Chasing 'legal highs'

One morning in June 2011, a bag of powder arrived for Simon in the post, unsolicited. The label included nothing but a strange chemical name and the illustration of a molecular structure. The 19-year-old stood for a moment, considering its contents.

Simon had tried a lot of drugs and even dabbled in clandestine chemistry at home – extracting mescaline from a cactus, preparing changa from some mimosa bark. He knew more than a little, but not enough to guess at what he had in his hand.

Whatever this powder was, it was free. "Why not?" He got a pen and wrote the unfamiliar name – methoxetamine – on his arm, big enough for a doctor to find, just in case. He eyeballed a 10mg measure and then, as they say on the drug forums, he "insufflated".

"Even from a small bump I can usually tell, 'No, that’s not what I want'," he says.

This wasn’t Simon’s first time inhaling a mysterious freebie. In place of lab rats and clinical trials, early adopters like him play a vital role in the online drugs market. Suppliers of newfangled substances often send samples to regular clients like Simon – psychonauts, as they are known – who try them out and describe their highs in intensely detailed, lab notation-style reports on drug forums. Simon contributes his findings to Psychonautwiki.org, a Wikipedia-like site for pooling information on new psychoactive drugs.

The day he sampled methoxetamine in 2011, he was on his way with some friends to Stonehenge to celebrate the summer solstice. Satisfied he wasn’t allergic, he took a little more en route.

"I just kept on doing little bumps," he says. "I mean, I did go mental with it in the end. Got to the point where I thought I wasn’t coming back."

Simon’s reasoning is that a drug will never be entirely novel by the time it reaches him: "Someone has to have tried it. At least the chemist."

