Remodel, reconstruct, renew

Sarah Burge has spent more than £1m on procedures to remodel her body. As a beauty consultant who runs a referral clinic for plastic surgery on Harley Street, she considers her own body a walking advertisement for her profession.

The work she has had done includes: having her face lasered every five years to remove a layer of skin (at cost of £32,000 so far); facial dermabrasions – the skin is effectively sanded every five years (£20,000); and gore-tex fillers threaded into the lines around her nose and mouth (£5,000). She has also had liposuction to her jaw twice a year for 25 years (£36,000); laser treatment on her teeth every five years (£18,000); and an “upper-eye lift”, where “excess” skin is cut from the lid, and the folds stitched together (£5,500).

“I consider myself now a work of art, an art form, almost like I’m an exhibit,” she tells me. Burge’s day job has, in part, allowed her to fulfil these desires: she lets plastic surgeons try out their skills on her body and if she’s happy with the result, she refers clients. She has also embraced media attention about her multiple treatments: a dangerous relationship that has seen her being paid to fly around the world, while also being publicly chastised. The American talk show host Anderson Cooper invited her on his show in 2012 only to dramatically throw her off it, with questionable spontaneity. She has been pilloried in the tabloids for spending thousands on her then eight-year-old daughter, throwing lavish makeover parties, entering her in beauty pageants and gifting her vouchers for plastic surgery that can be cashed in at 18. These stories, she says, were distorted: the vouchers were given to her by plastic surgeons in lieu of payment and work as bonds, ready to be sold, if her daughter wishes.

Nevertheless, she readily admits that although she felt close to suicide when the media campaign was at its height, she also ‘thrives on it all’, appearing on reality TV shows both in the UK and in Germany. Moreover, she accepts her Human Barbie nickname, coined by one newspaper, with something of a shrug.

Burge fits the image of a certain type of buxom blonde, but as a teenager she had different ideas of beauty. She remembers how, as a promising acting student at the Italia Conti Academy of Theatre Arts in London, “I wanted to become like Bette Davis, one of the unconventional Hollywood actresses of that time. She wasn’t a classic beauty, but she did possess something that was uniquely different that I was attracted to, so I thought I’d model myself on her,” she says. That ideal changed as her path was diverted: without her family realising, she was groomed as a prostitute at the age of 14 by a much older boyfriend, she left school without qualifications, found herself in abusive relationships, became a Playboy bunny and then, at the age of 29, had an affair with a man who attacked her, punching her in the face and cutting her. “I was stabbed and slashed with scissors,” she says. “He completely carved my face up like patchwork [until I] just looked like a monster.”

”I lost everything,” she says. “I lost my whole life as I knew it.” She hid herself away for years, she says, fantasising about being different. “I was constantly poking and prodding my face, thinking about going to sleep for hours and waking up with a new face. It was like my obsession.” The NHS had repaired her, but Burge wanted more. “I was told by the doctors I needed psychiatric help,” she says. “I didn’t need psychiatric help, I needed a surgeon.” This need, she says, was the key to her education. Seven years of nursing training later, she set up her own consulting rooms in Harley Street, advising people who wanted to change their appearance.

It’s easy to understand why somebody who had sustained such an attack would be desperate to look like they had before. Her novel, Fuck it Fear it, based on her life, deals with this rehabilitation: but Burge has gone much further than repairing her damaged face. She has had her vagina surgically remodelled – a ‘designer vagina’ – for £15,000. The buttock implants (£6,500) and liposcution to her stomach (£4,500) were not connected to the attack. She has had a breast reduction, which involved her nipples being removed, sewn back, flesh folded, and liposuction (totalling £12,000), as well as two surgeries for uplift (£14,500) and then an injectable uplift (£3,000). There were calf implants for shapelier legs (£11,000), buttock implants (£6,500), a tummy tuck (£9,500), and regular non-surgical procedures – including yearly Botox under her arms, monthly teeth-bleaching and fortnightly skin peels – that amounted to £22,000 a year.

Would she say she has an addiction to surgery? “Yes.” But, “I just wanted to become the person I was always meant to be,” she says. “The person I was always meant to be was an educated business woman with good looks, that’s it. That’s who I was meant to be and who I’ve made myself become.”

