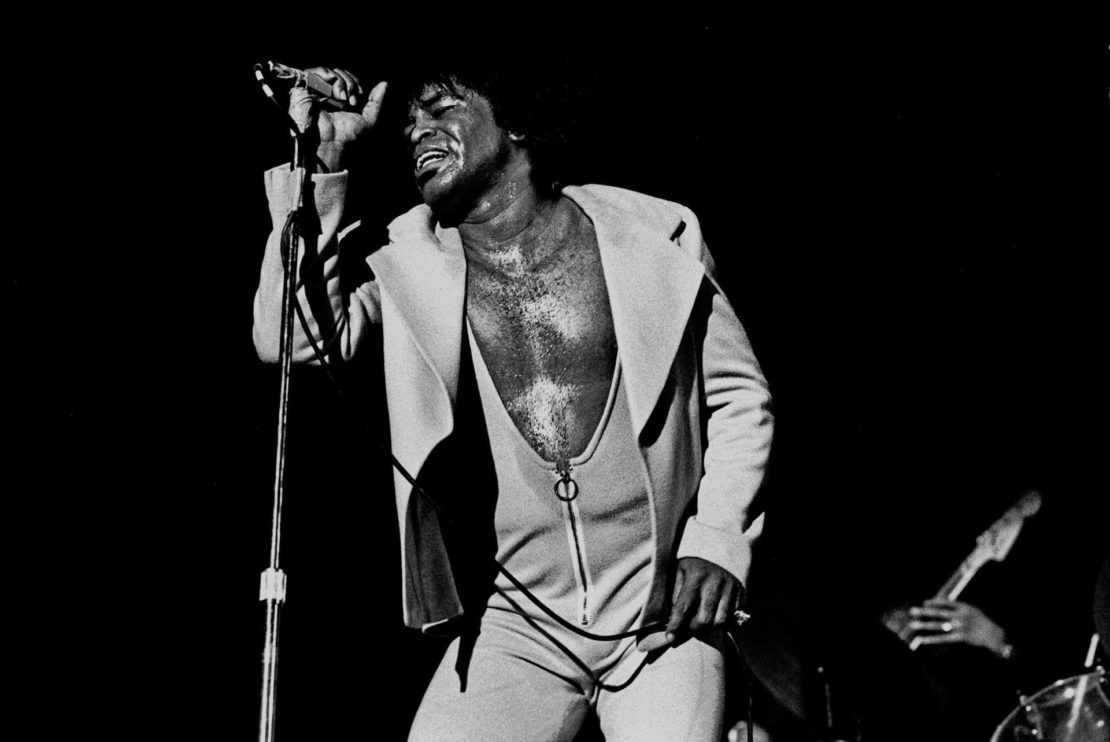

Dance moves: James Brown's single-handed invention of funk

"The one thing that can solve most of our problems is dancing," is James Brown's most famous quote, and is certainly the most germane to our interests. (Well, apart from maybe "Hair is the first thing. And teeth the second. Hair and teeth. A man got those two things he's got it all.")

James Brown was a rare instance of a first-class showman who was also a real-deal innovator – the missing link between Louis Jordan, who influenced him, and Prince, who he influenced.

Unlike Prince, who, almost off the blocks, seemed little like anything else, James Brown had spent 12 years in the industry as a consummate R&B professional before he dragged into the world his most famous creation: funk.

Listen to an audio version of this article, brought to you by Curio.io

Brown's the Famous Flames had rushed into filling the space vacated by their idol Little Richard when the flamboyant rock 'n' roller retired from secular music in the 1950s (quite literally – the young group were booked to replace Richard on tour following his sudden conversion to preacher following a near-death experience while flying over Australia).

The group's slick combination of R&B, soul, doo-wop, and rock 'n' roll coexisted alongside Brown's solo career in the early part of the 1960s. If the transition from vocal quartet leader to dance music innovator can be pinpointed with any accuracy to one event, then it would probably be the release of the Out of Sight/Maybe the Last Time single in 1964.

Both sides were composed by Brown under his publishing pseudonym Ted Wright, but while the gospel-ish Maybe the Last Time represented the final recording from the Famous Flames, Out of Sight was a solo Brown recording that gestured towards a new evolution in his sound.

Brown said of the recording:

Out of Sight was another beginning, musically and professionally. My music – and most music – changed with Papa's Got a Brand New Bag, but it really started on Out of Sight… You can hear the band and me start to move in a whole other direction rhythmically. The horns, the guitars, the vocals, everything was starting to be used to establish all kinds of rhythms at once… I was trying to get every aspect of the production to contribute to the rhythmic patterns.