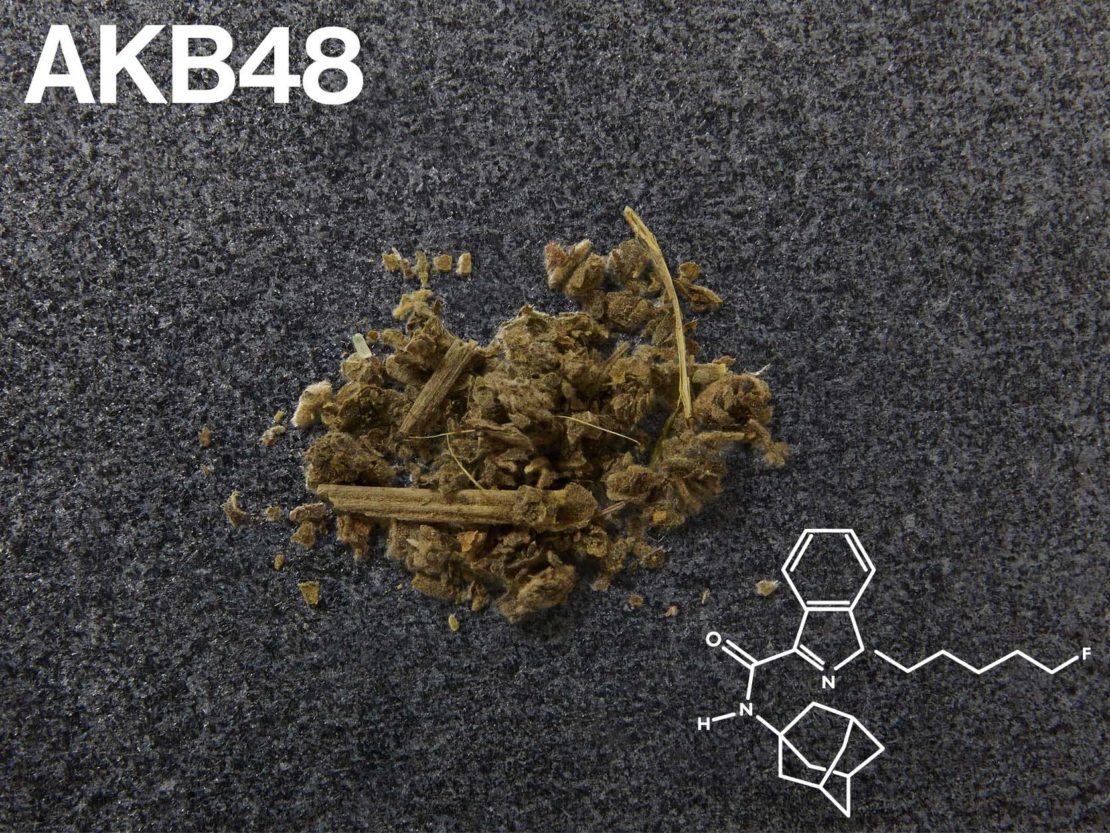

In 2014, dozens of drugs were introduced this way, at a rate of more than one per week. Chemists tweak known narcotics to inhabit a legal grey area, staying one step ahead of regulations. When a substance is banned it is quickly replaced, often by several others. According to one count, more than 350 so-called "legal highs" now exist in the UK. Branded versions are sold in gaudy packaging at head shops, takeaways and petrol stations, frequently in mystery-meat blends. To skirt the Medicines Act, the packets are labelled, "Not for human consumption", and generally feature no ingredients information or dosage guidance.

Formulas for many of these drugs have in fact existed for years, but have languished in obscure academic texts, or among the 100-plus psychedelics pioneered by the grand wizard of drug design Alexander Shulgin. Others are quick molecular hack jobs, changed just enough to be considered novel. Few are such marvels of original design as methoxetamine (MXE), or have enjoyed such a smooth and successful path to market.

MXE was developed by a British amateur pharmacologist and psychonaut known online as fastandbulbous. It is a product of rational drug discovery, in which the scientist works theoretically, on a chemical hypothesis rather than with a series of trial-and-error lab tests. Fastandbulbous’s theory was he could improve on ketamine’s dissociative high (where the user feels detached from reality) in several important ways: as a recent journal account of the emergence of MXE and other similar drugs describes, his formula substituted one compound to increase duration and potency, and another he speculated would provide an opioid analgesic effect, making it "more fluffy", while retaining the overall character of ketamine.

Having arranged for an online contact to synthesise a sample, fastandbulbous injected himself with 25mg. On 13 May he wrote up his first, blissful experience on Bluelight.org, describing the high as "heaven on earth". He tried some more, and fastidiously picked apart its effects, contrasting them with those of related compounds with the flowery enthusiasm of a wine connoisseur: "It does have a lot of the emotional enhancement that, say, 3-MeO-PCP has, but it also has a certain je ne sais quoi that makes it something rather special, in my opinion." Immediately, the forum thread lit up with requests for more information on its chemical structure.

In September, UK legal highs supplier, Buy Research Chemicals, began sending samples to a few regular customers. More glowing "trip reports" followed, and a fuller picture of its effects began to emerge, including the fact that it was highly addictive. In October, an overdose of MXE was reported in Harlow.

By July 2011, a year after fastandbulbous first wrote about his discovery, 58 sites were advertising MXE for sale at affordable prices. It was banned, initially with a temporary order in April 2012, then as a class B drug in March 2013.

Governments everywhere are scrambling to better legislate against these drugs. In the UK there is rising support for the Irish model: a blanket ban on new psychoactives. But it’s still not clear how well this approach works. Following the ban, most Irish head shops have been shuttered and, according to law enforcement, there are fewer hospitalisations from these substances. Nonetheless, rates of abuse of novel drugs, bought from overseas websites, remain among the highest in Europe.

Online suppliers often steep their sales pitch in pseudo-scientific jargon. Some even list lab equipment like beakers and weighing scales in their product line. Holland-based supplier DeboraLabs released a glossy animation advertising their reliable "peptides supplies". The clip, and the whole organisation, could almost pass for a pitch to some imagined cottage industry of independent scientists. A similar vernacular prevails on drug forums: drugs are known by their chemical name, the user’s body is a lab. ("I think I am going to bring this 'bk-2C-B' into my lab and do some testing on it," writes one psychedelics user.)

