What Ralph Nader taught us about car safety – and the virtue of red tape

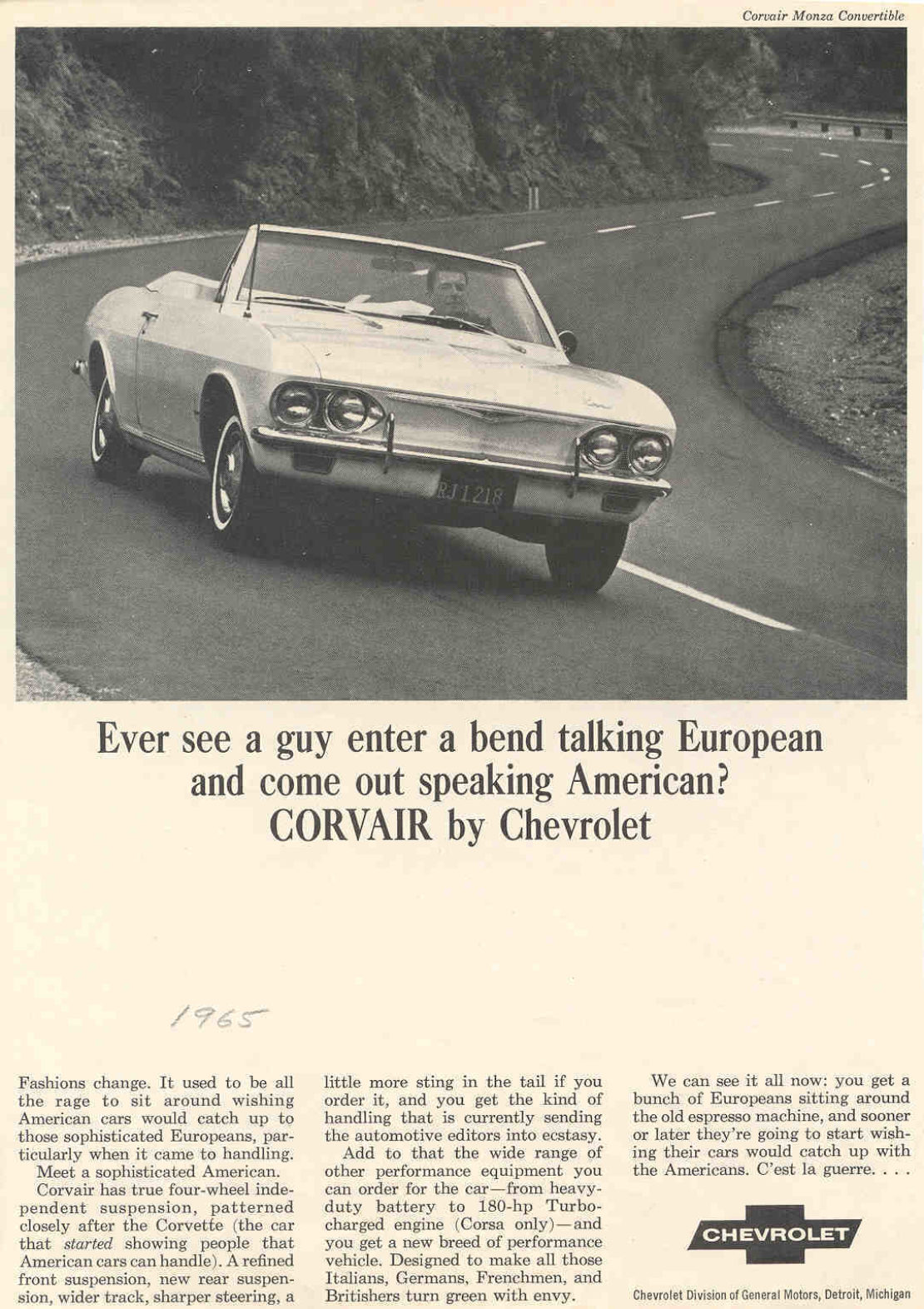

"You are about to meet a true international beauty, with a shape that blends elegance and excitement," intoned the golden voice of a television advert for the 1965 Chevrolet Corvair: "There is no feeling in all the world like the one behind this wheel."

Yes, America, bless its heart, had fallen head over heels for the automobile, and automakers like Chevrolet knew it. Mid-20th-century automobile advertisements promised horsepower, styling, and the allure of the open road. One even promised to turn Europeans into red-blooded Americans.

Yet, like many love affairs, America's mid-century infatuation with the automobile was proving destructive. In 1965, the same year that Chevrolet released its new Corvair, 49,000 Americans would die in automobile crashes: nearly as many as the total number of American soldiers who would die in the entirety of the Vietnam War.