It would have been great material for a work of science fiction fifty years ago. Here’s a world where anything is possible. Don’t like your nose? Simple: get a new one. Wrinkles? Have a face- lift. Thighs chunky? There’s a machine that will suck the fat away. Face thin? There’s a machine to put that fat in your cheeks instead. Breasts too small or too large? Adjust size to order. Can’t walk? Buy a robot suit. We are in an age where it is possible to remake ourselves. Provided you can pay for it, you can pretty much get a whole new body if the original one isn't functioning or you simply don’t like it.

Last year, in pursuit of something better, over 50,000 people in the UK had cosmetic plastic surgery. That’s an increase of 16.5 per cent on the year before. Among the most popular were breast augmentation, blepharoplasty (eyelid surgery) and fat transfer (when ‘excess’ fat is transferred from one part of the body to another). People are remaking themselves because they can. And to look like what? A little closer to what is considered perfect, maybe. Yet the word perfection is used so often the meaning has become dulled, the corners rubbed off; instead, it’s a signifier for something, an achy sense that it’s what other people have. Who says that symmetry and high cheekbones are the ideal? And who really fits that bill? A tiny proportion of the population, invariably those on catwalks, or those who stare out at us from cinema screens and magazines (and who may or may not have had surgery themselves); spheres in which a certain amount of artifice is expected.

Dr Christopher Hilton, Consultant Psychiatrist in West London Mental Health NHS Trust and Senior Clinical Lecturer at Imperial College London, says he has met many patients whose sense of themselves emotionally and physically has led them to pursue behaviours which seem extreme to others. Without commenting on any particular cases, he explains, “Some want to change or 'improve' their appearance through cosmetic surgery… I meet patients who say they're unable not to restrict their diet to the point of starvation or exercise to dangerous excess. One patient feared that there was something wrong with her face, visible to everyone, and requiring her to spend hours checking and reapplying cosmetics to hide the – to me – imperceptible blemish.”

“I gather there’s quite a bit of evidence that the majority of patients are satisfied with the results of cosmetic surgery,” Hilton continues. “However there are also various reports that individuals whose appearance is changed significantly by disfigurement, surgery or whole face transplantation, may suffer bereavement and a sense that it is more challenging to convey a real sense of themselves. For some, of course, having this ‘mask’ may be exactly what they were hoping for.”