Funk was just around the corner. Out of Sight was built around a stuttering, looping rhythm and blasting horn refrain. The recording marked the first collaboration between Brown and the man who would be one of his funk generals, saxophonist Maceo Parker. Though not featured on the recording, you can see the Flames slicing some furious rug to this dance tune in this legendary 60s TV clip:

Brown had tentatively tried out a similar sound, two years earlier, on the B-side to his 1962 R&B hit Three Hearts in a Tangle. The song, I've Got Money, is a sort of loose sketch of a could-be funk. In his 2012 biography of Brown, the writer RJ Smith describes the tune as:

… a song whose time has yet to arrive, and it's barely a song. It’s like a blueprint of some uncanny object. It's an assemblage of parts: a scimitar guitar chord coming down on the One, a show band horn chorus quoting Judy Garland's "The Trolley Song", and [Clayton Fillyau's] stampeding drums. The parts are arranged in a line, one beside the next – an incomprehensible rebus.

Both songs were experiments in a different way of thinking about rhythm in US chart music. They were repetitive, aggressively danceable, and ride heavily on an African-influenced groove.

Brown would return to Out of Sight a year later, recasting it as the even more groove-insistent Papa's Got a Brand New Bag.

"Papa's Bag was years ahead of its time," Brown wrote. "I was still called a soul singer, but… I had gone off in a different direction. I had discovered that my strength was not in the horns, it was in the rhythm. I was hearing everything, even the guitars, like they were drums. Later on, they said it was the beginning of funk. I just thought of it as where my music was going. The title told it all: I had a new bag.”

Funk had arrived, and it was a new kind of musical fury.

Later on, they said it was the beginning of funk. I just thought of it as where my music was going. The title told it all: I had a new bag

Brown would spend the next 10 years honing this style to the point of perfection, abandoning it only when the rising force of disco represented too much of a threat to his career to be ignored.

But in the 1960s, funk was a white-hot force – political, danceable and capable of transmuting social disfranchisement into ass-kicking grooves.

One of the main musical tweaks that Brown had made to his music in order to accommodate his new rhythm vision – and which became one of the defining quirks of funk – was to put an overwhelming emphasis on the first beat of the measure. You can hear this in Papa's Bag, and Brown would drill his band to kick into this rhythm with the famous command "on the one!"

In compositional terms, what Brown had done was switch from the shuffle rhythms and 12/8 time signatures of his earlier work to 4/4. But whereas 4/4 in soul music traditionally had a one-two-three-four backbeat, Brown's funk had a one-two-three-four kick, with electric bass, syncopated guitar and Afro-Cuban drum patterns clicking into interlocking parts rather than accompanying each other in traditional harmony.

Sign up to our newsletter

Or, to put it another way, by making each instrument in his band into a drum, Brown had reorganised his music into a percussive grid, where each musical voice was required to make simple but precise contributions in order to keep the all-important rhythm rotating.

This early funk would often just require players to blast one- or two-chord vamps at appropriate intervals, rather than contribute fluent melodic lines, and although this sounds like a simplification, it was a musical transition that even musicians of the James Brown Revue’s calibre struggled with.

Most read this month

Fiction: Divided we stand, by Tim Maughan How Scotland is tackling the democratic deficit The Long + Short has ceased publishingThere is also some contentiousness around the extent to which Brown can claim authorship of these compositions. Famous Flame Bobby Bennet claims "James Brown did not write anything", and that he aggressively stole writing credits from his band and musicians around him, alleging that even Papa's Bag had been penned originally by Brown's former cellmate and occasional Flame, Johnny Terry.

It is true that Brown couldn't play any instrument particularly well – although he drummed in an early iteration of the Flames – and that most of his composition consisted of issuing sometimes unorthodox verbal instructions to his band as they were playing.

Brown's bandleader and arranger during his most solidly 'funk' phase of his career – the late 1960s – was saxophonist Alfred 'Pee Wee' Ellis , who remains more enthusiastic about Brown's songwriting process, which involved a kind of structured group improvisation:

The improvisation was designed by James Brown. He chose who he wanted to improvise, and mostly, it was Maceo. The guitar player had a little room, and I had a solo once in a while. But most of this stuff was designed by James Brown. He decided how a song would be formed, and what would take place within the song. If he felt comfortable with it, he would stretch it out, so he could grunt and do his dances and so forth.

"The band was disciplined," Ellis added, "and we could interpret his movements. If you were on a section of a song, it wouldn't change until he did a particular movement that signalled the change. So we would just stay there and roll on."

This band figurehead-as-author approach would be replicated by many of the bandleaders who followed in Brown's wake, most notably Fela Kuti, who Ellis claims Brown also admired.

Brown's vocal contributions were also largely spontaneous – his screams and grunts were deployed using the same "everything is percussion" logic that drove the polyrhythmic band. It was new, exciting and bizarre enough to white and non-American audiences that, by 1966, Pete and Dud had attempted their own parody of Papa's Got a Brand New Bag on Not Only But Also:

Though Brown was the eminent leader of the new funk sound, our playlist of funk's origins demonstrates how musicians like Jackie Lee, Don Covay (formerly of the Little Richard Revue), future Beatles and Rolling Stones keyboardist Billy Preston, Rufus Thomas, Jr. Walker & the All Stars, Laurel Aitken, Leon & the Burners and – perhaps most notably – The Bar-Kays were significant early adopters.

Over the coming decades, funk would splinter into an assortment of child genres, some of which have retained credibility (P-funk, electro) while others are considered aberrations (funk metal, funk jam).