiment resulted in the birth of a banteng – a species of wild cattle found in South-east Asia.)

Reintroduction to the wild is another major challenge for the zoo, especially for species of amphibians that are kept in captivity in environments very different from their natural habitat.

"Historically, it was underestimated how big a problem reintroduction was," says Dr Ryder. "But it is amenable to some research. The problem is that we are in a race against time. Some of these species are not surviving in the wild and our only choice for saving them sometimes involves these very intensive technologies."

If we save cells, we will have a lot more options. If we can keep them for a long time, we will change the potential of biodiversity of the planet

This is striking when we look at efforts directed towards the protection of northern white rhinos, the zoo's principal cause. In Kenya, at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy, adequate protection requires heavily armed anti-poaching militias watching over the animals 24/7. For less critical subspecies, preventive measures consist of immobilising animals and cutting off their horns in order to discourage ivory hunters.

At San Diego, it's another kind of immobilisation. The three remaining northern white rhinos are too old to reproduce naturally and the only alternative to avoid their extinction is to make use of assisted reproductive techniques, with a female southern white rhino as surrogate. Using cells from their collection, they have sequenced the genomes of the cells of both subspecies and determined that they are compatible. Still, it's an ambitious undertaking.

"It's unprecedented. We will have to do embryo transfers, which we have never done on rhinos, but every step we have taken on rhinos is not a fantasy, it's an activity that's been done with other mammals," Dr Ryder says.

Methods may differ, yet on each continent conservationists aim to adjust an animal to enable it to survive in today's wild environment, where space is ever more scarce and hostile. So, what do we want for the future?

"The choice to bring species back from the brink of extinction one species at a time," says Dr Ryder, "may not be a solution that everyone sees as perfect. But it might be a solution that most people will appreciate is the right thing to do at this time."

"We sit here today and guess about this, and we will probably be wrong. One thing I am pretty sure about, though, is that if we save cells, we will have a lot more opportunities and options. If we can keep them for a long time, we will change the potential of the biodiversity of the planet."