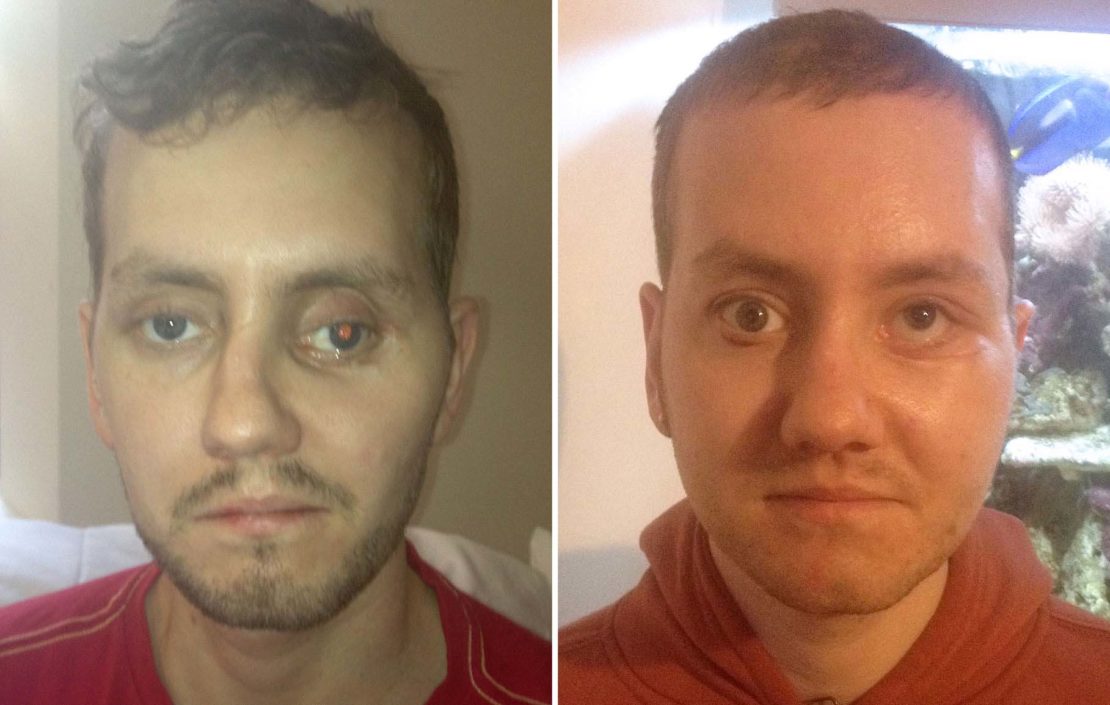

For Stephen Power, who had a serious motorbike accident in 2012, the challenge was how to live a normal life when survival meant disfigurement. The crash fractured his skull, broke both cheekbones, his top jaw and his nose, even though he had been wearing a helmet. The 27–year-old emerged from hospital four months later with his life, but not the face he knew. He hid away and was rarely seen in public without a hat and sunglasses. Had he not existed in an age of pioneering surgery, this could have been the end of the medical intervention. The Cardiff man was blessed in one respect though: 3D printing is no longer just a fun idea, it’s a medical fact. The UK is one of the countries forging ahead with advanced technologies, with research teams in Newcastle and London.

Power’s case was undertaken by CARTIS (The Centre for Applied Reconstructive Technologies in Surgery), a collaboration between the National Centre for Product Design and Development Research at Cardiff Metropolitan University, and Morriston Hospital’s Maxillofacial Unit. Using CT scans to print a symmetrical 3D model of Power’s skull, along with plates, screws and cutting guides, the surgeons had precision tools for surgery. In March this year, they operated on Power for eight hours: one of the first trauma patients to undergo this type of surgery, he now has a face that is as close as possible to his original one.

he result was, he told the BBC, completely life-changing and reversed his need to hide away. Adrian Sugar, the maxillofacial surgeon who helped reconstruct his face, told the press: “Stephen had a very complex injury and correcting it involved bones having to be recut into several fragments. Being able to do that and to put them back in the right position was a complex, three-dimensional exercise. It made sense to plan it in three dimensions and that is why 3D printing came in; and successive 3D printing, as at every different stage we had a model.”