Self-experimentation was once an intrinsic part of medicinal chemistry. Hardy chemists customarily tasted new syntheses to determine among other attributes, toxicity. Though replaced by machines in formal practice, so-called bioassays remained a constant in the research of psychoactive drugs, where it is often difficult to draw a line between the professional and recreational. Opium, LSD and many other drugs were extensively roadtested by their inventors. In 1799, Humphry Davy, the brilliant chemist and inventor, personally tested his first synthesis of nitrous oxide at Bristol’s Pneumatic Institute. Then he conscripted his friends to try out the euphoric gas, and to describe the effects in writing. Samuel Taylor Coleridge was among those who sampled the drug’s "unmingled pleasures". Coleridge detected "a warmth resembling that which I remember once to have experienced returning from a walk in the snow into a warm room."

More recently, Alexander Shulgin described the fun he and his wife had with psychedelics in the volumes PiHKAL: a Chemical Love Story and TiHKAL: the Continuation. The books are part lab report, part diary, complete with "dirty pictures" (as Shulgin describes the illustrations of molecular structure), and detailed descriptions of the effects at various dosages.

Today, anonymous online "trip reports", are lucidly informative, as well as delightfully esoteric: "[3-MeO-PCP] made me start crying from extreme feelings of reverence for Mark Twain". Others are hilarious parodies of the form – mundane slices of teenage life written in lab notation style – while a number are harrowing documents of addiction and self-harm. One haunting report is apparently written by a mother shocked to discover her son’s online habits after he died of an opiates overdose.

I first met Simon, the MXE sampler, at a Kew Gardens exhibition of psychoactive plants. He was wearing a T-shirt with the words, "Legalise Illegal Stuff" emblazoned on an Adidas logo. Skinny, with wavy blonde hair and intense blue eyes, he informed me: "I’m what’s known as a psychonaut.". A few weeks later, we met up at his local just outside London. Over some craft beers – Simon is a connoisseur – he described how he makes his own drugs as a hobby using equipment, raw ingredients and expertise obtained from the internet. Until recently he had a good contact to help with the crystallisation process. "Unfortunately he’s inside at the minute," he says.

He now buys items he can’t manufacture himself online from a lab in eastern Europe.

Given that over time he’s hoovered up a total of 39 different substances, he’s in pretty good shape. There’s a hole burned into the top of his left nostril, from a bad batch of homemade cocaine, and a singed eyebrow has regrown a little wonkily. Other damage may be percolating away under his now 22-year-old skin.

"I’ve had quite a few problems with depression and anxiety sort of thing," he says. "You’ll see I’m very shaky, from basically doing drugs I shouldn’t have done."

He shows me his hands, which shake like gyro mixers. But things could be much worse. Some friends have been consumed by drug use.

"I know lots of bright people who are shells of themselves from ketamine. You can’t have a conversation with them, they’re just not there," he says.

If Simon is an intrepid explorer of altered consciousness, this reporter is a timid mental shut-in. Cursed with hypochondria, I lack the nonchalance for successful drug-taking. In one high school experience I accidentally sent several grams of weed flying around a friend’s car, Woody Allen style. Though humiliated, I was secretly happy to not have to make good on getting high. However, it seemed wrong to continue my research without even leaving the house, pyschonautically speaking. So I decided to try a branded legal high product – the sniff’n’pray, pint of slops end of the drugs industry.

At UK Skunkworks, a head shop on London’s Holloway Road, I join the queue and scan the offerings, while an older customer regales the shop assistant with a spoken-word recital of the Pete Seeger song, "Turn! Turn! Turn!". To comply with new regulations, powder chemicals are now kept under the counter here, so the assistant insists I ask for what I want by brand name and, in compliance with the medicine act, there is no sales pitch. I leave with Lady B’s and Pink Panthers, both marked as not for human consumption. I make a plan to meet up a few days later with a friend; and post samples of what I have bought to an anonymous testing service, the Welsh Emerging Drugs & Identification of Novel Substances project (Wedinos).

The Wedinos lab occupies the attic floor of converted nurses’ quarters, on the grounds of University Hospital Llandough, outside Cardiff. Chief toxicologist Alun Hutchings’ office is a former bedroom, measuring 10 square feet. The main lab made of two bedrooms knocked through, and several more single bedroom labs down the corridor. The whole floor is filled with the whirr of powerful machines. "Best thing about this place is the view," says the softly spoken Welshman. "It’s less than ideal."

