Dance moves: the parties and happy accidents that gave us house music

Before house was a style of music, it was a style of partying. Of course, it wasn't called house then – a weird name, attributed to an array of sources including a Chicago nightclub, The Warehouse – but the genesis of the scene was in exclusive, invite-only disco-slash-listening parties of the early 1970s. At the forefront was David Mancuso's Love Saves the Day party in Manhattan at his illegal club space, the Loft.

Mancuso, who died aged 72 on Monday, would invite a diverse group of gay men to his parties, where he played the black dance music that he had such affection for. He had an eclectic DJing style, mixing diverse Babatunde Olatunji in with James Brown, Cameroonian jazz and obscure Congolese hymns. Alcohol was not served at the Loft, just punch, fruit and candy – and the space was adorned with children's party and Christmas decorations. Central to the experience was Mancuso's state-of-the-art, boutique sound system.

Two regulars at the Loft were a pair of teenagers named Larry and Frankie, who had bonded through the New York drag scene over their shared ambitions to become fashion designers. Larry briefly dated Mancuso, but it wasn't until another Loft regular, Nicky Siano (who would later become resident DJ at Studio 54), employed Larry and Frankie to decorate his new club, the Gallery, and distribute punch and acid to partygoers, that the two youngsters began to take an interest in being behind the decks themselves.

Siano – who also had an affair with Larry – taught the pair his experimental DJing style involving three turntables, which he would use to extend tracks in bizarre and imaginative ways while repitching and segueing other records seamlessly in and out of the mix.

This harsh and disturbing, liquid and rippling machine noise didn't sound like anything else: it was the basis for a whole new kind of music

Frankie, born Francis Nicholls, then became known by the name Frankie Knuckles, and Larry – Lawrence Philpot – became Larry Levan. The latter, in particular, quickly got attention around the city thanks to his flamboyant, personality-driven style of DJing, eventually leading another Loft fan, Michael Brody, to open a club specifically built around the cult of Larry Levan as a DJ.

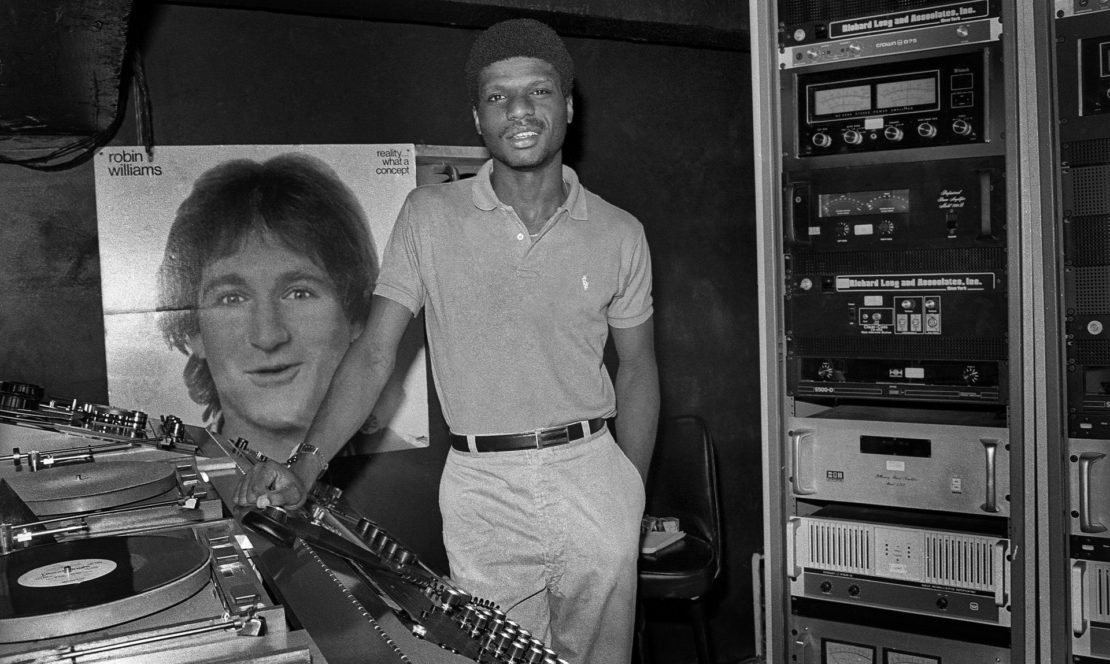

Levan was the house DJ at this club, the Paradise Garage, from 1977 to 1987, and this is exactly where and when house music germinates.

He channelled his 'diva' personality from the drag days into his sets. Levan wouldn't just take risks with mixing weird combinations of dance records, he would toy petulantly with the controls at his disposal – rolling off all frequencies except the bass, which he would yank all the way up to 10 so that the walls shook, only to then do the same with the treble until the clubgoers had piercing headaches. He might loop a small vocal segment of a record for hours on end, forcing his captive audience through the pain of the repetition until it became something transcendent and mantra-like. If he was heartbroken, he would make sure his audience knew it, slamming huge tearjerker ballads or acapellas down in the middle of peak dance sets. If he was angry, he could also smash records together in a discordant, aggressive manner that would make disciples of beatmatching feel queasy.

