Perfect pitch brewing

What some people might consider stagnation, others may prefer to call artistry, loyalty or tradition. And for those in the brewing or beer-drinking community there's no better example of the magic of maintaining tradition than the lambic brewing method. Take the Belgian Cantillon brewery, one of the best-known makers of this acidic, challenging beer style, which claims to be a place where "nothing has changed since 1900". The largely unmodernised premise boasts barrels as much as a century old.

Common commercial beer-making practice is to introduce a carefully considered dose of cultivated yeast to enable fermentation. For the bigger beer names particularly, keeping the taste of each batch consistent is the key; so standardisation is a crucial brewing component.

By contrast, in the world of lambics it's character not control that is the main concern. For the small cadre of traditional lambic brewers who occupy a unique beer 'terroir' – centred on the Zenne river valley near Brussels – the cooperation of indigenous, wild yeasts enables an organic, unpredictable process of 'spontaneous fermentation'.

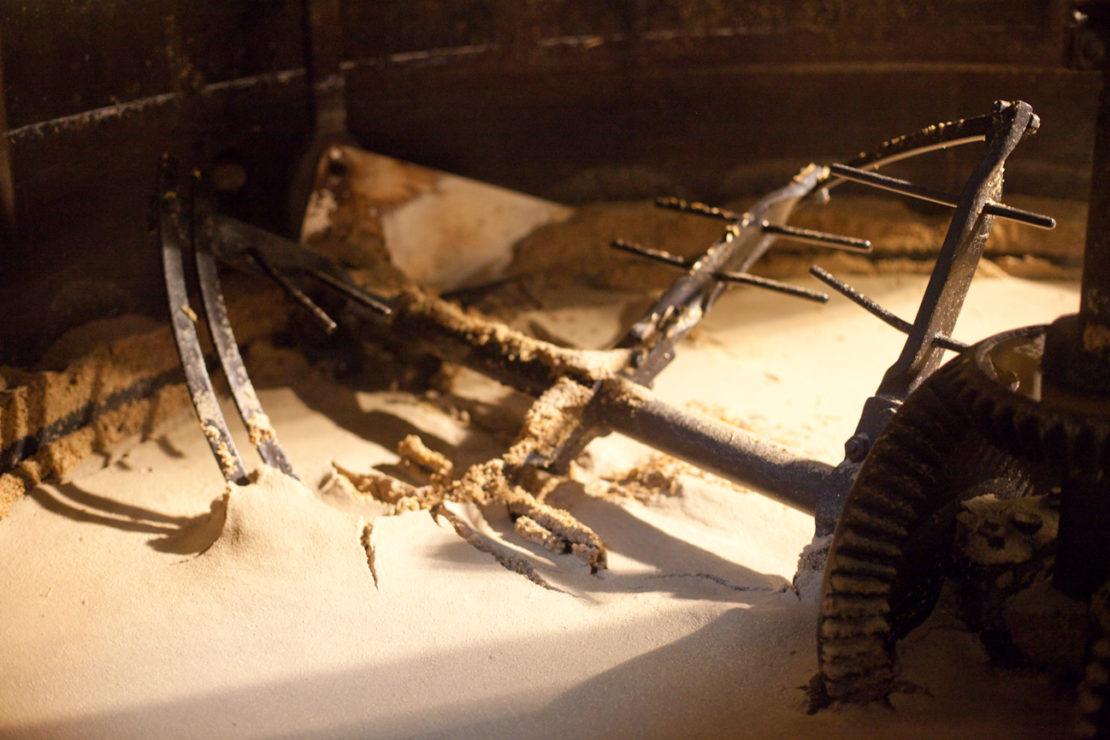

The process begins when hot wort (the product of combining water with malted barley, raw wheat, and boiling it with aged hops) is fed into shallow, open vats known as cooling tuns or 'cool ships', usually sited at the top of the brewery. As the beer rests overnight, local micro-flora float in – through open louvred windows, through minuscule gaps, or from the ancient roof beams and wooden floors themselves – to settle into the waiting liquid and effect a period of fermentation: a process known as pitching. Each brewing environment will have its own community of roaming yeasts and bacteria, and these are carefully shepherded to ensure that the environment contributing to their particular character is as undisturbed as possible.

The fermentation process continues once the liquid is then transferred to wooden casks – themselves home to a collection of native yeasts and bacteria – in which the lambic will age for up to as many three years; and where a further, complex period of fermentation will take place.

Finally, the beer that emerges from the casks is dry and flat with an assertive, tart taste. Pure lambic can be blended to produce Gueuze, which is often used as a base for fruit beers, or sweetened or spiced to create a Faro.