Wedinos is a charity established in 2013 to test samples of legal highs, anonymously and for free. Hutchings and his team receive envelopes and jiffy bags of drugs in the morning post, test each compound and post results on the Wedinos site, usually on the day of receipt. Though a twitchy steroid user once turned up at the door demanding they return his sample, Hutchings and his team generally work away in isolation here at Llandough.

Most drugs take just six seconds to identify on Hutchings’ lab equipment. A tiny sample is run through the time-of-flight mass spectrometer, or TOF, that flings the substance into a vacuum, measuring its weight by how fast it flies through the frictionless air. Software then checks this precisely measured weight against the thousands of drugs on a database.

If the TOF fails to identify the compound, other machines down the hallway can help narrow down the search, but an entirely novel substance must be taken to Cardiff and Vale Hospital for Nuclear Magnetic Resonance testing. This will give a molecular definition for the drug.

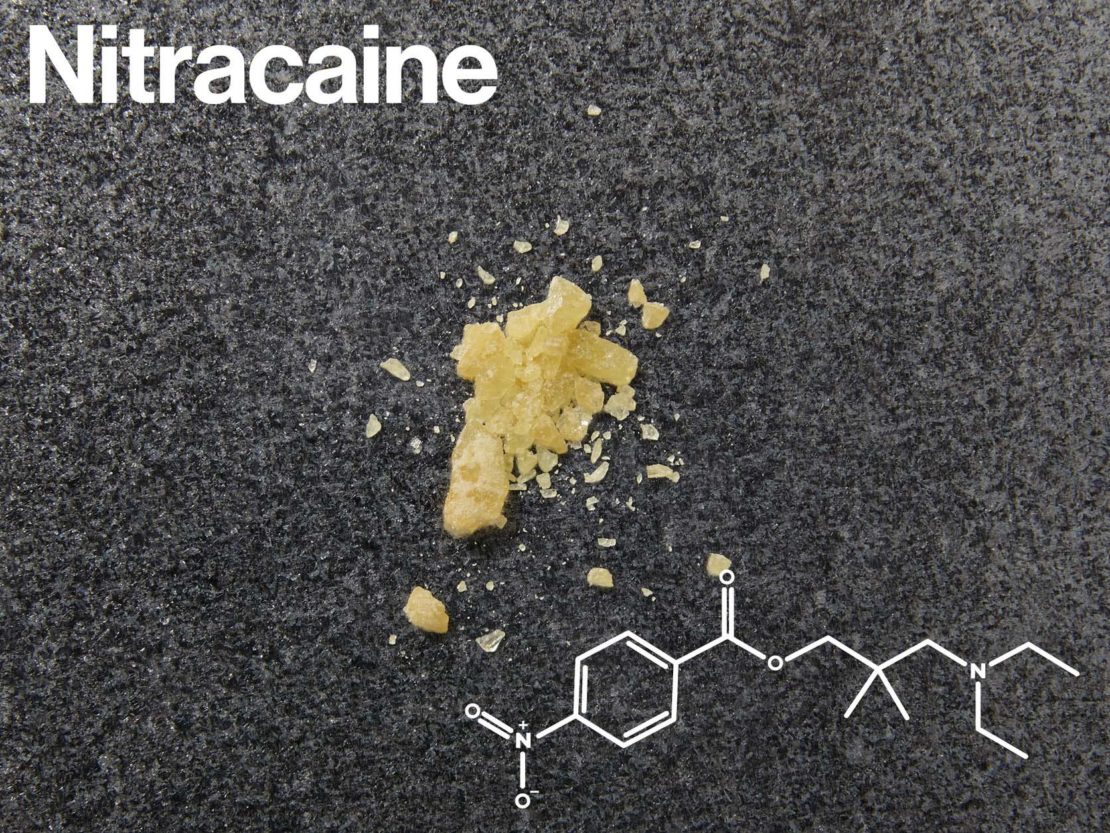

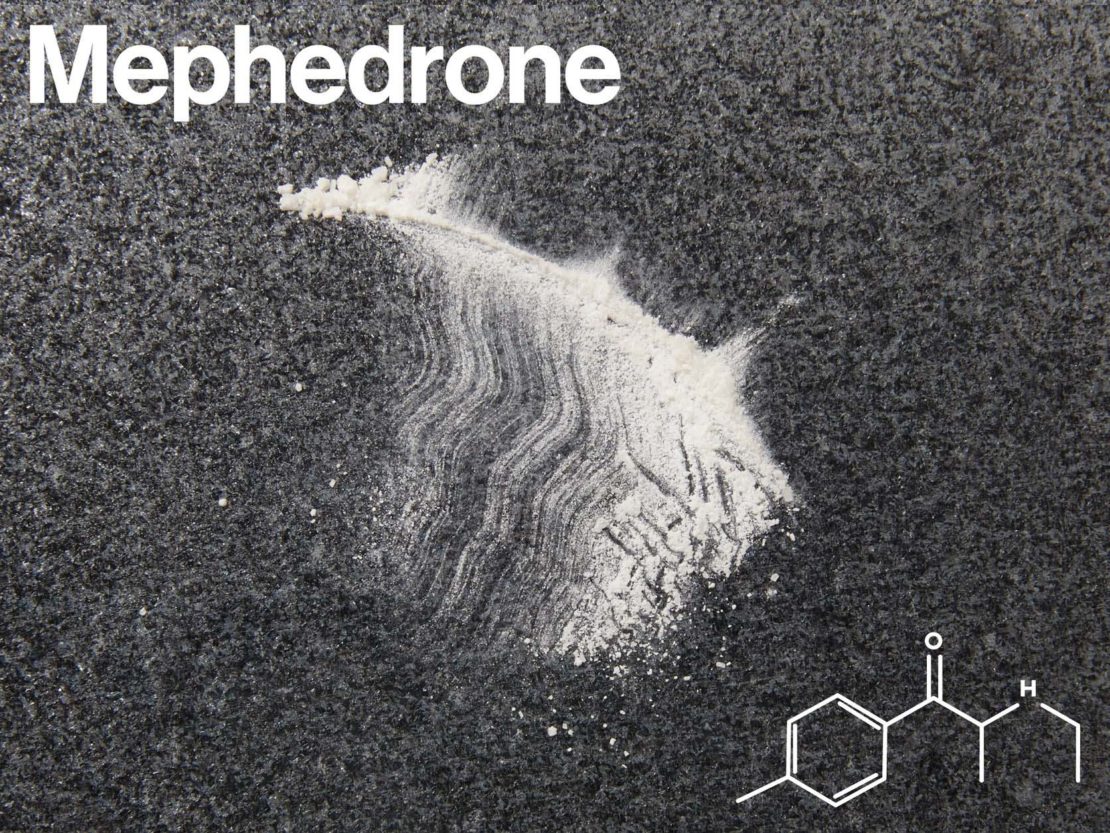

Recently Hutchings has tested several samples of synthetic cannabis that have been laced with embalming fluid, which contains methanol – Hutchings guesses it’s added to give an initial alcohol rush when smoked. Other samples reveal strange mixes of psychedelics and stimulants. One sample he dealt with was 4-methylmethcathinone, or mephedrone, which had been mislabelled as leucine, an amino acid generally used by bodybuilders, with wildly different toxicity.

"Take two grams of [mephedrone] and it’ll kill you," he says, "I thought that was particularly dangerous."

Explore

Who wants to live forever?They regularly receive dud submissions like used syringes; and recently, analyst Mia Riddle opened what looked like an empty cigarette paper which turned out to contain traces of heroin. (Sending controlled substances in the post is illegal and discouraged by Wedinos.) Riddle examines the new submissions each day, looking for familiar handwriting, recurring postcodes, or anything that might suggest a dealer is using Wedinos to advertise the quality of his product. If Riddle does flag a sample, it becomes a fishing expedition. Expecting to see their results online, the sender often gets in touch by email. Typically Wedinos then refers them to services like Harm Reduction Works.