For almost any other DJ, this mercurial trickery would cause walkouts, but Levan would play to an always sold-out crowd for 12 hours at a time. The awe that surrounded him bordered on the religious, so much so that his sets became referred to as 'Saturday mass'.

Levan also began to introduce synthesiser players and drum machines to the Garage, which he would mix in and out of his DJ sets as they were playing, eventually leading to the formation of a Paradise Garage house band – the Peech Boys. The Peech Boys recorded the house classic Don't Make Me Wait, built around Levan toying with studio delay and the then-rarely used 'handclap' sample on the LinnDrum.

Levan's heroin problems, bust-ups over money and credits to other musicians, alongside the fact that he spent a year tinkering with the mix of Don't Make Me Wait until it was finally ready for release in 1982, caused the group to implode. But that one single suggested a template for house – percussive, uplifting, soulful electronic dance music – that drew musical inspiration from Levan's record box, which contained everything from disco to gospel, Manuel Göttsching to Smokey Robinson.

Levan would go on to make a series of classic dance records, producing and remixing the likes of Arthur Russell, Loose Joints, Chaka Khan and Gwen Guthrie. The salient point here is that this was a music producer who learned his craft and pushed forward his own innovations not by mastering instruments or theory, but purely by playing records to people in nightclubs.

In parallel to the New York house productions of Larry Levan and Frankie Knuckles, another kind of house was leaking out of Chicago. The Chicago based Trax Records released Knuckles's music. Whereas the Detroit sound was all about the 909 drum machine, and the Paradise Garage had its LinnDrum, in Chicago they had another toy: the Roland TB-303 bass sequencer.

Many of Trax Records' biggest singles were built around the singular sound of the 303, a machine that had been developed by Roland for guitarists to use as bass accompaniment when they were practising alone. It was not successful in this purpose, and production lasted for just 18 months, between 1982 and 1984. In 1984 though, a Chicago DJ, Jesse Saunders, used a 303 to make a house track – the influential, hypnotic and minimal On and On. When the local Trax crew got their hands on the machine, they got the 303 to do weird shit.

In particular, they found that by holding down a repeating note pattern on the 303 and – rather than playing traditional keyboard sounding notes – fiddling with the cut-off, frequency, resonance and envelope modulation filters on the machine instead, the 303 would make unusual, distinctive squelching noises. This sometimes harsh and disturbing, sometimes liquid and rippling machine noise didn't sound like anything else: it was enough to form the basis for a whole new kind of music.

The 1987 Trax 12", Acid Tracks by Phuture, gave this new music – acid house – its name and sound. Instead of NY house's disco-influenced bass and and gospel vocals, this new house was moody and alien, often lacked identifiable key changes and the only singing was that squawking, chirruping, ever-modulating 303 talk.

But in a certain way, Acid Tracks was not the first acid house record. In fact the first acid house record wasn't actually an acid house record, it was an Indian classical one that accidentally landed on a similar sonic style. The record was made in 1982 with one prescient gimmick: it was an album of ragas done in a disco style.

Synthesising: Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat was a one-off novelty album by an Indian film composer and wedding musician named Chanarjit Singh. In the early 80s, producers were starting to use Indian disco songs as Bollywood film themes. Singh decided he should therefore branch into electronic music and bought three Roland machines, a 303, an 808 and a Jupiter-8 keyboard almost on a whim.

Most read

Why the world wide web will break up Is there such thing as a 'criminal' face? Are women the answer to our uncertain political times?He found that the 303's glissando lent itself well to performing ragas: the six tonal frameworks associated with different times of day that form the basis of Hindustani classical music. Because the three Roland machines could be synced together, and sounded good together, Singh realised he could set the machines up like a mini automatic orchestra and record his electronic ragas – his 'disco' ragas – in real time, so he recorded them and released them as Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat.

The album failed to make any impression in India and was quickly forgotten about by Singh himself, who continued his work as a film composer. In 2010, a Dutch record collector who had picked the LP up randomly in a record shop while visiting New Delhi, reissued Ten Ragas, positioning the collection as "the first acid house record".

Like Ryuichi Sakamoto's proto-grime and proto-electro songs, Ten Ragas is only acid house by pure coincidence. But it's more intriguing, because Sakamoto was a recognised tastemaker who would have understood modern dance trends, whereas Singh – a jobbing musician who usually recorded elevator renditions of popular tunes and who was perhaps clumsily trying to make a kind of spiritual music here – was bluntly unaware of electro, house or anything.

Yet Singh had abused the 303 and 808 in a way that was far enough out of the machines' intended remit to accidentally sound like the repetitive, unintentionally raga-like acid house sounds coming out of Chicago, but five years earlier.

The reissued Ten Ragas became an instant cult hit and Singh was bemused to find himself sharing the stage with modern dance music heroes like Lindstrøm, Carl Cox and Caribou before his death in 2015. A true outsider dance innovator.

More in this series

Dance moves: Race and the rise of ragtime, 1900-13

Dance moves: Blues explosions, 1914-17

Dance moves: How swing became the first pop music – and gave us the first hipsters

Dance moves: How northern soul led to club culture

Dance moves: James Brown's single-handed invention of funk

Dance moves: The first deejays

Dance moves: Riots in Lagos and the birth of electro