Dance moves: How Goldie made a break for it

In the early 1990s, dance music sought out harder sounds. The Dutch had the pulverising hardcore of gabber, while London club nights like Fabio and Grooverider's Rage were mixing house tracks with US hip-hop. This collision of house synths with the old-school funk breakbeats that were powering hip-hop gave producers new ideas.

Instead of leaning on drum machines for four-on-the-floor rhythms, rave producers began to sample breakbeats for their tunes: the flashy drum breakdowns in old James Brown and other funk and soul records. These breaks could be purchased on the Ultimate Breaks & Beats LP, compilations marketed as DJing tools.

In hardcore producers' hands, these breaks became ever-spiralling, self-imploding beat fractals that would create a careering, hectic, anarchic sound when positioned under blasts of rave synth.

Perhaps because of hardcore's innate irreverence for musical tradition, these breaks were not venerated as historical artefacts, but things to be ripped apart, stitched back together and then smashed into atoms. The result was a delirious, addictive pill noise, and it would achieve its zenith in one particular hardcore offshoot.

In the early19 90s, dance music sought out harder sounds

Where the term 'jungle' came from isn't quite clear. However, vocals and samples from Jamaican MCs were popular on early jungle tunes, which had a particular ragga bent, and the term 'junglist' – which referred to a denizen of the Jungle area of West Kingston – began to crop up on some of the records.

Although the early jungle records were as intense as anything in the hardcore scene, the fluid, shifting rhythms of jungle also had jazz connotations, and throughout the decade it would become increasingly more sophisticated and tasteful, resulting in a schism between the original ragga-tinged jungle records and the smooth, jazzy-soulful, Mercury prizewinning albums later in the decade, which became referred to as drum'n'bass.

Spotify playlist: early jungle (1992-93)

Again, the engine powering jungle was the break – and one break in particular. Today, Grooverider estimates that at least 70 per cent of all jungle and drum'n'bass tunes ever produced are built on the rickety, skittering foundations of the Amen break.

What is the Amen break? Think of the drum'n'bass sound – those drums. That's the Amen break. Jungle was a scene constructed around a core of dance producers scientifically investigating the sonic possibilities of one particular 6-second long drum sample from a 1969 funk B-side.

Over the course of drum'n'bass history, this break would be sped up, slowed down, played backwards and re-edited into myriad configurations.

Sign up to our newsletter

The break was from a track called Amen, Brother, recorded by an obscure funk and soul group called The Winstons – who, perhaps controversially, have never seen a penny from their break, which is now regarded as part of the public domain and therefore fair game for appropriation. The sole surviving member of the group, Richard L Spencer, who holds the copyright for the recording, even told the BBC that upon finding about the thousands of records based upon the break:

I felt as if I'd been touched somewhere where no one is supposed to touch. Your art is like your children, it's like a part of you. I felt invaded. I felt like my privacy had been taken for granted. And as a historian, as a social scientist, I also felt like the history of African-American music from the 1800s to the present is basically carted off by other people who became very wealthy and rich and we've usually been left out. You almost have to do like we did when we gave up Africa and just go… well, that's the way it is. I'm flattered that you chose it, but please make it a legal interaction here and pay me. The young man who played that drumbeat, Gregory Coleman, died homeless and broke in Atlanta, Georgia around 1996.

Eventually a crowdfunding campaign raised £24,000 for Spencer.