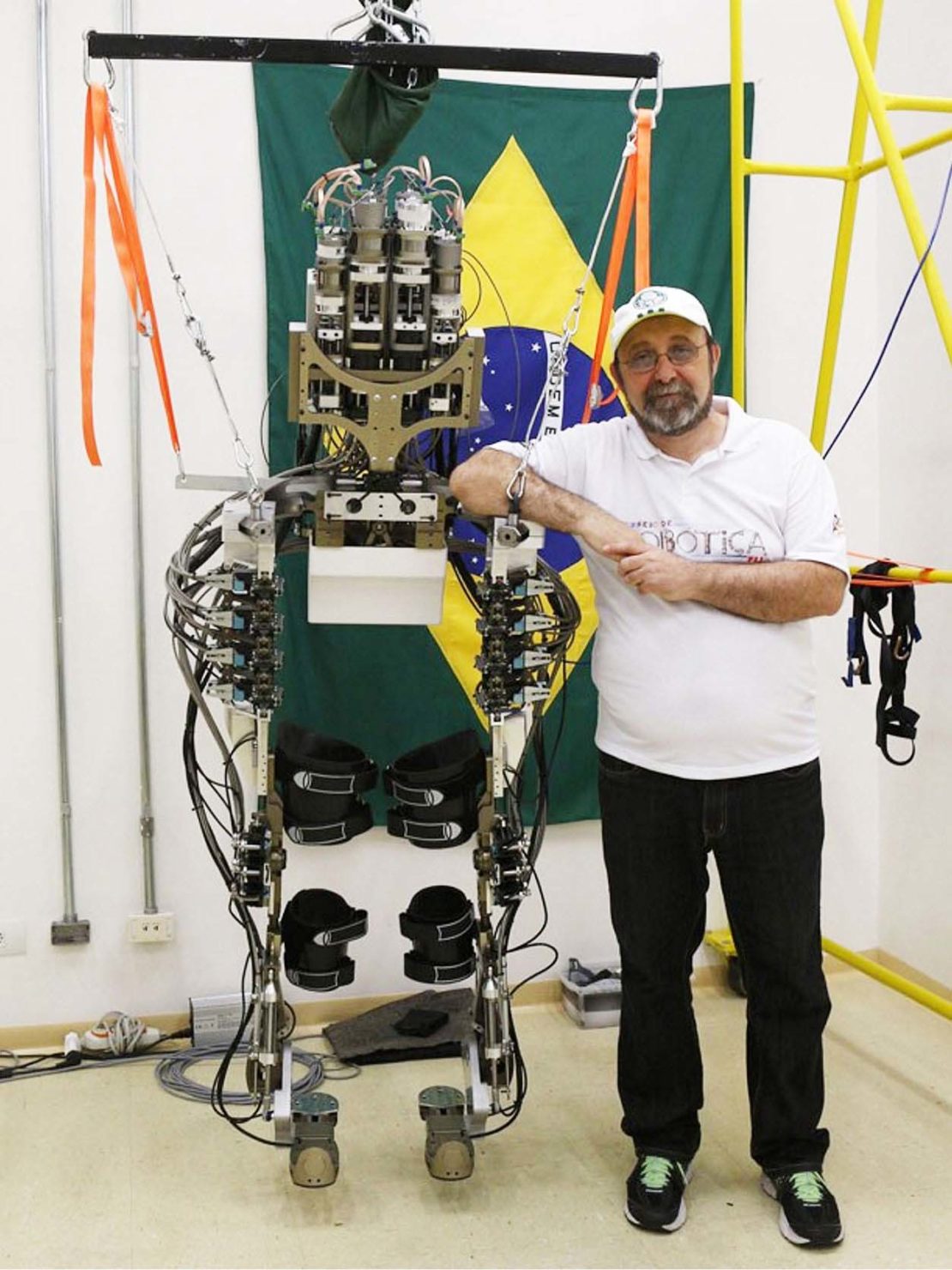

Advances like this feel like arrows into the future, glimpses of a different perspective on the human body. In this light, nothing could be more symbolic than the first kick of this year’s World Cup, taken by Juliano Pinto, a paraplegic man, wearing an exoskeleton. The cap he wore on his head communicated brain signals to a computer in the robotic suit’s backpack that commanded the legs to move, which they did by hydraulics. He kicked the ball.

The suit was created as part of the Walk Again Project: a consortium of scientists working together under the leadership of Dr Miguel Nicolelis, a Brazilian neuroscientist and pioneer in the study of brain-machine interfacing at Duke University in the US. In a statement, the group said it heralded a future “in which people with paralysis may abandon the wheelchair and literally walk again”.

One person who is committed to this ideal is Professor Dr Robert Riener from the University of Zurich, event organiser of the 2016 Cybathlon. In the first championship for robot-assisted athletes, the audience will watch para-athletes using powered exoskeletons, competing with electrically stimulated muscles, brain-computer interfaces, and the very latest powered knee and arm prostheses. It will be held in Zurich, organised by a coalition of Swiss robotics labs. Switzerland, Riener says, is increasingly known as the ‘silicon valley of robotics’, so substantial is its number of research facilities. “What’s going on now is a merging of robotics and neuroscience,” he explains. He hopes the Cybathlon will raise the profile of breakthrough technologies, taking them a step closer to being prolific in everyday life. “Research [and science] are important to disseminate and to present to the public,” he says. “I know from my work that assisted devices for paralysed people are still not accepted.”

That seems surprisingly narrow-minded of able-bodied people, until you imagine someone walking down the street in a robotics suit: it’s too new to be normal, for now. And when remaking the body is this drastic, some groundwork has to be laid. “With organising the Cybathlon,” Riener continues, “we want to push the industry to develop assisted devices which are really functional and which help people to improve mobility and gait and function in daily life.”