In November of that year, Ralph Nader – yes, that Ralph Nader – would bring this harsh reality to the attention of American drivers with the publication of his book, Unsafe at Any Speed: the Designed-In Dangers of the American Automobile.

The book inspired action in Congress – and quite vociferous objections from automakers – leading to the passage of numerous enhanced safety regulations as well as the creation of a new regulatory agency to enforce them. By 1980 the number of deaths in automobile crashes had decreased considerably. Yet what is more interesting is that, despite near-constant complaints from automakers that regulations would hinder growth and stifle innovation, the new regulations actually helped force innovation and American automakers to produce cars that were not only good for passenger safety and the environment, but for profits as well.

Following Donald Trump's recent (dare we say unrealistic) declaration that he hopes to "cut regulations by 75 per cent, maybe more" and the rolling back of regulations protecting streams, consumers, and retirees, the story of Nader, the American automobile, and passenger safety is worth revisiting.

Long before he won 2.74 per cent of the popular vote during the 2000 US presidential election (and got branded as a 'spoiler' who gifted the election to George W Bush), Ralph Nader was a Harvard law student who spent his free time investigating automotive safety. Over the course of a decade-long investigation starting in the mid-50s, Nader became convinced that automakers were peddling a dangerous product. "For over half a century," his 1965 book began, "the automobile has brought death, injury and the most inestimable sorrow and deprivation to millions of people." He seemed to have a point, for at the time automobile crashes were the fourth largest cause of death in America behind heart disease, cancer, and stroke.

Even worse, Nader contended, automakers had known that their product was dangerous and had done nothing about it. The benefits of cheap yet effective safety innovations such as seat belts, collapsible steering columns, and padded dashboards were well-known within the industry, but American automakers had neglected to install them in their new models or even direct much money to investigate their effectiveness. Despite earning $1.7bn in profits in 1964, General Motors contributed only $1m to fund external automobile accident research. This led, in Nader's words, to a "gap between existing design and attainable safety".

Why had the industry ignored such moral imperatives to public safety? Because, argued Nader, automakers feared that drawing public attention to the need for safety improvements like collapsible steering columns (which prevent the driver from being impaled on the driveshaft during an accident) would cause people to view cars as unsafe and therefore drive down profits. Better to keep potential buyers focused on 45-inch tailfins and 400 horsepower engines. Accidents, and the injuries or deaths that resulted from them, could be passed off as the fault of the 'nut behind the wheel' rather than anything to do with the design of the car itself.