Nevertheless, scams do occur. Wedinos was used by Scottish legal highs site researchchemistry.co.uk to test a dozen or so samples and post the results on a forum.

According to "Blodwyn", who runs the popular drugs forum UK Chemical Research, "Where there may have been doubt around a specific vendor or product, Wedinos has been invaluable in providing information that can without question prevent harm."

"If you read the forums you get the impression we’re doing good," says Hutchings. "You see people saying 'I’d never consider doing anything I hadn’t sent to Wedinos,' you know. But we’ll see."

The Daily Mail, though, has accused the organisation of providing a "kitemark" of quality for drug suppliers; and Conservative Welsh assembly MP Darren Miller has said its existence showed Labour in Wales have "given up on drugs."

But Hutchings doubts a legal highs ban would remove the need for an organisation like his.

"There’s a long history of people using substances to get high," he said. "You can close down the head shops, but that’s not going to stop you buying things off the internet. I don’t see how you can control the internet. You did that, there’d be the dark web. People will find a way."

Indeed people already have: on the dark or deep web, popular once-legal highs such as MXE or mephedrone continue to do a good trade on marketplaces trading in cryptocurrency, and accessed via the anonymous TOR network browser.

And even here there’s a counterpart to Wedinos: an underground harm prevention lab managed by Fernando Caudevilla, a Spanish physician who goes by the online name Doctor X. A family doctor in Madrid, Caudevilla runs the service through a laboratory at Energy Control.

For €50, payable in Bitcoin, Doctor X will test drugs bought on the deep web, running the sample against a database of 3,000 substances.

Energy Control has received more than 120 samples of drugs bought on the dark web since it began in April. I asked Caudevilla about the most alarming results.

"We have detected some mixtures of cathinones (stimulants like mephedrone) or mislabelled substances," he says. "But in general, the purity of dark web purchases is high and scams are rare, at least in our results."

Caudevilla says all proceeds go back into the service and that most Energy Control staff are voluntary. Doctor X also offers free advice on the marketplace forums, though it comes with a liberal dose of sass: "All drugs are absolutely harmless," he posted on the Silk Road forum. "If you leave cocaine, MDMA, meth or 4-AcO-DMT on a table, they won’t try to assault you, rape you or hit your balls."

While the FBI shut down the Silk Road 2.0 marketplace in November, forcing Caudevilla to suspend his advice service, the doctor is actively exploring new markets. He thinks the suggestion that his efforts encourage and enable drug abuse is like claiming the provision of condoms facilitates sexual promiscuity. "It’s the same kind of simple, stupid argument," he says.

"People don't need new drugs," insists David Nutt, the renegade psychopharmacologist who was fired as chair of the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs in 2009 for his opposition to drug prohibition.

He argues drug laws have inhibited the medical research of psychoactive drugs, and recently described the paucity of clinical research into psychedelics as "the greatest missed opportunity in the history of medicine".

Meanwhile, Nutt says, novel psychoactive drugs only exist to fill a void. Drug reform would eradicate that demand.

"Why do we have Spice (synthetic cannabis)? I don’t think people would smoke it, if cannabis wasn’t prohibited,” he says.

He plays down the scale of current risks.