If the aim is to move from theory to practice as fast as possible, it makes sense that there are two prizes for each event: one for the athlete – the ‘pilot’ – driving the device, and the other for the company who built it. How long does Professor Riener think it will take for paralysed people to be able to use exoskeletons practicably (they are already available to buy)? “They are still bulky and slow,” he says, “and battery power is limited… so it might take another four or eight years maybe – quite long – until they are being a real support to patients.”

At the Kentucky Spinal Cord Research Center at the University of Louisville, Dr Claudia Angeli and collaborators have reported in a groundbreaking study that ‘zapping’ the spinal cords of paralysed patients has enabled them to move. Patients have wiggled their toes for the first time, and even briefly stood up. “We still have a lot to learn about the mechanisms, but we know that the spinal cord is very smart and has a lot of potential even after injury,” says Angeli, the lead author on the study.

It’s a complex procedure, where a 16-electrode array is implanted on top of the spinal cord, connected to a stimulation unit implanted in the participant’s abdomen. Through a wireless controller, the research team select which of the 16 electrodes are active, if they have a positive or negative charge, and what frequency and voltage stimulation to use. This raises what they call the ‘excitability’ of the spinal cord, which then becomes more receptive to other signals and information that might generate a movement. Angeli explains that two of the four participants have impaired sensation on their legs. Even so, “they can feel a tingling feeling on their legs,” she says. “All four describe it as their legs becoming alive and just feeling like they can connect to them.”

What has been most memorable about this revolutionary work? The first participant, she says, moved seven months after the implant, which was a great cause for celebration. The researchers thought this was a template for the length of time the process would take. But the second participant managed to move the first time he was asked. “This was very unexpected,” Angeli says. “I think what made it a little more special was that his mom was in the lab at the time, and her reaction and the hope that brought to her was extremely rewarding to the team.”

Their work offers some hope that such impaired bodies could one day rediscover their function. As a result, the team currently have a database of over 2,500 people who are interested in participating in their research. In the face of this, Angeli is cautious but optimistic. Might the work mean that one day paralysed people could walk again? “I think that is a possibility,” she says. “However, we have a lot of work ahead of us before we can know for sure.”

They are currently working to improve the technology, developing a stimulator that has more flexibility and features which allow them to continue testing and improving how we function during stepping. “Ultimately, we would like to see this become a clinical intervention,” she says. At the moment, a great deal depends on funding: each patient is with the team for almost two years, training in the laboratory five days a week, and that takes resources.

The money and time that has to be poured into such endeavours seems daunting, yet it is incredible to think that in the coming years paralysed people could be ‘zapped’ or use robotic suits to help them walk. But then, leaps of science and technology often seem to dwell in the realm of the imagination, until they make it into our daily lives.

This is the thinking of Cambridge researcher Aubrey de Grey. Like Sarah Burge, he’s fighting ageing – but from the inside out. A molecular biologist, de Grey is also a gerontologist and co-founder of the SENS (Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence) Research Foundation, a non-profit organisation in the US. SENS is devoted to researching age-related disease, and the regenerative medicine that could cure it.

His TED talk, which argued that ageing is a curable disease, has had over 2 million hits, and it’s not hard to see why: the idea he proposes is that certain types of cellular decay which eventually lead to death could be combated. In theory, this means some humans could live for 1,000 years, although that is not his goal; he says the research and treatment is about health, and could save around 100,000 lives a day. People could be as physically healthy at 90 as they are at 30, he argues.

This kind of far-thinking research is always fun to ponder, as it throws up so many questions: how long do we want to live? How would society change? What would the psychological consequences be? Though even if de Grey turns out to be right, these are problems this generation is unlikely to have to address. Butwe are in an age where things are possible; and where they are not possible now, there are people who want to make it so in the future.

In this environment, our bodies are something of a final frontier. Perhaps it is because many of us dwell partially in a digital world that we can feel a certain freedom in altering ourselves in a way that previous generations could not. We move effortlessly between the virtual and physical, dissolving ourselves into images only to remake that image somewhere else, in real time. Yet our bodies, the flesh and blood, our corporeal selves, are still as fragile as the theories are robust. Regardless of whether or not we should embrace it, the ability to mould and change who we are, or appear to be, is there for the taking.