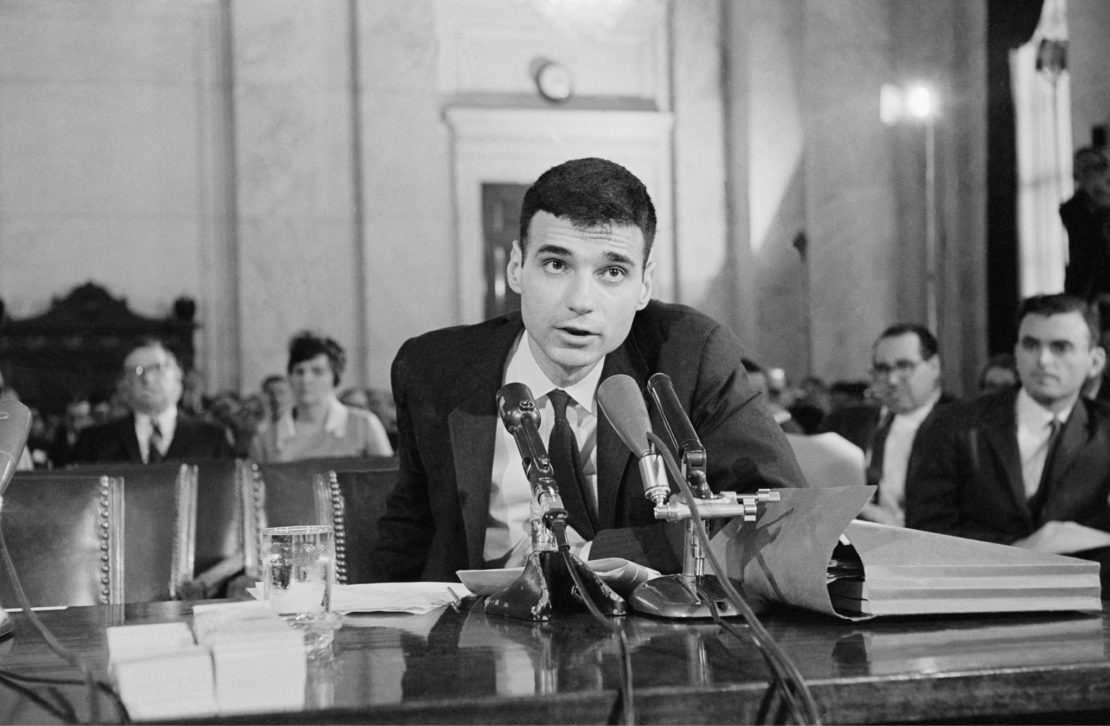

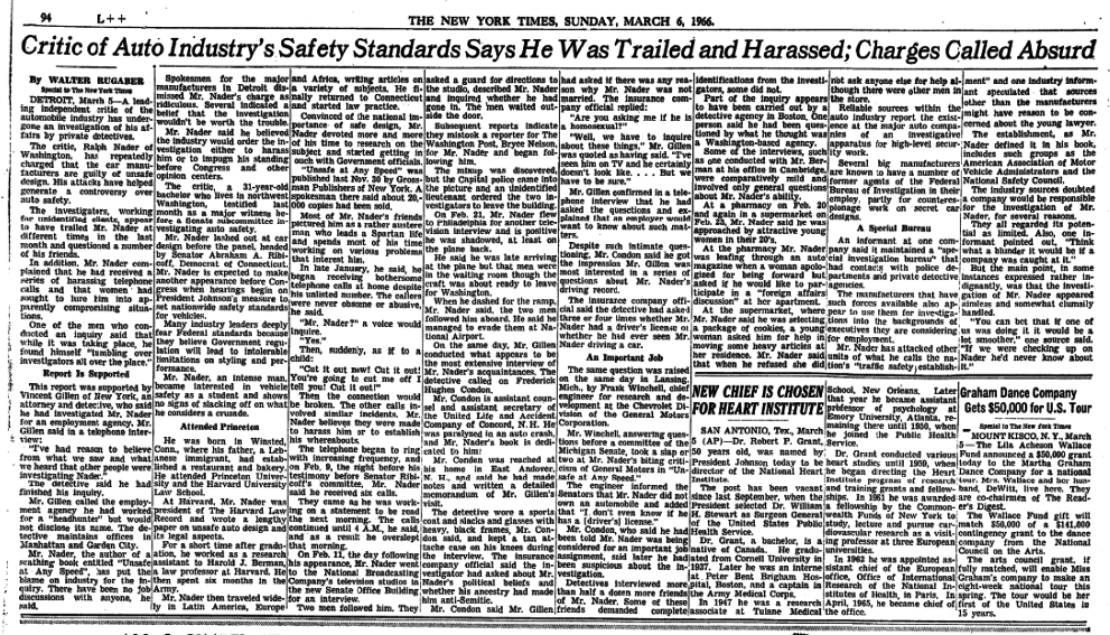

The book was an immediate sensation, and in 1966 Nader appeared before Congress to testify about unsafe practices in the automobile industry. His campaign seemed to gain credibility when it was revealed that General Motors had hired private investigators to dig up dirt on the young, unknown lawyer. In a March 1966 article, the New York Times offered a detailed account of the extent of the surveillance, including the allegation that General Motors had sent "attractive young women in their twenties" to try to catch Nader in a compromising position.

In one episode, the paper recounted, Nader had been leafing through an auto magazine at a local pharmacy when "a woman apologised for being forward but asked if he would like to participate in a 'foreign affairs discussion' at her apartment." This made great newspaper fodder, and led to the spectacle of the president of GM seeking to assure Congress that, despite the often deeply personal nature of the investigations, he had "no interest whatsoever" in knowing Mr Nader's political affiliations, religious beliefs, or sexual preference.

Automakers had known that their product was dangerous and had done nothing about it. Better to keep potential buyers focused on 45-inch tailfins and 400 horsepower engines

When the Senate Commerce Committee released its report soon after, it echoed many of Nader's findings, noting that it had found "disturbing evidence of the automobile industry's chronic subordination of safe design to promotional styling". The report led to the passage of numerous enhanced safety standards under the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act as well as the creation of a new agency, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, which had a remit to establish minimum safety standards for all automobiles and develop 'crashworthiness' design improvements.

Henry Ford II, eldest grandson of Henry Ford and then head of the Ford Motor Company responded curtly. "Many of the temporary standards are unreasonable, arbitrary, and technically unfeasible," he warned. "If we can't meet them when they are published we'll have to close down."

Despite these foreboding predictions, in the years since these safety measures were passed, the number of deaths from automobile accidents in the US has fallen from 5.50 per 100m vehicular miles travelled in 1966, to 3.34 in 1980. By 2015 that number was down to 1.12. Over that time, an estimated 613,000 lives have been saved. (A separate study puts the number at 3.5 million.)