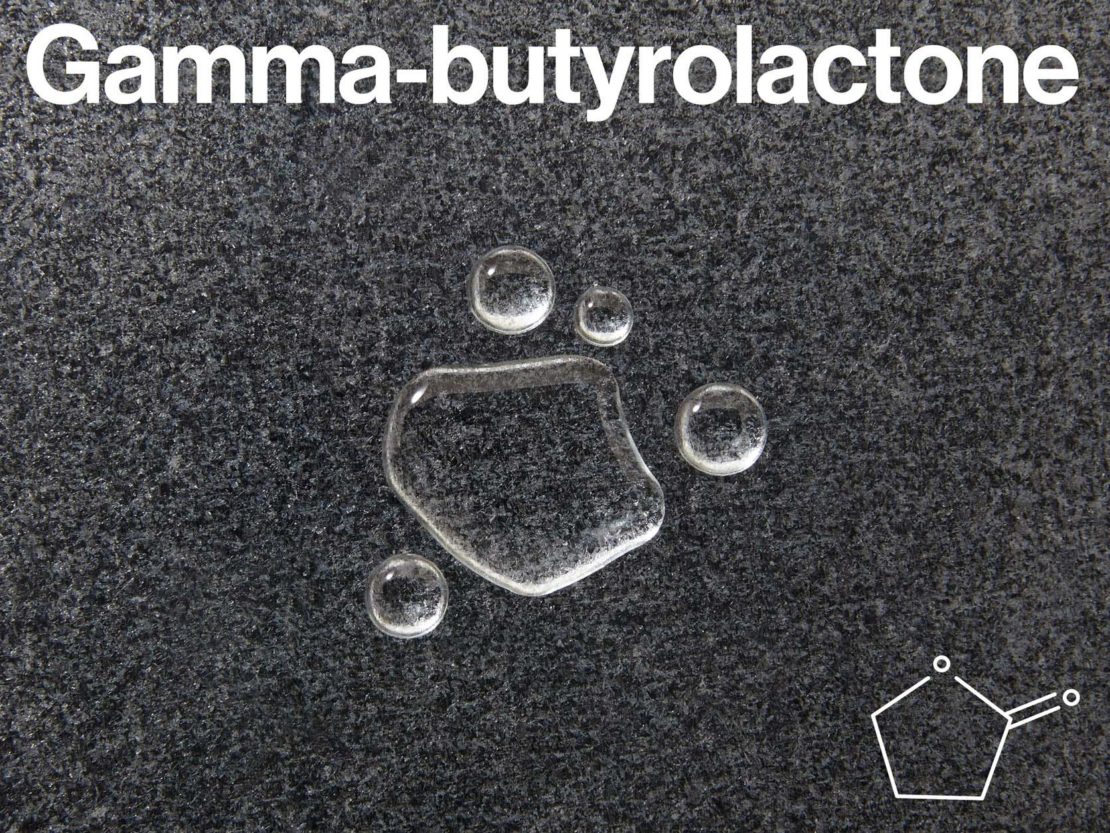

"There are very few deaths from legal highs; it’s hysteria," he says. "People who take new drugs are mostly psychonauts: they’re a small bunch who tend to know what they’re doing. The problem is others who get swilled, then try opiates or GHB. The leading cause of death in the UK for males between 16 and 50 is alcohol. Leaders have a moral duty to make drugs less harmful than alcohol available."

But John Ramsey, head of TICTAC Communications, a commercial organisation that tracks and identifies emerging drugs, says drug use in which the customers are guinea pigs will always be treacherous.

"It’s incredibly dangerous; it’s more by good fortune than anything else that we haven’t had a disaster. The people who make them are experimenting on young folks."

In this experimental climate, one New Zealander sees an opportunity for seismic change in the way we consider drug-taking. Matt "Starboy" Bowden envisions a world in which we get our substances from licensed distributors according to our unique profile, with clinicians at the point of sale. Bowden, who prefers the term "social tonics" to the D-word, is a prog rock performer, a steampunk fashion enthusiast, and a dealer known in New Zealand as the Godfather of Legal Highs.

"Islands are where innovation happens," says Bowden, when I reach him by phone. "We’re probably the most isolated place in the world. We’re a pragmatic people willing to try new solutions out."

For prescription drugs, securing regulatory approval is a decade-long headache of controlled, double-blind and randomised studies; and staggering costs: in the US it can cost billions for each new drug. In Britain, even once a drug has been approved, under the "yellow card" system, doctors can flag its adverse effects at any time.

“Let’s put our drugs through the same standard battery of tests that new clinical drugs are subjected to,” Bowden says. He operates a laboratory in Auckland where he and his team of chemistry graduates are searching for a narcotic elixir; a compound that gets you high, that they can prove is non-toxic, non-addictive and unlikely to cause death.

New Zealand has proven to be a prime market for legal highs. So remote and sparsely populated that international drug dealers tend to overlook it, the country has a methamphetamine problem to rival the worst in the world. A company called MethMinder is doing good business providing equipment to detect domestic meth labs. Bowden says New Zealanders are looking for less addictive and damaging alternatives to meth, ones that don’t breed organised crime.