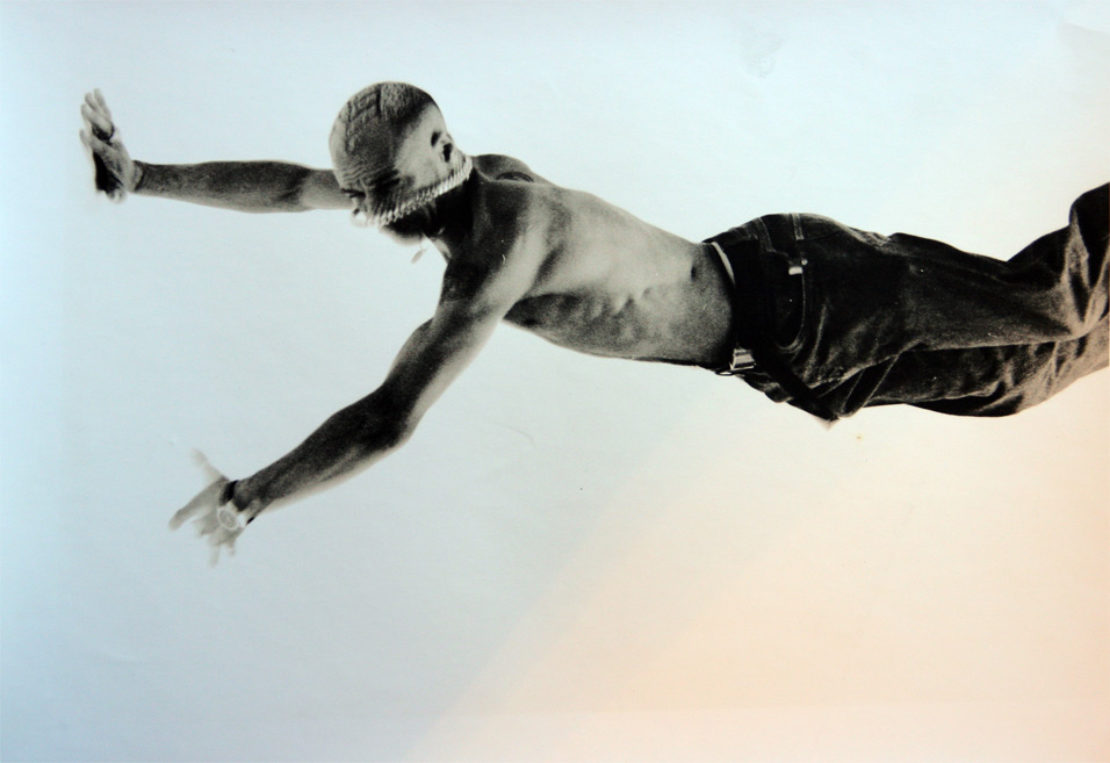

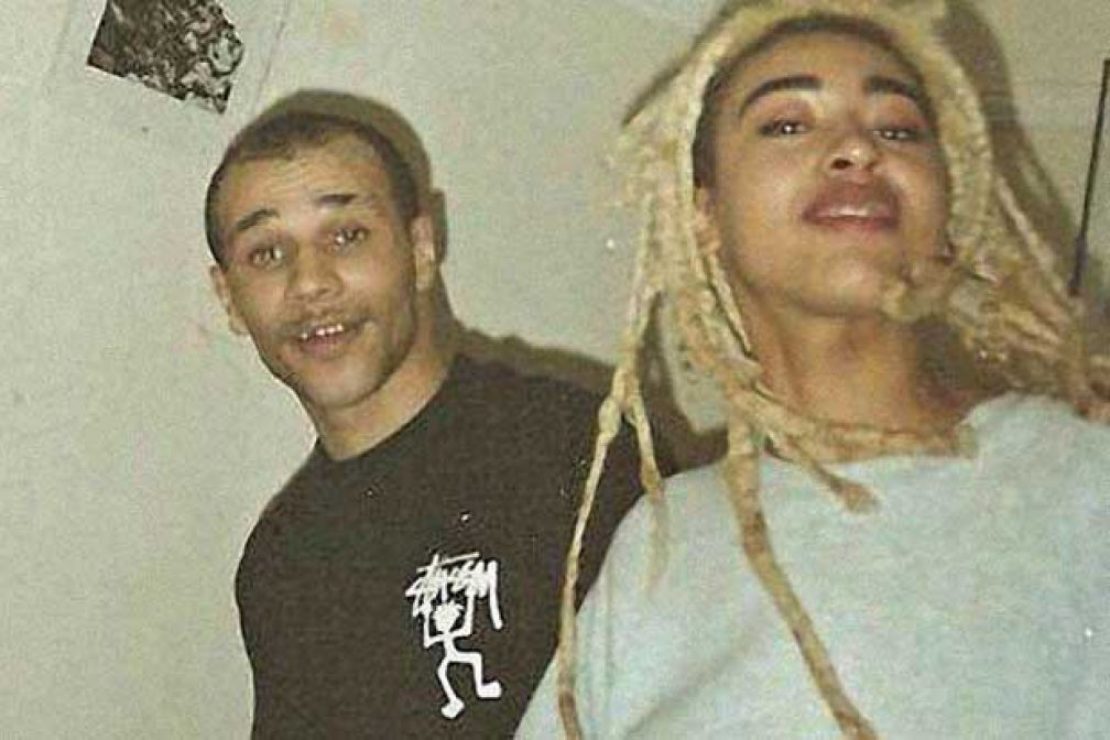

Perhaps jungle would have petered out, like its sister genre – breakbeat techno – and register now as a mere passing fad, had it not been for the charisma and ingenuity of its biggest star. Goldie was a graffiti artist and breakdancer from Walsall who had wound up in London after a spell of success in New York, bulletproof with confidence. It was this confidence that made him pursue an attractive girl he'd noticed around Camden, the DJ and producer Kemistry, who introduced him to her friends on the scene.

Goldie acted as a kind of artistic director crafting an elaborate, mind-bending collage

His mind blown by what he was hearing, Goldie quickly ingratiated himself, offering his services first as a graphic designer and artist. Although he had no previous musical experience, Goldie didn't see why he couldn't also make a record, and booked some time with a studio and engineer to do just this. He took a box of his favourite records and had the engineer fill up every bit of hard drive on two samplers, which he proceeded to re-order, intuitively directing the studio staff as to where each sample or loop should sit, until he walked out of the studio with a debut EP.

Goldie would repeat this process throughout his 90s output – acting as a kind of artistic director crafting an elaborate, mindbending collage – while a collaborator did the programming and mixing and facilitated the technical aspects of making a record under his dictation. In contrast to sound engineers or DJs who produced music, Goldie approached arrangements from a visual art perspective, and he pushed the music forward by demanding things that his more tech-savvy collaborators were resistant to because, being more aware of technological and musical limitations, they didn't think his ideas were practical or possible.

This persistence and self-belief twinned with an ambitious creativity led Goldie to make that rarest of things in dance music: a classic album. Timeless, made with producer/engineer Rob Playford of 2 Bad Mice, reached No 7 in the charts and is listed as one of the best albums of all time in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die. By his second album, Saturn Returnz, he was crafting hour-long orchestral drum'n'bass symphonies and collaborating with David Bowie. And then, eventually, he was writing actual classical symphonies, in-between appearing on Strictly Come Dancing and Celebrity Big Brother.

A version of this article was originally published on 20jazzfunkgreats

More in this series

Dance moves: How swing became the first pop music – and gave us the first hipsters

Dance moves: Race and the rise of ragtime, 1900-13

Dance moves: the parties and happy accidents that gave us house music

Dance moves: How northern soul led to club culture

Dance moves: Riots in Lagos and the birth of electro

Dance moves: Blues explosions, 1914-17

Dance moves: James Brown's single-handed invention of funk

Dance moves: The first deejays