A similar story played out in a number of other areas over the next decade as regulations were drawn up to protect workers, the environment, and public health. Nader, it seemed, had almost single-handedly helped convince the American public of the value of regulation.

By the early 1980s, however, public enthusiasm for regulation had begun to wane. A Louis Harris poll noted that while in 1976 roughly "as many consumers wanted more regulation as wanted less", by 1982 anti-regulation opinion outweighed pro-regulation opinion by a ratio of two to one.

How had this happened? According to two contemporary observers, regulation had developed "a public image problem". Writing in 1985 during the Reagan administration's campaign of deregulation, Joan Coalbrook (a former head of the NHTSA) and David Bollier argued that although social regulation was "demonstrably beneficial to human health and the environment", public conversations surrounding regulation no longer centred on the social value of regulation – eg the environmental and health benefits – but on those factors that regulated industries deemed most important – for example, cost, inconvenience and intrusiveness.

Nader had almost single handedly helped convince the American public of the value of regulation

The Reagan administration had, according to Coalbrook and Bollier, spun a "simplistic, quantitative cocoon" around the debate, thereby limiting what counted as valid evidence and controlling access to the debate itself. Ethical judgments about safety, health, and the environment – which are not easily expressed in economic terms (indeed, how does one quantify the social value of clean rivers and streams?) – were therefore restricted. Once ensconced in their quantitative cocoon, those campaigning for deregulation were able to reframe the debate away from the "most inestimable sorrow" detailed in Nader's book and focus instead on 'removing barriers to innovation' and 'cutting out burdensome regulations'. The 'regulation is bad' narrative became so ingrained that the last thing regulators and government officials wanted was to be seen passing new regulations or enforcing existing ones.

And so, in 2017, Trump is declaring his intention to mount a "historic effort to massively reduce job crushing regulations" and Nader is often remembered by deregulation campaigners as an "anti-business activist". But the assumption that self-regulation or the market alone can provide the same protections to consumers, commuters, and the environment is clearly unfounded, as the automobile example shows.

But cutting such regulations will likely still not produce the desired effect of increasing production and strengthening the economy, whatever The Donald thinks. When governments focus on designing regulations cooperatively with input from regulatory bodies, regulated industries, and the rest of society – rather than simply scrapping them – regulations can not only protect humans and the environment from the excesses of market-driven industries, but actually benefit those industries. By establishing clear, simple, and intuitive goals and incentives, such cooperatively designed strictures can help lessen the legal and reputational uncertainties that often go hand in hand with the process of developing new technologies, and can shift industry objectives so that business goals like profit are more closely aligned with social needs like health and safety. More, they can level the playing field among industry rivals (net neutrality being a good contemporary example) while creating new forms of market competition.

Explore

What lettuces tell us about deregulating Britain 'This house proposes that we nationalise Uber' Innovation heroes, #3: Geoffrey PykeThe automobile industry again serves as a case in point. In an interview with the New York Times, Robert A Lutz, a former top executive at Ford, Chrysler, and General Motors, admitted that while he does not like Nader and did not like Not Safe for Any Speed, NHTSA regulations had nonetheless proven beneficial by setting "ground rules where everybody has to do something and nobody has to worry" about finding themselves at a competitive disadvantage. More, despite the fact that many automakers railed against the imposition of safety regulations, those that managed to manufacture the safest cars were able to market themselves as such to consumers and distance themselves from their competitors.

A similar shift in attitudes to regulation has occurred in the UK automobile industry over the past 10-15 years – this time in relation to regulation that seeks to encourage energy efficient and low emission vehicles. As one automotive manufacturer put it in a 2014 report on 'Investing in the low carbon journey': "At the highest level, the creation of a level playing field [CO2 target] by the [European Commission] was extremely helpful. A clear long term target is what industry needs – it will find a way to respond." An executive from an automotive R&D services company explained the industry's change in mindset: "Back then, environmental regulation was seen as a threat not an opportunity."

In both instances, well-designed regulations had the effect of helping national industries innovate and remain competitive internationally. At a time when US automakers are attempting to develop innovative new technologies (driverless cars, electric ones) and again face competition from foreign automakers, Mr Trump would do well to stop thinking of regulations as a barrier to innovation and start thinking of them as a means to spur innovation.

Not only will commuters and the nation's rivers and streams thank him, he might even receive a few thank you notes from grateful industry execs as well.

And speaking of thank you notes, if you or anyone you love ever survives an auto accident, maybe send one to Nader as well. I'm sure he'd appreciate being remembered for something other than the 2000 US presidential election.