In 2013, New Zealand hit on a progressive solution, along the lines Bowden proposed: licensing. The New Zealand Psychoactive Substances Act, 2013 theoretically allows a company to sell "low risk" recreational drugs with a license, once they have passed safety tests. The Economist hailed it as a "new prescription", better than Britain’s approach of trying and failing to ban designer drugs.

Explore

My first chemistry setBowden wants to build a predictable, safe and legal business, with an evidence-based approach to regulation, based on harm reduction. He believes New Zealand’s experience with legal highs hints at a huge demand for safer drugs. A study estimated that 400,000 New Zealanders took 26m party pills over eight and a half years, with no fatalities. It also showed that 44 per cent switched from using illicit drugs to "mostly just using party pills".

"Given the chance, people trend towards safety," concludes Bowden. "People don’t want to spend their weekend on the phone hooking up with some gangster, get stood over, raped, caught up in a drug bust, given dodgy stuff."

But much of the utopian fervour has already left New Zealand’s legislative experiment. The government issued 41 temporary licenses for a selection of substances as a good faith measure in 2013, then earlier this year suddenly revoked them all. Legal high producers have been banned from animal testing, further complicating the task of people like Bowden. No one has officially defined the term "low risk". New Zealand’s Prime Minister John Key said it would be "no bad thing" if the legislation ultimately blocked all new drugs. Still, Bowden is hopeful. People will always want to get high.

"Since the dawn of time, people have used social tonics. For social interactions, for relations – and reproduction. They are very important. Humans are going to keep doing that," he says.

"We’ve tried 'Just Say No'. That’s not going to work anymore. Drug use is a lot like gay marriage – you might not do it yourself, but [would you] send someone to jail for it?"

The samples I sent to Wedinos return mixed results. While the Lady B’s I picked up at Skunkworks do indeed contain a psychedelic, there’s a major presence of benzocaine: a numbing agent often used to cut cocaine. The Pink Panthers contain methiopropamine, a little-known upper, first synthesised back in 1942. The medical literature remains eerily silent on methiopropamine, but the World Health Organisation says it is "of especially serious risk to public health and of no recognised therapeutic use to any party." No clinical human trials have been held on it, but it has been implicated in several deaths, and anecdotal evidence suggests it poses myriad health concerns. Insomnia, chest pains and vasoconstriction – in which the extremities turn blue – are among the most common reported side effects. One user complains of a "faint whistling with each heartbeat."

The night before the experiment I lie in bed, riddled with anxiety. I fret about Hutchings, the Wedinos toxicologist, and whether I am abusing the service. No doubt he’ll assume I’m writing an article about drugs as an elaborate ruse to get wasted. I consider the true psychonauts such as Alexander Shulgin fearlessly exploring the farthest reaches of the mind and plotting their course for others with scientific rigour.

I’ve never even tried a psychedelic, unless you count nutmeg (at below threshold dose), and these obscure compounds are surely not the place to start. Also, the 14-hour trips promised by Lady B’s sound impractical for a weeknight, so I decide to strike off the psychedelics and I turn, grimly, to the stimulant, Pink Panthers.

Before a friend and I take the substance, I phone Simon, the psychonaut, hoping for a soothing, pre-game pep talk. He hasn’t even heard of methiopropamine, and sounds generally unimpressed with the idea. "Little doses," he offers, doubtfully. I hang up, gripped by panic. Simon once snorted an entire baggie of synthetic caffeine for a dare. What chance do I have?

We take the Pink Panthers just before 8pm. Almost immediately, I feel wobbly legged and a little nauseous. We brave the rain and head to the pub, where my friend chats excitedly and reports a palpable buzz. For me, well, perhaps my anxiety is obscuring more positive results. There is a general numbness around the face and I am acutely aware that rainwater has seeped through my shoes and is dampening my socks. The urge to re-dose is profoundly absent. With the Pink Panthers wearing off, my friend declares the experiment abandoned and orders another beer. On the way home from the pub, I toss the remainder of our stash, resigned to the finding that my personal laboratory is not fit for purpose.

Some names have been changed for this piece